1. Introduction

Empirical research on the experience of absorption during reading has increased over the last decades, but the field also suffers from one important lack, being qualitative data on the nature and frequency of occurrence of absorption in daily life. Absorption has mostly been investigated in lab settings, and because it is an experience that is hard to reproduce in a lab, we cannot be sure to what extent the data gathered during experiments is related to how people experience absorption in everyday settings. Because readers often use the term ‘absorption’ (and related terms such as ‘immersion’, ‘flow’, ‘transportation’, and ‘engagement’) as a positive appraisal of a book (as shown in the studies of Kuijpers, Absorbing Stories. The Effects of Textual Devices on Absorption and Evaluative Responses), the book reviews posted on the website Goodreads are full of descriptions of unprompted daily-life absorbing reading experiences. Goodreads has collected approximately 3.5 billion book reviews written by 125 million users (Goodreads) – a figure that grows every day. It therefore holds a vast amount of potentially valuable qualitative data that we can use to investigate absorption and other reading experiences.

By using the Story World Absorption Scale (SWAS; Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption”) – a self-report instrument developed in the field of empirical literary studies to capture absorption during reading – as the basis for an annotation scheme with which a sub-set of reviews on Goodreads are annotated for mentions of absorption, this paper tries to achieve two main aims. First, it tries to ‘validate’ the SWAS by comparing statements from the instrument to sentences in unprompted reader testimonials found on Goodreads. Through this comparison, we address the question of whether readers in their online evaluations of books talk about absorption in similar ways researchers do when we investigate this experience in experimental settings. Second, it discusses the merits and limitations of manual annotation of unprompted reader testimonials as a method for validating self-report instruments.

This paper is but one of the outcomes of a larger project that also aimed to produce the first manually annotated, machine-readable corpus of online book reviews, and teach a machine-learning algorithm to detect absorption in book reviews on a large scale. These aims have partially informed the pragmatic approach we have taken to the annotation process, and where this is appropriate these instances will be pointed out in this paper. However, as the corpus and the annotation guidelines we developed are published elsewhere (Kuijpers, Lendvai, et al., “Absorption in Online Reviews of Books: Presenting the English-Language AbsORB Metadata Corpus and Annotation Guidelines”), and the machine-learning part of the project is still in progress, this paper mainly focuses on the annotation process and is structured as follows.

First, we will review the Story World Absorption Scale and its use in empirical literary studies. We will examine its different dimensions, their items and their applicability for annotating online book reviews. This will allow us to identify potential differences and similarities between studying absorption in the lab and using unprompted reader testimonials. Second, we will introduce the annotation task we developed for the purposes of this project. Third, we will describe the annotation process and the iterative improvement of this process with the help of inter-annotator agreement studies. Fourth, we will describe the curation process and talk briefly about the creation of the annotation guidelines for the purposes of open access sharing with other researchers. Finally, we will discuss how this annotation process has informed the validation and subsequent reconceptualization of the Story World Absorption Scale and the potential implications for the use of this instrument in further experimental research.

2. Story World Absorption

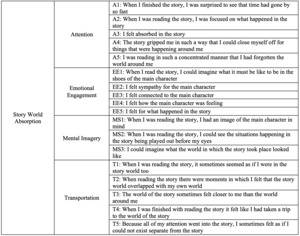

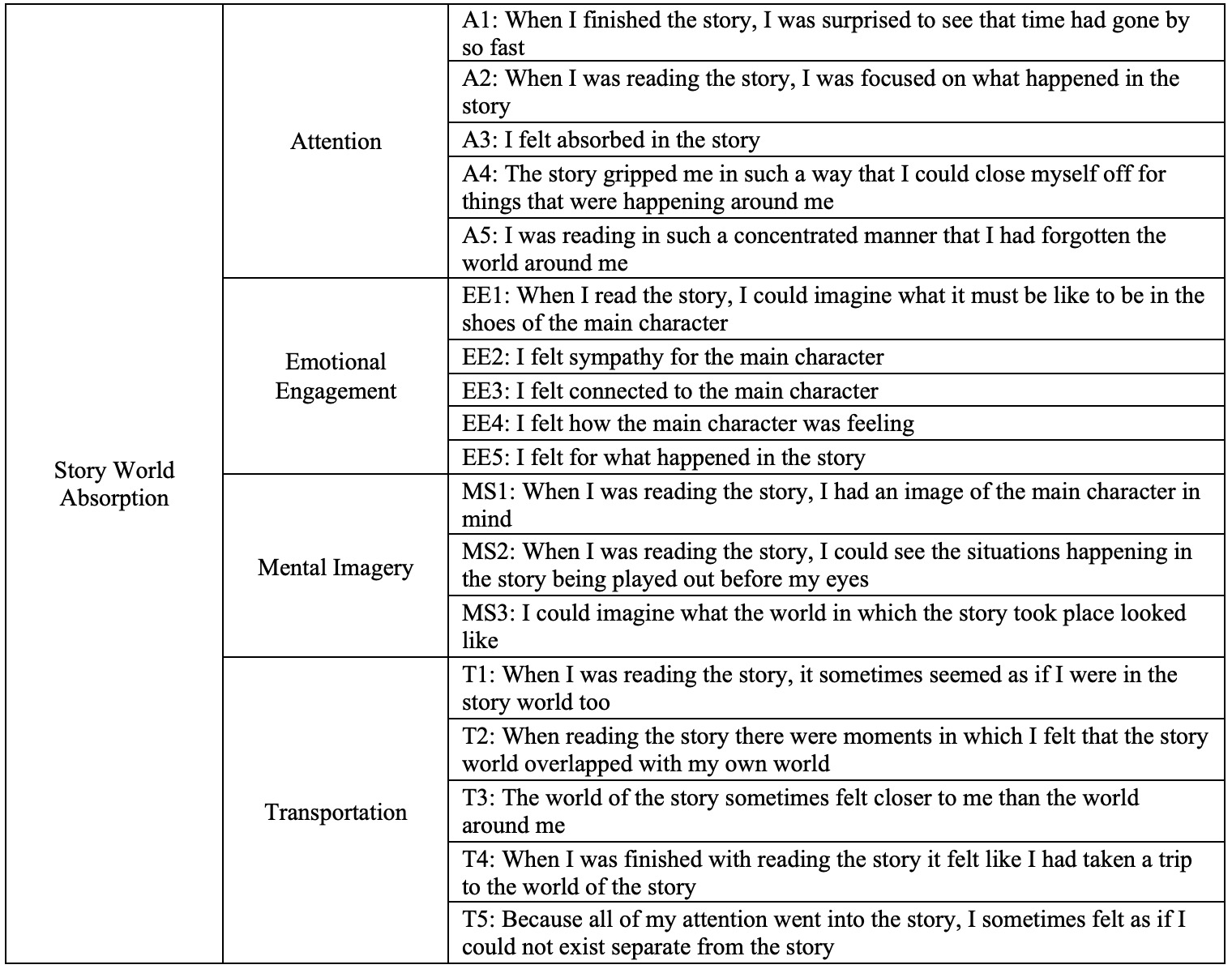

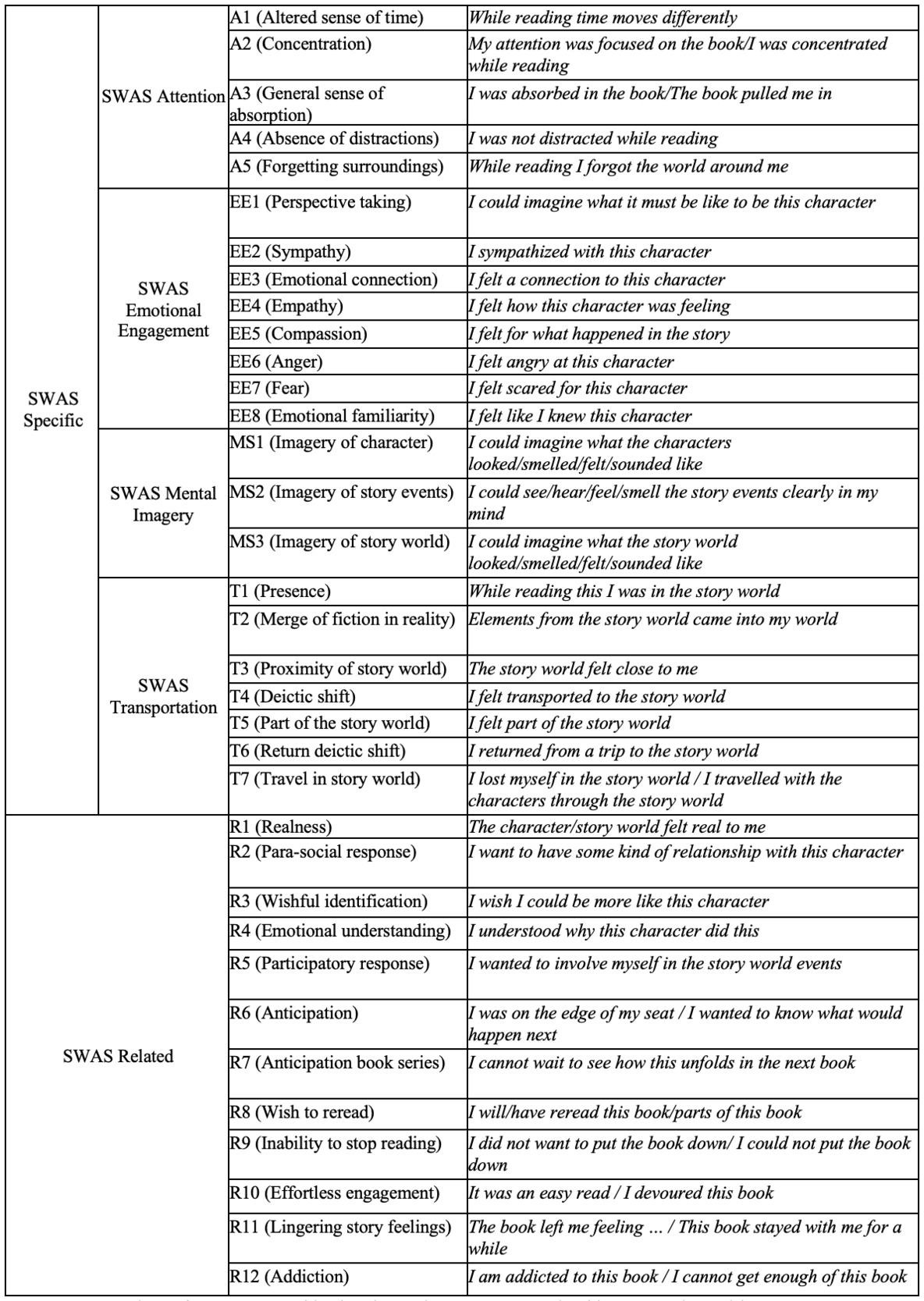

The Story World Absorption Scale (SWAS) was originally developed to capture reading experiences in which the reader feels lost in a book, fully submerged in its story and emotionally and imaginatively involved (Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption”). Absorption is usually experienced as effortless and enjoyable by readers and participants in several studies have commented on feeling powerless to stop the pull of a book in cases when they felt absorbed (cf. Bálint and Tan; Bálint et al.; Green et al.; Nuttall and Harrison). Even though there were available self-report instruments that captured similar experiences at the time, the authors felt the need to develop a new instrument that specifically targeted absorption in textual material. Their aim was to develop a multi-dimensional instrument that was sensitive to different textual narrative stimulus materials and able to predict various evaluative outcomes (i.e., enjoyment and appreciation). The SWAS was developed and validated over a series of studies (see Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption” for full details) and ended up containing 18 statements divided over four dimensions (see Figure 1). These four dimensions are rooted in theoretical and empirical work on narrative absorption and reflect the most commonly mentioned aspects of absorbing reading experiences, namely Attention, Emotional Engagement, Mental Imagery and Transportation (deictic shift) (Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption”).

The scale is currently available in at least three different languages (Dutch, English and German, accessible on Open Science Framework; Kuijpers et al., Story World Absorption Scale), it has been used in experiments as well as surveys and has shown great reliability across all of these contexts. Additional psychometric work has been conducted to investigate the relationships between the four dimensions on the SWAS, which resulted in the conclusion that Attention seems to be a precondition for the other three dimensions to occur (Kuijpers, “Exploring the Dimensional Relationships of Story World Absorption: A Commentary on the Role of Attention during Absorbed Reading”). For the annotation work at the core of the present study, we decided to take the SWAS as our starting tag set (see Figure 1 for the full set of items included).

2.1. Absorption in online book reviews

We decided to first do some preliminary, exploratory investigation of the general language use on Goodreads, to decide whether we needed to expand or adapt the starting tag set in any way. When taking a cursory look at the reviews available on Goodreads, it became apparent that absorption is clearly an experience and a term that a lot of reviewers seem familiar with. However, a couple of differences between absorption expressions on the SWAS and in the online reviews immediately were judged likely to influence the annotation work ahead. One such difference was that people on Goodreads review entire books and often discuss series or entire oeuvres, whereas the SWAS has up till now only been used to investigate reading of short stories or excerpts from novels. Thus, expressions concerning anticipation of future story events (even events outside of the novel, such as in a sequel or series) clearly indicated absorption but were not reflected in the SWAS. To account for these instances, we had to create an additional tag and add it to the tag set. Throughout two practice rounds of annotation, we added ten new statements to the tag set in total. Whenever we encountered phrases that we felt illustrated an aspect of absorption that was not captured by any of the tags available and that was used often enough by different reviewers, we came up with an example statement to add to the tag set. Examples of absorption statements we encountered a lot but were not reflected in the SWAS at all, were ‘lingering story feelings’ (“It is one of those stories that just sticks with you”) and ‘addiction’ (“I could not get enough of their storyline”). The statements we added to refine and expand on the original, existing SWAS dimensions included, for example, negatively valenced emotional engagement such as anger and fear (“During her chase, I became afraid for her”) or a variation of mental imagery that focuses on the authenticity of the characters and story world portrayed (“These characters are just as real to me as individuals I know in real life.”).

A second difference was the language used in the reviews, which tended to be a lot simpler than some of the statements on the SWAS, due to the informal style of communication of most of the reviews. To accommodate for this difference, we split some of the longer statements into smaller segments and adapted the language to create more similarity to the language used on Goodreads. For example, we changed the original A5 statement “I was reading in such a concentrated manner that I had forgotten the world around me” by splitting it into two statements, namely A2 “My attention was focused on the book” and A5 “While reading I forgot the world around me”.

We also noticed that some theoretical aspects of absorption, such as effortless engagement and inability to stop reading (cf. Bálint et al.), were not reflected on the SWAS, but were mentioned often by reviewers. Thus, we expanded the tag set by adding seven statements based on an absorption inventory created by Bálint et al. in an interview study focused on absorption in reading literature and viewing films. This study was undertaken a couple of years after the SWAS was originally developed and thus the categories developed by Bálint and colleagues were not reflected in the original SWAS statements.

Additionally, some of the original statements were difficult to match to sentences in reader reviews, even after adapting them to much simpler language. There may be several reasons for this. First, the SWAS may tap into experiences that seemed important theoretically speaking, but that actual readers rarely experience (e.g., T3: “The story world felt close to me”). Second, the context of the online review community might affect what people talk about. Items A2 (“My attention was focused on the book”) and A4 (“I was not distracted during reading”) are important in experimental settings as evidence that absorption actually took place. In reviews, however, we found that people did not tend to talk about concentration and (lack of) distractions. This may be because, generally speaking, people will try to find a distraction-free space and time to do their leisure reading, or because this is not a common theme to write about in reviews, where the emphasis is on description of plot and evaluation of the text. Even though we did not find any matches for some of the original statements in our precursory investigation of Goodreads, we still decided to leave them in our tag set in case matches were found later, when reviews from different genres were used.

3. The annotation task

At the time when we started this project in December 2018 there were no annotation studies published with either a similar corpus or a similar abstract annotation task. In other words, we were unable to model our annotation task or the creation of our annotation guidelines to existing similar projects. This meant that we had to take quite a pragmatic approach to the creation of the task and the development of the annotation process. This approach was based partly on our intent to use the final annotated corpus for machine-learning purposes, and partly on our wish to develop annotation guidelines that could be useable for other researchers beyond the limits of our project. What resulted was an iterative process of improving the annotation task over the successive rounds of annotation in collaboration with our annotators.

3.1. Instructions for the annotators

The tag set the annotators worked with is shown in Figure 2, and was divided up into two main categories: SWAS-Specific (referring to the original 18 statements of the SWAS, divided over the four dimensions of Attention, Emotional Engagement, Mental Imagery, and Transportation) and SWAS-Related, which were the statements we added ourselves based on the absorption inventory from Bálint et al. or based on the annotation process itself. In addition to specifying which of the statements in this tag set a certain unit is related to, the annotators also had to specify when reviewers explicitly mentioned or signaled a lack/negation of absorption (e.g., "I struggled to get through a lot of the pages’’ or “None of the characters really mattered to me”), to make these distinct from expressions indicating the presence of absorption. We chose to add this option, as negation examples of tags are still very useful for a machine learning algorithm in helping to decide what is and what is not absorption. Including the negated SWAS-Specific and SWAS-Related tags, the total tag set now counted 72 tags. We also included the option to tag for SWAS-Mention, which was a higher-order category that specified non-specific examples of a tag, meaning statements that refer to general reading behavior (e.g., "I tend to get absorbed into stories with rich character descriptions’') rather than an appraisal of the specific book that is being reviewed (e.g., "I was absorbed in this book because it included rich character descriptions’'). When the annotators selected SWAS-Mention, they still had to specify whether absorption was Present or Negated and which specific tag was mentioned by the reviewer, and thus the final tag set counted 144 tags.

3.2. Annotation tools

We worked with two different annotation tools throughout the project. The practice rounds and the first four actual rounds were done using Brat (Stenetorp et al.) and from round seven we switched to INCEpTION (Klie et al.). We decided to change annotation tools because INCEpTION makes curation of the annotation work much easier. The practice rounds in Brat were curated, by the first author of this paper, in a separate .csv file, mainly to function as feedback for the annotators who were still learning about absorption and getting to know the natural language use on Goodreads. After the first six rounds, we set up an annotation system in INCEpTION in which the annotators had to navigate different layers. This structure and the names of these layers were based on the discussion during the practice rounds and was one that the annotators were comfortable with. First, they had to indicate whether reviewers mentioned an instance of absorption specific to the book that was reviewed (SWAS) or an instance of general absorption (SWAS-Mention). Second, they had to specify whether a presence of absorption (SWAS-POS) was established by the reviewer or rather a negation (SWAS-NEG) of absorption. Third, they had to decide whether a reviewer was mentioning one of the original SWAS categories (SWAS-Specific) or one of the related absorption categories we added during the practice rounds (SWAS-Related). And last, they had to pick the specific tag in either the SWAS-Specific or the SWAS-Related layers that matched the chosen review text segment best.

3.3. General annotation rules

The main criterion for assigning a tag was semantic or conceptual similarity between the statements in the tag set and a text segment. Semantic similarity refers to a match between the words of a statement in the tag set with words found in a review, whereas conceptual similarity comprises review text that describes conceptually the same thing as a statement in the tag set, but uses different words. For example, the category EE9 (Wishful Identification) is described by the example statement: I wish I could be more like this character. A semantic match we found read “wish I could be more like her”, whereas a conceptual match read “I want to be as ambitious as Adam and live a life like Gansey with the happiness of Blue”. As this example illustrates, we needed to allow for conceptual similarity, as reviewers often use the character names when expressing their feelings for or with them.

Each annotator freely established the boundaries of a relevant text segment, as long as the text segment included a complete clause, meaning it needed to include a subject, object and verb. If punctuation marks were used, they were to be included as well. The annotators were allowed to assign more than one tag to the same text segment, but only if they felt one unit expressed different categories at the same time (e.g., when a unit contains multiple clauses).

If the text segment expressed absorption on the part of the reviewer it had to be tagged, whether or not they used “I” as the subject of their sentence. Sentences like “It is that kind of engaging story that makes you keep reading and forget the rest of the world for a few hours” or “this one is a real page-turner, and one with enough twists and reveals that will keep the reader on her toes right up to the very last page” use “you” or “the reader” as subject, but are still considered to express absorption on the part of the reviewer. For more detailed information on the annotation rules, see the Annotation guidelines (Kuijpers, Lendvai, et al., “Absorption in Online Reviews of Books: Presenting the English-Language AbsORB Metadata Corpus and Annotation Guidelines”).

4. The annotation process

The annotation process started in March 2019 and was divided into 15 rounds (the first two of which were practice rounds in which we consolidated our tag set), the last of which was completed in October 2020. We chose to work with five annotators, because the experience of absorption is such a complex, abstract and multi-faceted phenomenon that it would pay off to discuss our annotation work with a larger group. Additionally, if it turned out that one or more of the annotators had trouble with the annotation task, we could continue with the annotations of just three or four of the annotators for our inter-annotator agreement studies. Moreover, inter-annotator agreement between five (or even four or three) annotators would provide a much more reliable benchmark corpus than if there were only two annotators involved.

4.1. Training and practice rounds

We started the annotation process with a workshop on absorption for which we invited experts on the topic to talk about absorption conceptualizations. During this workshop we looked at a handful of pre-selected reviews from Goodreads together with the annotators and the absorption experts, which facilitated an exchange that was quite useful as this was the first introduction to the topic for the annotators. During and after the workshop we realized that we needed to remain in contact with absorption experts who were native English speakers for input on and interpretation of certain expressions. During the practice rounds that followed we curated a list of inquiries to our English-speaking absorption experts, on which they provided us with helpful feedback, which have been incorporated in the annotation guidelines where applicable.

After the workshop, we started with two practice rounds of annotation. Over the course of these practice rounds we came together once a week to discuss the annotations, especially those cases where annotators were unsure about specific categories or designated phrases in reviews as “candidate undecided”. This designation was there so annotators could flag phrases that they thought were showcasing absorption without there being a match with any of the tags in our tag set. Based on these discussions, we refined the tag set, added categories (as described above) and simplified the language of the original statements. In other words, during the practice rounds we went from 18 tags to 35 tags (with the added layers described above, the total number of tags was 140). Discussing cases of absorption in the Goodreads reviews with a group of annotators has been beneficial to their understanding of the concept of absorption and to the inter-annotator agreement between them.

4.2. Iterative annotation improvement through inter-annotator agreement studies

After the practice rounds, the five trained annotators worked through 50 to 200 reviews every round (for a total of 13 rounds). The round lengths were determined by a trial-and-error process, throughout which we kept checking in with the annotators to see what the perfect number of reviews to be annotated was per month (which was about how long each round lasted). During each of our meetings, after a round of annotation, we came together and looked at the inter-annotator agreement (IAA) scores between the annotators. This helped us determine which categories were difficult to understand, and therefore had to undergo some adaptations in our tag set. It also helped us determine whether specific annotators had difficulties keeping up with the others. We had open conversations about these difficulties and adjusted our annotation process, tag set and guidelines accordingly.

In certain rounds we saw inter-annotator agreement drop, and we realized that after a certain number of reviews fatigue set in and the IAA scores suffered, and so the round length was adjusted. Other times inter-annotator agreement dropped as the annotators encountered reviews from a different genre. Different genres of books on Goodreads attract different communities of readers, which sometimes are accompanied by different review styles.

One additional, external factor that influenced the IAA scores and therefore the planning of our annotation rounds, was the Covid pandemic, which happened in the middle of the project, and to which we had to adapt in terms of number of reviews suitable for annotation and in terms of our monthly meeting schedule which now had to happen online. This was also the main reason for “merging” some annotation rounds, with which we mean that we had originally planned to meet after round 8, for example, but were unable to find a time to meet, and decided to extend the annotation time to include round 9 (the same is true for rounds 5 and 6 and rounds 13 and 14).

Finally, one of the annotators left the project after the fourteenth annotation round. As this annotator had shown a low agreement with the rest of the annotator team over the course of the project, we decided to, for the purpose of consistency, only present here the IAA results of the other four annotators throughout the project. Passonneau et al. showed that identifying and selecting subsets of annotators with relatively high IAA leads to better scores.

Throughout the annotation process, whenever we considered IAA scores, we looked at scores for the higher-order categories and dimensions, rather than the fine-grained tags. In the tag set shown in Figure 2, we focused on the two higher-order categories (SWAS-Specific and SWAS-Related) and the four dimensions of the SWAS-Specific category (Attention, Emotional Engagement, Mental Imagery, and Transportation) respectively. This decision was motivated by the rare occurrence of some of the fine-grained tags, which made it difficult to identify clear patterns and trends. We chose to express IAA using two coefficients: Krippendorff’s alpha and Cohen’s kappa, calculated on a sentence basis (based on sentence tokenization by Spacy, see Lendvai et al. for more information). As Artstein and Poesio point out, “deciding what counts as an adequate level of agreement for a specific purpose is still little more than a black art”. Our annotation task is particularly challenging due to several factors, which include the complexity of the tag set and the abstract nature of the concept to annotate for. We therefore do not expect to see IAA scores comparable to those reported in other computational linguistics papers, where the tasks are usually much simpler. We decided to go with a sentence-based approach to inter-annotator agreement calculation for several reasons. While classical emotion detection on written texts is typically applied on larger units of texts, such as entire reviews, this would be a unit too coarse-grained for our purposes. A sentence is a syntactically complete unit that is well distinguishable by preprocessing tools such as sentence splitters. Neural classification models, particularly BERT (Devlin et al.), which we applied to these data (see Lendvai et al.) lend themselves well to take the representation of entire sentences by means of the single aggregate CLS (classification) token, rather than of individual tokens, which would be too fine-grained for our purposes. For the machine learning tasks further along in this same project, this was the most pragmatic choice.

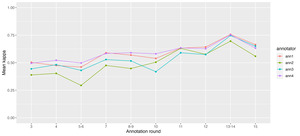

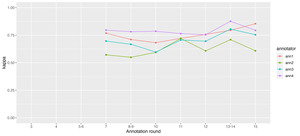

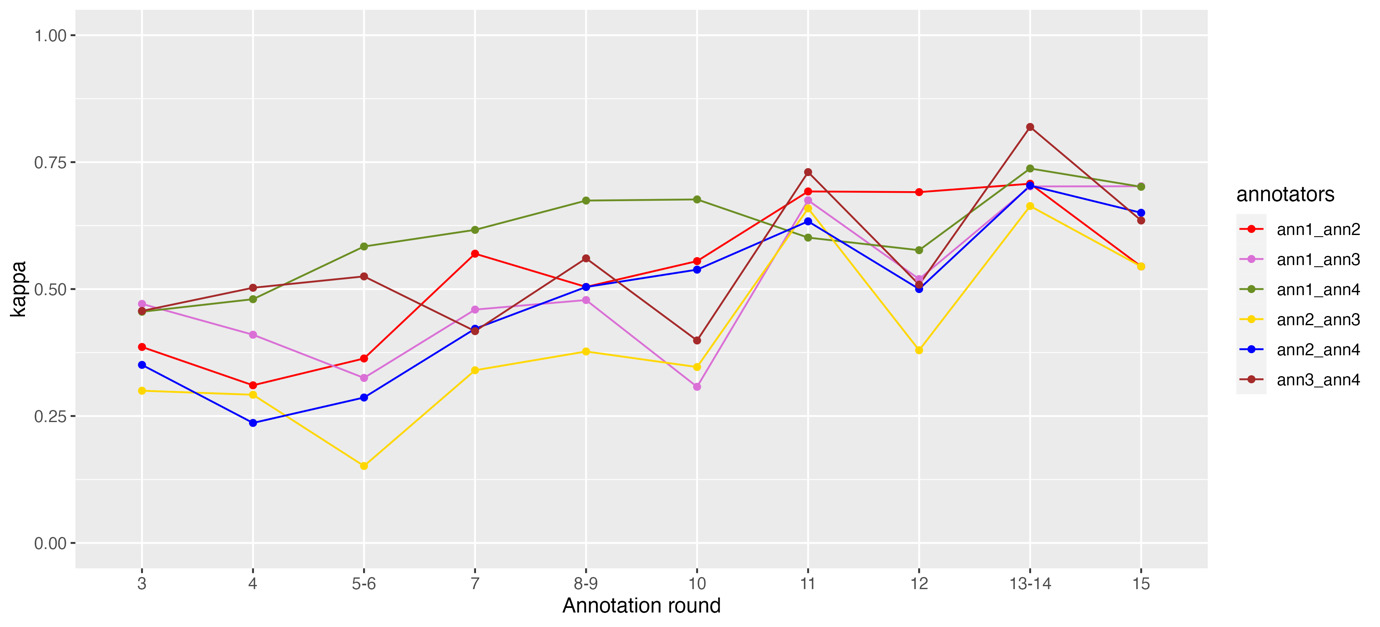

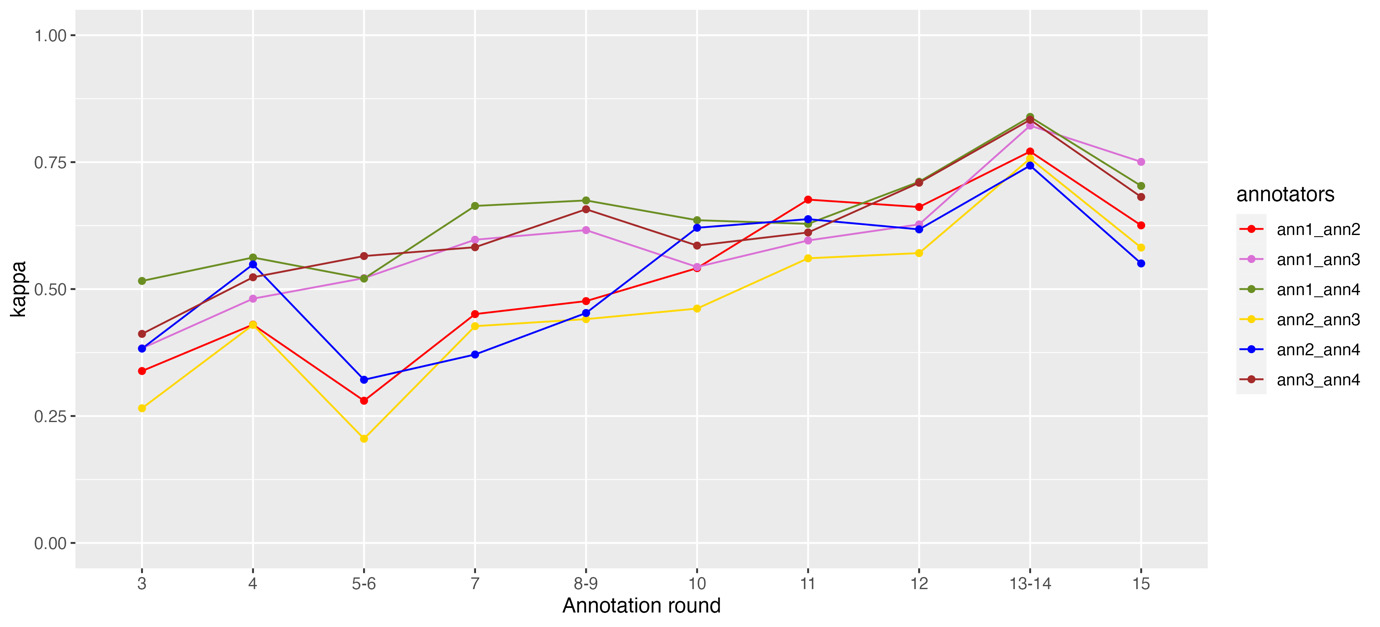

In Figure 3 and 4 we report IAA scores (Cohen’s kappa) for pairs of annotators and categories of absorption (SWAS-Specific-POS and SWAS-Related-POS) from the third round onward (i.e., excluding the two practice rounds). We did not include the figures for the category SWAS-Mention and for the negative polarity of SWAS-Specific and SWAS-Related because their frequency is low and the corresponding scores show a rather erratic behavior. We used this form of IAA scores as a tool for identifying problematic categories, or annotators that may have misunderstood parts of the guidelines.

In Figure 5 we report Krippendorff’s alpha scores for overall inter-annotator agreement between four annotators at the dimensional level (Attention, Emotional Engagement, Mental Imagery, Transportation, Impact). Note that the annotation was carried out using the tag set shown in Figure 2, however, for the purposes of visualization, it has been converted to the reconceptualized SWAS construct shown in Figure 8 (i.e., the SWAS-Related tags have been re-assigned to the dimensions of the SWAS-Specific category and the new “Impact” dimension).

Figure 6 shows the evolution of the mean Cohen’s kappa scores for each annotator. Mean kappa scores were obtained by calculating the scores for all pairs of annotators (considering just the “all” tag, obtained by checking if a sentence was annotated or not, independently from the assigned tag) and then calculating the mean value for each annotator. Thus, the values offer an indication of how much one annotator agrees with all the others. We observe two main trends. First, there is a clear improvement through the rounds; second, two annotators tend to always reach the highest scores, showing a better ability to agree with the others.

Figure 7 shows the evolution of the Cohen’s kappa scores between the four individual annotators and the curator (the first author of this paper, who originally developed the Story World Absorption Scale, and was involved in the annotation process as a group leader) for round 7 until 15. The reason for this is that the rounds before round 7 were annotated in the Brat software, which did not allow curation. The relative flat lines in Figure 7 can be explained by the fact that the curator curated the annotations at the end of the project, when the tag set was already consolidated.

4.3. Annotation difficulties

During the annotation process we encountered a couple of difficulties that we had to contend with and that we feel should be discussed here. The first one concerns the fact that we were dealing with very idiosyncratic natural language specific to communication on the Goodreads platform. This made it difficult to tag certain segments for several reasons, such as spelling mistakes, non-grammatical sentence structures or unusual punctuation. This, of course, led to problems for the annotators when trying to follow specific rules, such as only tagging complete clauses. We decided to be fairly lenient with this rule, following it as much as possible, but still tagging something that clearly matched one of our categories, even if the reviewer did not include a verb or a subject in their sentence. Reviewers also tended to use specific online review lingo, such as certain abbreviations, the Goodreads “spoiler” function (i.e., being able to hide spoilers for a book under a hyperlink), emojis or short outbursts of emotion expressed typographically (e.g., “AGHHHHHHHH” or *breaks down in tears* or “HA HA HA HA HA”). In these cases, we followed the general rule, if you have to infer absorption, because you cannot find a conceptual or semantic match, you do not tag a segment (i.e., we could argue that all three of the examples above probably indicate some form of emotional engagement with a book, but as it is not clear what kind and with what aspect of the book, we do not tag for it).

The next main difficulty is related to the fact that none of the annotators, nor the curator in this project are native English speakers. As many reviewers on the Goodreads platform and in our corpus are not native speakers either, this sometimes led to lengthy discussions about what certain expressions meant and whether they should be tagged. In these cases, we asked our panel of English-speaking absorption experts for advice on how to understand certain expressions. When the experts did not agree with each other, or when they advised us that an expression was ambiguous, we decided not to tag at all. In general, if the annotators had to infer too much from a review (i.e., when an annotator started to make inferences such as “perhaps the reviewer meant to say …” or “if the reviewer meant …, we could tag it as absorption”), we decided not to tag for a unit.

Another issue was concerned with categories we added to the tag set in the early practice rounds, but had to delete half-way through the annotation process, as we realized the statements these categories encompassed were too ubiquitous in the corpus. One example of this was expressions of general love for a character, a book, or an author (e.g., “I absolutely love this character”, or “I love everything Terry Pratchett writes”). Expressions of love were present in almost every 4- or 5-star rated review, and thus we considered this more a peculiarity of the English language or of the genre of book reviews, rather than an expression specific to the experience of absorption.

Related to this was the issue of several categories in our tag set overlapping to such an extent, that it was difficult to justify why we needed two separate categories. In those cases, we decided to merge the tags. For example, at the beginning of the annotation process, we thought it would be interesting to distinguish between general passive (e.g., “The book absorbed me”) or active statements of absorption (e.g., “I was absorbed in the book”). We realized that the distinction is merely grammatical, but that most reviewers tend to talk about the book or story as being the active agent in an absorption experience, whether or not they put themselves as the leading subject of a sentence. For example, an expression such as “I was hooked by the book”, would have to be tagged as “active general absorption”, as the subject is “I”, however, the book is “hooking” the reader and thus is the actual active agent in this phrase.

5. Curation and creation of annotation guidelines

Throughout the annotation process, the team kept finetuning the annotation guidelines and adding examples from the reviews, where we could find them, for all of the different absorption categories (both examples of the presence of absorption as well as the negation of absorption). We felt it necessary to add these examples to help future researchers who may want to use the tag set to familiarize themselves with the idiosyncratic natural language found on Goodreads, as, at times, it differed quite a bit from the original wordings on the SWAS. The guidelines follow the new conceptualization of the SWAS as outlined in Figure 8 and are published separately (Kuijpers, Lendvai, et al., “Absorption in Online Reviews of Books: Presenting the English-Language AbsORB Metadata Corpus and Annotation Guidelines”) and shared on Open Science Framework (Kuijpers et al., Absorption in Online Book Reviews) to be used and adapted freely by other researchers. When compiling the annotation guidelines, we realized that for some categories we did not find any matches, semantic or conceptual. We still decided to leave in any category that at least had one match - whether that be for the presence of that tag or the negation of it - as we felt that the fact that we could not find matches, was meaningful in its own way. One example of such a category is the negation of A1 (Altered sense of time). We found several matches in the corpus for the presence of this category, but none for the negation of it, which is fairly understandable as reviewers are unlikely to comment on the fact that their perception of time stayed the same during reading. For other categories it was rare or impossible to find semantic matches. This was the case for EE12 (Participatory response), for which the example statement reads “I wanted to involve myself in the story events”, describing in unambiguous terms what the category of participatory response is about. However, reviewers rarely use similar terms to ‘tell’ about their feelings of participatory response, but rather ‘show’ that they were responding in a participatory manner (cf. work in narratology about the difference between showing and telling, Klauk and Köppe). For example, matches we found for this category read “In my mind I was screaming ‘WATCH OUT’ and ‘Don’t walk down this street by yourself in the middle of the night’”.

With the finalized guidelines, the first author curated the final corpus through the use of the INCEpTION software, which offers a useful function for curation. This function allows the curator to see all of the annotations from each of the annotators per text (per review in our case). The software automatically curates those instances where 2 or more annotators tagged the exact same unit with the exact same tag. The curator went through the rest of the annotations and made executive decisions about the gold standard – including the best fitting unit of tagging and tagging category for each segment. These decisions were based on the discussions throughout the annotation process as well as the years of research the first author has conducted on the topic of absorption. It needs to be noted that, even with such a complex abstract concept to be tagged and quite extensive guidelines, there were no instances where the curator found a segment that should have been annotated, but where none of the annotators had picked up on anything. The differences between annotations from the different annotators, mostly involved tagging the same unit, but giving different absorption categories (understandable with a multidimensional construct), or using the same tagging category, but tagging different units of tagging (e.g., one annotator including a subclause, but another annotator excluding the same subclause).

6. Validation and reconceptualization of the SWAS

When working on consolidating the tag set for the purposes of sharing the annotation guidelines we kept the original aim of this project, which was to validate the SWAS, in mind. We set out to see whether reviewers in online book reviews express themselves similarly or differently about being absorbed to researchers trying to capture absorption with self-report instruments. We did not necessarily set out to reconceptualize the SWAS, but this happened organically, over the course of the annotation process, as we realized that certain theoretical aspects of absorption, such as effortless engagement (Bálint et al.), were mentioned by reviewers, but not reflected in the original SWAS statements, or that reviewers were mentioning aspects to absorbed reading that we had not even considered as researchers (such as a sense of addiction to a text, for example).

One interesting challenge we encountered was the uneven distribution of statements over the original dimensions of the SWAS. The SWAS started out with a slightly uneven distribution, in that Mental Imagery only included three statements, whereas the other three dimensions included five statements. This was the result of two rounds of factor analysis in which the list of Mental Imagery statements was shortened and shortened, as the statements did not seem to be as important to the overall concept of absorption as the statements on the other three dimensions (see Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption” for the full description of the development of the original list of statements). The annotation work in this project showed that this uneven distribution is also present in reviewers’ descriptions of their reading experiences. Mental Imagery was one of the least mentioned categories overall – together with Transportation – and only one statement was added to the Mental Imagery category over the course of the annotation process. Emotional Engagement on the other hand was one of the categories that reviewers mentioned the most, and to which the most statements were added. This is a testament to the importance of emotional engagement with characters for achieving a sense of absorption during reading. Although the biggest number of annotations for the A3 statement on the Attention dimension would corroborate the conclusion of Kuijpers (“Exploring the Dimensional Relationships of Story World Absorption: A Commentary on the Role of Attention during Absorbed Reading”) that Attention seems to be at the core of the absorption construct and potentially functions as a precondition for the other dimensions, the results of the annotation work could be interpreted as Emotional Engagement playing an equal if not greater role in absorption experience than assumed.

For the reconceptualization of the SWAS, we integrated all of the SWAS-Specific and the SWAS-Related categories into one new overall construct. For each of the new statements we asked ourselves whether they could be classified under one of the four original dimensions on the SWAS: Attention, Emotional Engagement, Mental Imagery, or Transportation. Thirteen of them could be classified as such, but five of them could not be considered part of any of the four existing dimensions, while still referring to some theoretical aspect of absorption. For these five categories, we came up with a new theoretical dimension and called it Impact. This new dimension consists of IM1 (Effortless engagement), IM2 (Wish to reread), IM3 (Anticipation book series), IM4 (Addiction), and IM5 (Lingering story feelings). We decided on the conceptualization of Impact, as each of these categories describes a form of (longer-lasting) impact on the reader. When the SWAS was originally developed, the authors empirically tested whether the related evaluative responses of enjoyment and appreciation could be considered part of the SWAS construct or should rather be considered separately (cf. Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption”). Based on the results of their factor analyses, they decided to treat these evaluative responses separately, but emphasized the close relationship between absorption, enjoyment and appreciation. Further factor analytic work would need to be done on the new conceptualization of Story World Absorption presented here to see whether Impact should be considered closely related but separate – as enjoyment and appreciation are – or whether it should indeed be considered a part of the Story World Absorption concept.

Figure 8 provides a visualization of our final tag set as an elaboration of the original SWAS statements shown earlier in Figure 1. As can be seen in Figure 8 there are some categories that received more curations than others. It is telling that some of the newly added categories, such as the five categories for the new dimension of Impact received the highest number of curations, which clearly indicates the need for a reconceptualization of Story World Absorption, at least within the context of investigating this concept in online reader reviews. One interesting finding was the large amount of negated IM1 (Effortless engagement) in contrast to all of the other categories. We found a lot of instances in which reviewers mentioned having trouble “getting into the story” at first, before starting to feel absorbed or otherwise engaged with it. Curations using the SWAS-Mention layer were also counted towards the total amount of curations, but they only accounted for 4 percent of the overall curations. The SWAS-Mention layer was used most to annotate for IM5 (Lingering story feelings), IM2 (Wish to reread) and A3 (General sense of absorption).

7. General Discussion

In this paper, we introduced a methodology for annotating absorption in online book reviews and tested its validity and useability through a series of inter-annotator agreement studies. In this discussion, we will focus on how the results of this project inform potential reconceptualization of the SWAS based on the annotation work, and the consequences of these findings for the use of the SWAS in further experimental research. Finally, we will comment on some of the limitations of this study and how we think these can be addressed in further research.

Reconceptualization and future of the SWAS

One of the main reasons for conducting this research was to validate the SWAS against unprompted readers’ expressions of absorption. In developing the SWAS originally, great care was taken to find a middle ground between practicality and usability of the instrument in experimental settings on the one hand and careful theoretical articulation of the measured constructs on the other (Kuijpers, Hakemulder, et al., “Exploring Absorbing Reading Experiences: Developing and Validating a Self-Report Measure of Story World Absorption”). However, once an instrument is tested and deemed valid in lab environments, able to reliably measure the theoretical constructs it aims to capture, we should not forget to keep checking in with actual readers in actual reading environments. This is the only way to make sure we are measuring the type of absorption people experience in daily life, rather than a type that is specific to lab settings.

The present study has shown that the Story World Absorption construct we have been using within experimental and survey research so far, is lacking in several areas. First, some theoretical aspects of absorption, such as effortless engagement and inability to stop reading, were not reflected in the SWAS instrument, or in related instruments for that matter (e.g., Busselle and Bilandzic; Green and Brock). These were some of the most mentioned categories in the online reader reviews (see Figure 8) and based on that we would highly recommend adding items that measure these concepts (i.e., IM1 (Effortless engagement): “I devoured this book/it was an easy read” and A7 (Inability to stop reading): “I could not put this book down/I did not want to put this book down”) to the SWAS.

Second, we realized that negatively valenced emotional engagement, such as fear and anger, were strong indicators of an absorbing reading experience, but neither the SWAS or related instruments include such items and instead tend to focus on more positive emotional engagement, such as empathy or sympathy or more general emotional engagement, such as identification or perspective taking. We think adding such negative items, especially in experimental research that looks at engaging with morally ambiguous characters (de Jonge et al.) could be really fruitful.

Third, emotional engagement was one of the dimensions that was used the most in annotating the reviews, indicating that relationships with characters are great contributing factors to a feeling of absorption for most readers. Thus, expanding the dimension of emotional engagement to include more “reactive engagement” type of emotional responses (cf. Kuijpers, “Exploring the Dimensional Relationships of Story World Absorption: A Commentary on the Role of Attention during Absorbed Reading”), such as participatory response, para-social response, emotional understanding and wishful identification, is highly recommended for those researchers interested in this aspect of absorption specifically.

Of course, there were some additions made to the reconceptualization of the SWAS shown in Figure 8 that are specific to the types of reader responses found on a platform like Goodreads, such as IM3 (Anticipation book series) or IM2 (Wish to reread), and which therefore are perhaps not that relevant for use within experimental settings. The nature of the online book review is such that reader responses refer to an entire book or sometimes an entire book series, which can also lead to discussion of themes that will perhaps have less relevance in experimental settings, where participants read short experimenter-selected texts (e.g., IM4 (Addiction): “I am addicted to this book/I cannot get enough of this book” or IM5 (Lingering story feelings): “This book stayed with me for a while”). It is also plausible that the social setting in which these reviews are posted has influenced what reviewers talk about and how they talk about it, making it less likely that similar responses will occur within experimental settings. This is of particular interest in the romance community on Goodreads, where review language is mimicked among reviewers (cf. Kuijpers, “Bodily Involvement in Readers’ Online Book Reviews: Applying Text World Theory to Examine Absorption in Unprompted Reader Response”), and focuses mostly on deep emotional engagement with characters (i.e., para-social responses are particularly common). The question remains though, whether such deep emotional connections also occur in experimental or survey settings, which, of course, will remain a mystery to us unless we ask our participants about it specifically. The next step in reconceptualizing the SWAS, currently being conducted by the first author of this paper, is to test and validate a new version of the SWAS in different contexts (i.e., in online and face-to-face (shared) reading settings) using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The expected result will be an adapted and expanded version of the SWAS using more simple language, that includes the categories added during this project, to be used in future experimental settings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that we need to address here. First of all, there is the nature of the data we are working with, that prohibits us from sharing all of the particulars of the work we conducted for this project. Our final metadata corpus consists of 493 annotated and curated reviews (see Kuijpers, Lendvai, et al., “Absorption in Online Reviews of Books: Presenting the English-Language AbsORB Metadata Corpus and Annotation Guidelines” for a description of how the corpus was built; see Kuijpers et al., Absorption in Online Book Reviews for the metadata corpus itself). Due to ethical and legal reasons, however, we were unable to add the full text reviews to this metadata corpus. The type of data we are dealing with (i.e., testimonials of a potentially personal nature, which are shared publicly on a freely accessible online platform) poses a challenging ethical dilemma. Even though this data is freely accessible, “ease of access does not mean ethical access” (Giaxoglou; cf. Thomas, “Reading the Readers”). As we are unable to ask the reviewers who wrote the texts for their consent to use their texts, we have to decide ourselves how to treat this data ethically speaking. Now, there are researchers who argue that as we are looking for trends and patterns in the data and not at individual reviews, we could anonymize the data and be exempt from asking for consent, as these reviewers made the decision to publish these texts on an openly accessible forum (Wilkinson and Thelwall). On the other hand, there are those that argue that as these texts are carefully and creatively written opinion pieces, we should identify the authors of these texts and give credit where credit is due, as these reviewers made the decision to publish these texts on an openly accessible forum (Thomas, “Reading the Readers”). The main question here is how do you balance your respect for privacy laws versus copyright law, while upholding your responsibility to the scientific community to share your work openly in order for it to be scrutinized? We turned to several different entities and organizations for legal advice (e.g., University Library of Basel University, RISE (Research and Infrastructure Support University of Basel), DHLawtool, ELDAH (Ethics and Legality in Digital Arts and Humanities)), but were unable to find a solution that everyone we spoke to would agree upon. The information currently available for research in Switzerland (where this research originated) does not allow reuse of these types of texts. However, recent European directives introduced significant exemptions for text and data mining for research purposes (e.g., Directive (EU) 2019/790 on Copyright in the Digital Single Market). Similar exemptions have already been included in other national laws such as the Urheberrechts-Wissensgesellschafts-Gesetz in Germany, and it is expected that Switzerland will soon follow (cf. Dossier “Modernisierung des Urheberrechts”, Meyer). With all of this in mind, we chose to give more prominence to privacy law than copyright law, as underaged users are granted extended protection under the new EU law (and we are dealing with a potentially large number of underage reviewers), and everyday language use and common phrasings (such as can be found on Goodreads) are difficult to copyright.

Thus, we prepared two versions of our corpus, one with the annotations, the annotation category, and the annotation subcategory for every annotation, but without the full review texts. This version of the corpus is publicly available on Open Science Framework (Kuijpers et al., Absorption in Online Book Reviews). For researchers who would be interested to work with the complete corpus including full review texts, we prepared a second corpus, which includes all of the above metadata, the information on our annotations and the full review texts which have been fully anonymized (i.e., no identifying information on the reviewers is included and no direct links are given to the Goodreads website). Researchers can contact the first author of this paper with a proposal to obtain access to the complete corpus for research purposes only. In this decision, we followed the guidelines from the APA on “protected access open data” (“Open Science Badges”).

Second, we need to ask ourselves how far we can think of online reviews as natural reader responses that are comparable to reader responses gathered in experimental settings? As Kuijpers (“Bodily Involvement in Readers’ Online Book Reviews: Applying Text World Theory to Examine Absorption in Unprompted Reader Response”) points out “Does the social context in which people post their reviews change their expression of absorption? Is the experience of absorption broadened by the conversations about what is being read, which in themselves can also be absorbing?” (7). An additional concern is that these reviews are posted on a platform that has particular commercial interest in the production of reader reviews, which may also have an influence on the content of the reviews that is difficult to gauge (Thomas, Literature and Social Media).

Thirdly, this annotation scheme is focused on textual examples of absorption that show a semantic or conceptual match with the statements in our extended Story World Absorption construct. This means that there were instances of absorption that simply could not be annotated for using our scheme. This can, for example, be due to the use of gifs or images in reviews for which it is impossible to annotate using a text-based scheme. Another, more intriguing example of real-world input is the trend of readers talking directly to characters in their reviews, or even assuming the persona of a character in a book to comment on story-world events. These forms of narrative play indicate a high level of absorption, even when no semantic or conceptual matches with any of the tag set statements can be found (see Kuijpers, “Bodily Involvement in Readers’ Online Book Reviews: Applying Text World Theory to Examine Absorption in Unprompted Reader Response” for a case study analysis of such a review using a Text World Theory approach).

Finally, our annotation scheme is unable to account for degrees of absorption expressed by reviewers. At this point, the annotation guidelines will help researchers classify whether a review expresses a certain form of absorption or not. However, reviewers often express their enthusiasm for a book or reading experience in different ways, which may refer to different levels of intensity with which they experienced absorption during reading. Of course, this is a question that can only be asked of reviewers directly and therefore would perhaps require a different empirical approach.

As a final note, digital social reading (cf. Pianzola; Rebora, Boot, et al.) is a growing phenomenon that deserves scholarly attention, as more and more people, especially young adults, engage in these kinds of digital reading practices. The digital humanities, and related fields interested in such reading practices, will need resources like the corpus and annotation guidelines developed for this project (Kuijpers, Lendvai, et al., “Absorption in Online Reviews of Books: Presenting the English-Language AbsORB Metadata Corpus and Annotation Guidelines”) and the annotation process presented in this paper, to understand the different ways in which this phenomenon can be studied.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation’s Digital Lives grant (10DL15_183194) and Eccellenza grant (PCEFP1_203293).

Peer reviewer: Evelyn Gius

Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OPF0FV