In 2004, Robert McHenry, former editor-in-chief of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, compared Wikipedia to a public restroom: the facilities may appear clean and offer a sense of security to users, but they never know who used the restroom before (Fallis 1662). This idea pretty much sums up the discussion about Wikipedia in the early twenty-first century when its value, importance, and usefulness were compared to printed encyclopedias. Currently, Wikipedia has editions in more than 300 languages. The Spanish version has nearly 2 million entries and more than 6 million registered users. For instance, the entry about Mario Vargas Llosa, a Peruvian-born writer who won the Nobel Prize in 2010, has versions in nearly 90 languages and the Spanish page receives an average of 2,609 visits daily. These numbers show that Wikipedia is one of the most used tools for learning more about Peruvian literature, its writers, and their works. Comparison to other (non-digital) encyclopedias is not necessary nowadays, because Wikipedia has become an object of study for different disciplines. However, the field of Latin American literary studies has not yet explored the potential of Wikipedia for researching the writing and dissemination of the history of national literatures. In this way, this paper is the first study that uses a data-driven approach to analyze the representation of a Latin American literature in Wikipedia.

Like the histories of Latin-American literature written in the nineteenth century (González-Stephan), Wikipedia is now a space where users build a sense of community by creating, editing, and visiting articles. However, there is a key difference: if the nineteenth century/written histories relied on the genius of the intellectual who interpreted and imposed the idea of the nation, the digital world allows the interaction of editors, who dialogue and discuss their ideas. They use Wikipedia to propose different narrations of the nation or give notability to specific people. Wikipedia also allows for research across a large number of languages, not only those spoken in different countries, but within the same political area.

For instance, Peru is a multicultural and multilingual country with 48 indigenous languages used within the national territory and recognized by the Ministry of Culture. Nevertheless, the most spoken language in Peru is Spanish (82.6% of total population), followed by Quechua (13.9%) and Aymara (1.7%) (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática 18). These three languages have Wikipedia versions. In this paper, I explore two versions, Spanish and Quechua, to analyze the representation of Peruvian literature and the inclusion/exclusion of authors in the encyclopedia, especially focusing on the representation of cultural diversity. This study shows that, as an extension of the Peruvian literary criticism of the last century, Wikipedia editors focus on certain areas to define a national literature that excludes Amazonian regions in Peru (Amazonas, Loreto, Madre de Dios, San Martín, and Ucayali). At the same time, Wikipedia allows the Quechua community to utilize the encyclopedia in order to provide an alternative literary corpus and history to the critical discourse in Spanish.

Data

My goal is to analyze the representation of a national literature on Wikipedia, because it works as a bridge between academic knowledge and people outside the academy. Concerning the reader motivations to using Wikipedia, Lemmerich et al. state the importance of school-related reading in the Spanish version: “While work or school-related motivations account for 10% in English Wikipedia, they account for over three times as much (31%) in Spanish Wikipedia”. They also explain that in-depth reading or intrinsic learning is more frequent in less developed countries, such as Peru. For example, nowadays the library would not be as good an option for a person looking for the “2010 Nobel Prize in Literature winner”, because there is a larger, faster and more accessible source than a non-digital encyclopedia: Wikipedia (Fallis 1667). For this reason, I scraped Wikipedia directly using RStudio, a GUI for the R language that retrieves all the information the Wikipedia reader has immediate access to.

The internet has a changing nature: a Wikipedia article could have one thousand words today, but three thousand words next week. All the data for this research were retrieved from Wikipedia on December 5th, 2021. Although the data will have changed in the last months, this variation does not invalidate the analysis: my conclusions explain a concrete moment in the digital representation of Peruvian literature. The first step in the scraping process was to identify what writers were Peruvian according to each Wikipedia version. The retrieval is based on the category “Peruvian Writers”, which shows a list of writers and subcategories. On the Quechua Wikipedia, this category, “Qillqaq (Piruw)”, included 222 writers and no subcategories.

The Spanish Wikipedia was a more challenging case because the category “Escritores de Perú” included several subcategories in addition to the list of more than 300 Peruvian writers. Only twelve subcategories were pertinent when scraping data from Wikipedia: “Escritoras de Perú” (Peruvian Women Writers), “Poetisas de Perú” (Peruvian Women Poets), “Escritores de Lima” (Writers from Lima), “Cuentistas de Perú” (Peruvian Short Story Writers), “Dramaturgos de Perú” (Peruvian Playwriters), “Escritores de Literatura Fantástica de Perú” (Peruvian Speculative Fiction Writers), “Escritores de Literatura Infantil de Perú” (Peruvian Writers of Children Literature), “Escritores de Novelas Históricas de Perú” (Peruvian Historical Fiction Writers), “Novelistas de Perú” (Peruvian Novelists), “Poetas de Perú” (Peruvian Poets), “Poetas de Perú del siglo XX” (20th-Century Peruvian Poets), and “Escritores LGTB de Perú” (LGTB Writers from Peru). Three prominent literary writers were included, because they did not appear in the lists of Peruvian writers, but were subcategories in themselves: Mario Vargas Llosa, José Carlos Mariátegui, and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. The final number of Peruvian writers in the Spanish version was 609.

To collect the data used in this research, I scraped information from articles and information pages in Wikipedia. A Wikipedia entry includes a title (Peruvian writer’s name), encyclopedic information, images, references, and usually an infobox (a table showing relevant information about the author). From these entries, information about the writer is accessible: birthplace, date of birth, literary works, among others. Information pages, on the other hand, contain data that describe the article, not the writer. Wikipedia readers can visit the page to find out the total number of article words, date of page creation, date of latest edit, page views, etc. These two sources allow for analyzing three types of information: data about the writer featured in the Wikipedia article, data about the creation of the article, and data about its reception. The possibility to retrieve all this information and the multilingual nature of the platform are the principal advantages of Wikipedia when researching the construction of national literatures in the digital world.

Finally, I cleaned the data manually. In this context, cleaning means correcting spelling mistakes, deleting duplicates, or completing missing information. Two examples show that non-uniform information creates obstacles when scraping data from Wikipedia. Infoboxes provide the writer’s birthplace in a format easy to scrape (a table), but places are not consistent. Different spellings are the most prominent case: Áncash / Ancash, Cusco / Cuzco, or Junín / Junin. Editors also provide the city or town but omit the region: Iquitos instead of Loreto and Trujillo instead of La Libertad. When retrieving data from information pages there are similar problems. The date of page creation has two different formats: hour - day - month word - year (2:00 pm - 10 - August - 2021) and month number - day - year - hour (08 - 10 - 2021 - 2:00 pm). Both cases require researchers to clean data carefully. After this process, I used RStudio again to create dataframes allowing for the examination of all the information and to visualize the data.

Wikipedia and Peruvian regional literature

Traditionally, Peru has been considered a country with three geographical regions: the coastal desert next to the Pacific Ocean, the Andes running through the middle, and the jungle, which is part of the Amazonian region. This geography allows for a classification of the 25 Peruvian political regions: the coast (9 regions and 11.7% of the national territory): Callao, Ica, La Libertad, Lambayeque, Lima, Moquegua, Piura, Tacna, and Tumbes; the Andes (11 regions and 28%): Áncash, Apurímac, Arequipa, Ayacucho, Cajamarca, Cusco, Huancavelica, Huánuco, Junín, Pasco, and Puno; and the Amazon (5 regions and 60.3%): Amazonas, Loreto, Madre de Dios, San Martín, and Ucayali. Peru is also a highly centralized country with the most populated and developed cities on the long narrow coast (the 3 most populated areas are coastal regions with more than 43% of the total population). Because Wikipedia provides the writers’ birthplaces, I am exploring the representation of Peruvian regional literature in Wikipedia and its correlation with 3 factors: population, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and Internet access.

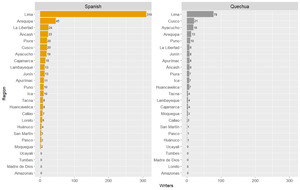

Using information from infoboxes and Wikipedia article content, I identified the number of authors from every Peruvian region (see Figure 1). There are 574 writers born in Peruvian regions in the Spanish Wikipedia (18 authors were born in foreign countries and 17 have no birthplace listed because they use pseudonyms or the information is incomplete) and 214 in the Quechua version (3 writers were born outside of Peru and 5 have incomplete information). The fact that there are only four authors born in Spain in the Spanish Wikipedia, and none in the Quechua Wikipedia, is a surprise when considering the history of Peru, a Spanish colony until 1821. Indeed, on the Spanish Wikipedia, colonial Peruvian writers, many of them born in the Iberian Peninsula, do not have an article or are not included in the category “Peruvian Writers”. Furthermore, the category “Cronistas de Perú” (Peruvian Chroniclers) is totally different from “Escritores de Perú”. It means that around 30 authors, Peruvian and Spanish, who wrote about the conquest and the early years of the colony, are not considered representatives of the national literary tradition according to the Spanish Wikipedia.[1]

Figure 1 also reveals that writers from the coast and the Andes are comprehensively represented. The top 10 regions of birth include the regions from both areas, while the Amazon is almost not present. On the Spanish Wikipedia, the Amazonian regions are in the seventeenth and nineteenth position (Loreto with 6 authors and San Martín with 3), and there is only one Amazonian region in the Quechua version (San Martín with 1 writer). At the same time, 3 areas from the Amazon are totally absent in the Spanish list; 4 are absent in the Quechua one. To be clear, those places do appear on both lists with a 0 next to the name of region[2]. I added them to the list after retrieving all data from both Wikipedias, because of my previous knowledge of Peruvian political division. However, a regular reader of Wikipedia could infer that literary production does not exist within these Peruvian regions.

The prominence of regions such as Lima, Arequipa, La Libertad o Cusco, and the absence of the Amazon is related to external factors. Figure 2 and 3 reveals that the distribution of the population and GDP in Peru has a high correlation with the number of authors in both Wikipedias (for instance, rPearson = 0.98 and 0.99 for the Spanish version). This almost linear relation shows that regions with more population density and economic development have more representation. In the case of the Quechua Wikipedia, Cusco and Ayacucho stand out, although are not outliers, because the order of the regions of birth has changed. In comparison to the Spanish version, Andean regions where there are more Quechua speakers have moved to higher positions. In other words, their representativeness has increased. In Cusco and Ayacucho, 54.2% and 62.5% of the population speak Quechua respectively.[3] Puno, with 42.3% Quechua speakers, now occupies the fifth position. However, this percentage of speakers has a very low influence on the representation of the Peruvian regional literature in Wikipedia (rPearson = 0.15), while the population and GDP still have a strong correlation (rPearson = 0.93 and 0.94 for the Quechua Wikipedia). For this reason, I suggest that the concentration of people (labor) and money (capital) as an indicator of socioeconomic development is a central predictor of the Peruvian literary geography on both Wikipedias.

Furthermore, Internet access has a very low correlation (rPearson = 0.36). In general, the percentage of the population with access to the Internet in the Peruvian regions ranges from 38% (Loreto and Cusco with the lowest percentages) to 80% (Lima and Callao in the first places). Figure 4 shows that regions with an access rate higher than 70% have a minimal representation on Wikipedia. For instance, two Amazonian areas (Madre de Dios and Ucayali) have an access rate higher than 50%, but they also have no writers on both Wikipedias. In fact, in the last years, regions in the Amazon have had the highest increase in Internet access: “Las regiones con mayor crecimiento porcentual de conexiones a Internet fijo respecto al mismo periodo del año pasado fueron Amazonas (114,7%), Pasco (69%), Apurímac (44,6%) y Madre de Dios (40,6%)” (“The regions with the highest percentage increase in wired Internet connections with respect to the same period last year were Amazonas (114.7%), Pasco (69%), Apurímac (44.6%) and Madre de Dios (40,6%)”) (“Reporte estadístico”). Although some research identifies availability of connectivity as the best predictor of digital representation (Graham, Straumann, and Hogan), a higher connectivity did not mean an increase in the representativeness of Amazonian literature as part of Peruvian literature on Wikipedia. Technology used to access the Internet may provide an explanation. In the first quarter of 2021, 86.7% of the Peruvian population accessed the Internet through a cell phone, while only 14.9% used a computer (“El 55.0% de los hogares”). Therefore, in Peru, more accessibility does not mean more representation in the digital world, because most Peruvians use cell phones, which impose restrictions when editing a Wikipedia entry.

I have no doubt that socioeconomic development influences the representation of Peruvian regional literature in the Spanish and Quechua Wikipedias. Of course, GDP refers to economy, but it also gives an idea of the resources that regional governments can use for building and maintaining infrastructure, creating jobs, improving public schools, or investing in cultural activities. This translates into an environment favorable for editing Wikipedia entries. I want to emphasize here three reasons for the unequal digital representation pointed out by Graham and Dittus (108-10) that may also explain the Peruvian case: capacity to engage in voluntary labor, economic conditions to spend time writing on Wikipedia, and digital literacy.

While digital representation of Peruvian regional literature reflects inequality in capital distribution, I also suggest that it reflects inequality in literary studies. As Samoilenko et al. proposes, it is not unusual that Wikipedia extends academic biases: “Thus we find that Wikipedia, despite offering a democratised way of writing about history, reiterates similar biases that are found in the ‘ivory tower’ of academic historiography” (“Analysing Timelines”). In the following paragraphs, I offer an overview that demonstrates that both Wikipedias, Spanish and Quechua, reproduce how 20th-century Peruvian literary criticism approached the construction of national literature.

In the first half of the 20th century, the canon of Peruvian writers consisted of those born originally either in Spain or in Lima: Juan del Valle y Caviedes (1645-1697), Manuel Ascencio Segura (1805-1871), Felipe Pardo y Aliaga (1806-1868), Carlos Augusto Salaverry (1830-1891), Ricardo Palma (1833-1919), José Santos Chocano (1875-1934), among others. There were only two exceptions: Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616) and Mariano Melgar (1790-1815), who were from Andean cities (Cusco and Arequipa). The literary field changed around the 1960s when an alternative canon arose: the post-oligarchic canon (García-Bedoya Maguiña 160). Due to the changes that occurred in Peruvian society in the preceding decades, the most prominent authors were related to different regions, although most of them published in Lima. This is the case of writers such as César Vallejo (La Libertad, 1892-1938), Mario Vargas Llosa (Arequipa, 1936), and José María Arguedas (Apurímac, 1911-1969). By the end of the 20th century, with authors from the coast and the Andes considered canonical writers, no author from the Peruvian Amazon occupied a predominant position in the corpus of national literature.

This tendency to exclude the cultural contributions of the Amazon can be traced back to the foundation of Peruvian literary studies at the beginning of the century. In 1905, Jose de la Riva-Agüero published Carácter de la literatura del Perú independiente, a critical and historiographical work that began to conceptualize Peruvian literature: “La literatura del Perú, á partir de la Conquista, es literatura castellana provincial” (“The literature of Peru, after the Conquest, is provincial Castilian literature”)[4] (Riva-Agüero 220). Peruvian literature is part of the Spanish tradition: a nation that repeats European models. It makes sense that the most prominent Peruvian writers in this book were white men who wrote in Spanish and were mostly from Lima. In the 1920s, two critics responded to this approach to emphasize an aspect of Peruvian literature that had been totally ignored by Riva-Agüero. The literary history proposed by Luis Alberto Sánchez[5] included pre-Hispanic literature and indigenous folklore, especially cultural manifestations in Quechua (29). And in his chapter “Proceso a la literatura peruana”, José Carlos Mariátegui stated: “Una literatura indígena, si debe venir, vendrá a su tiempo. Cuando los propios indios estén en grado de producirla” (“An indigenous literature, if it must come, will come in its own time. When the Indians themselves are able to produce it”) (283). Mariátegui was confident that literature would become the cultural expression of the indigenous population. In short, if Sánchez placed indigenous literature in the past, Mariátegui imagined it as the national literature of the future. The texts of literary criticism and history that sought to construct a Peruvian literature did not change these approaches much in the following decades until the 1980s when Antonio Cornejo Polar (188) proposed to include ethnic literatures (oral literary expressions in indigenous languages) as part of the national tradition.

The above summary reveals that the construction of Peruvian literature oscillated between two geographical spaces: the coast (particularly Lima) and the Andean mountains. Riva-Agüero’s proposal concentrated on Peruvian literature written in Spanish and located basically in Lima, with writers such as Felipe Pardo y Aliaga and Ricardo Palma. Sánchez and Mariátegui referred exclusively to the Andean region: the former used the term aboriginal literature, but only described Inca cultural expressions in Quechua; the latter proposed the possibility of an indigenous literature after discussing indigenism, which represented the abuses against indigenous people in the Andes. Although, theoretically, Cornejo Polar’s ethnic literatures encompassed all literary manifestations in indigenous languages, the critic is thinking exclusively of the Andean world. His three paradigmatic writers are quite evident: José Carlos Mariátegui, César Vallejo, and José María Arguedas; all of them renowned for including an Andean indigenous perspective in their work. Even at the beginning of the 21st century, this dual perspective continued to shape national literature. At the International Conference of Peruvian Narrative held in Spain (May 2005), a polemic arose concerning the fictional representation of the internal conflict in Peru (an armed conflict between the Government and guerilla groups like Shining Path). The controversy opposed two groups called “criollos” (in Peru, this word designates the cultural manifestations of the coast that have a European influence, as in the case of “música criolla”) and Andean writers. The former were authors from Lima who represented the conflict from that locus of enunciation, the latter wrote with an Andean perspective[6]. Therefore, it is urgent to ask: where was Amazonian literature when the critics imagined Peruvian literature? (At least for Cornejo Polar, Amazonian literature appears very briefly in footnote 57, page 125).

The Spanish and Quechua Wikipedias reiterate this exclusion of the Amazon in the national literary tradition. It is worth noting that Wikipedia editors use different criteria to evaluate articles, one of which is notability: “People are presumed notable if they have received significant coverage in multiple published secondary sources that are reliable, intellectually independent of each other, and independent of the subject” (“Wikipedia: notability”). The absence of Amazonian writers in historiography and criticism about Peruvian literature also means fewer academic papers, essays, or presentations about these Amazonian authors. This factor may influence the number of entries on regional writers. Wikipedia users do not have enough academic sources to write the articles or, if they do write them, the sources could not be considered sufficient to establish notability. For example, only 2 of the 9 articles on the Amazonian authors include more than 4 references. Paraphrasing Graham and Hogan (7), notability creates a sort of feedback loop. If a regional literature in Peru is underreported, there are no sources. If there are no sources, then Wikipedia editors do not always have enough information to report about that region.

The absence or exclusion of the Amazonian literary tradition is not the only strategy when constructing the Peruvian national literature. Literary studies have also narrowed this tradition. As Best Urday and Sucasaca acknowledge, the city of Iquitos, in the Loreto region, has been the center of Amazonian literary production:

La cultura letrada amazónica del siglo XX tuvo como eje principal a Iquitos. Esto se refleja en la presente antología que -al reunir autores que comienzan a publicar entre 1957 y 1989-, está conformada casi íntegramente por literatura procedente de dicha ciudad, evidenciando las principales líneas de trabajo del periodo, así como a sus autores más representativos.

(The Amazonian lettered culture of the twentieth century had Iquitos as its main hub. This is reflected in the present anthology which, by bringing together authors who began to publish between 1957 and 1989, is composed almost entirely of literature from that city, showing the main lines of work of the period, as well as its most representative authors). (Best Urday y Sucasaca 10)

Therefore, there are many studies of literary criticism on the literature in Iquitos (Loreto), but very little research has been done on the literary production in the other Amazonian regions. As a result, the terms Iquitos and Amazonia are often used interchangeably, because criticism reduces Amazonian literature to works written by authors from this city. The Spanish Wikipedia reiterates this process when, in the first paragraph of the article on Peruvian literature, the link “Literatura amazónica” leads to the article “Literatura iquiteña”.

In conclusion, as Graham et al. (159), I propose that digital representation is accelerating for those cultural traditions with a strong tradition of criticism and research: Peruvian literary expressions from the coast and the Andes. Nevertheless, in recent years, the literary tradition of the Amazonian regions is being rediscovered and consolidated thanks to research on the regional literatures or specific authors[7]. This process is taking place both in the academy and in the digital world, where contemporary writers disseminate their works. However, the Spanish and Quechua Wikipedias do not reflect this new flourishing context. Therefore, this section should end with a question: How can we engage user and communities interested in including the latest research on Amazonian literature?

Quechua Wikipedia and its challenges

After more than a hundred years, the writing of the history of Peruvian literature continues to be in Spanish: texts in Spanish that speak of a national literature in a country with around 50 languages. If the book includes a section about Quechua literature, it is in Spanish: Spanish-speaking writers who write to Spanish-speaking readers. However, technology and the internet offer the opportunity for communities to tell their own “historias” in their own language. In this section, I argue that Quechua Wikipedia is not just an imitation or an extension of the Spanish version, but a platform where users express their own concerns and preferences. In words of Massa and Scrinzi (213), the Quechua community possess a specific Linguistic Point of View (LPOV), that not only diverges from the Spanish LPOV, but also from the Neutral Point of View (a Wikipedia norm that requires writing entries representing all views without bias).

Since Wikipedia offers information not only about Peruvian authors, but also about the articles themselves, it is possible to compare two aspects of Wikipedia: the process of creating the article and its popularity (the process of receiving it). For the first case, I use two factors: the total number of words in the article and the total number of edits. The relationship between the two factors shows the preference or interest of Wikipedia users in a particular Peruvian author. For the second case, the number of edits and visits to the article in the last 30 days indicate the interest that the article generated at a specific time and its dissemination among users. These data demonstrate that different language versions of Wikipedia relate to different cultural communities that have their own motivations for creating, editing, and visiting articles, even if they inhabit the same territory.

On Wikipedia, writers whose articles are the longest and have the most edits are the most prominent. This means that there is interest in writing and updating their biographies, works, and cultural value. Mario Vargas Llosa is by far the most important Peruvian writer on the Spanish Wikipedia (see Figure 5). The Peruvian author not only constitutes a separate category (like José Carlos Mariátegui and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega), but his article is also the one with the highest number of edits (4930 editions). Juan Espinosa Medrano’s article is very similar in terms of the total number of words. However, the number of edits makes the difference (Espinosa Medrano’s entry has 471 edits), because Vargas Llosa is still publishing, while Espinosa Medrano died in the 17th-century. Although both axes (total words and total edits) have their own prominent writers, the authors with a canonical status on Wikipedia are those who combine both factors: their entries are constantly expanded and updated because the community believes that information about their life, work and cultural value should be disseminated. As such, users continue to edit and extend their articles.[8] These canonical authors do not necessarily have to be alive to be relevant. Mario Vargas Llosa, César Vallejo, and José María Arguedas are the most prestigious writers on the Spanish Wikipedia: Vallejo died in 1938 and Arguedas in 1969. Although they are no longer publishing, the user community extends their value to the present.

The field of prominent authors according to total words and total edits looks completely different in the Quechua Wikipedia (see Figure 6). First, the large difference in the number of words and edits in comparison to the Spanish version, which is due to a smaller community working to create and maintain the Quechua version, is remarkable. Moreover, the same authors (Mario Vargas Llosa, César Vallejo, and José María Arguedas) stand out, but their status is totally different. Vargas Llosa has the article with the most edits, but it is so brief that it only consists of a list of works. Arguedas is the only writer who can be considered prominent in this Wikipedia, because the user community not only lists his works, but also explain the value of his life and work (this author is widely recognized for his defense of Andean culture and for using Quechua-influenced Spanish in his literary works). In general, in this version of Wikipedia, the writers with the longest articles are those who use Quechua in their literary works, such as Carlos Falconí Aramburú and Andrés Alencastre Gutiérrez. In this way, the Quechua LPOV creates its own notability criteria, because writers that promote the Quechua language are more important than those with academic recognition.

Prestige is related to the construction of literary value, while popularity is the way in which the community interacts with a product at a given time[9]. In the period from November 6 to December 5, 2021 (30 days), the most popular Peruvian writer in the Spanish Wikipedia was Mario Vargas Llosa (see Figure 7). In fact, this writer is the most prominent no matter what encyclopedia criteria is evaluated. In addition to having a smaller community, editors and visitors interact much less with the Quechua Wikipedia[10]. In fact, no articles were edited during that month. Visits were also much lower: while the Vallejo page in the Spanish version had 25605 visits, the most popular author, Enrique López Albújar, on the Quechua encyclopedia only had 44 and Mario Vargas Llosa had 23.[11]

In addition to the tremendous numerical difference (the Spanish Wikipedia has 15,002 active users; the Quechua version: 36), it is obvious that Quechua and Spanish Wikipedia communities have their own LPOV’s and quite different ideas of their national literatures. So, two constructions of Peruvian literature coexist in Wikipedia. For example, the Quechua Wikipedia’s list of 222 Peruvian writers differs from the Spanish version. 154 of them appear both in the category “Escritores de Perú” (Spanish Wikipedia) and “Qillqaq (Piruw)” (Quechua Wikipedia). However, 44 are considered Peruvian writers only in the Quechua encyclopedia, not in the Spanish edition. Even though these 44 have entries in the Spanish Wikipedia, they are not part of the category “Escritores de Perú”. The reason for their inclusion in the Quechua Wikipedia is not based on language since most of them publish in Spanish, not in Quechua. This group, moreover, includes several non-fiction writers, which are part of different subcategories on the Spanish Wikipedia. While in the Quechua version, all writers are included in the same category regardless of literary genre, the Spanish encyclopedia separates authors of short stories, novels, poems, and essays, among others.

The next group is the most notable: 24 authors have articles in Quechua, but not in the Spanish version (see Table 1). In some cases, the absence from the Spanish Wikipedia is surprising, since they are intellectuals with influential publications and no strangers to academic recognition. As such, notability would not be a problem when creating their articles. This is the case for authors such as Jorge A. Lira, José Luis Ayala Olazával, William Hurtado de Mendoza, among others.[12] It means that the Quechua Wikipedia community has created an image of Peruvian literature that differs from the national literature in the Spanish version. Moreover, the community does not seek to translate its proposal into Spanish: Quechua-speaking users write for other Quechua-speaking users.

In academic studies on Peruvian literature, translating Quechua literature to bring it closer to the Spanish-speaking public is more common. In 1905, the same year that Riva-Agüero’s influential history was published, Tarmapap pachahuarainin appeared in Tarma, a small town in the Peruvian Andes. The author, Adolfo Vienrich, compiled poems and short stories in Quechua, and included an introduction and translations in Spanish. Jorge Basadre’s Literatura inca (1938), the first anthology of Quechua literature, applied the same strategy. Since that founding moment, no history of Peruvian literature has been written in a language other than Spanish.[13] In this context, the Quechua Wikipedia is a fundamental resource, as users interact within this space to write their own narrative about Peruvian literature and propose alternatives to the idea of national literature created in the Spanish-speaking academic field.

It is not only that each community pursues its own goals when including and excluding writers in a national literature. The use of different languages implies ways of narrating that necessarily vary, as is the case with Spanish and Quechua. In that sense, Wikipedia allows for the comparison of two languages working to achieve the same purpose: to introduce the life, works and cultural value of authors to a non-academic public. In other words, the image of a national literature changes due to the lists of Peruvian writers and the particularities of the language.[14]

Table 2 shows the 20 most prominent words in both Wikipedias. To determine them, I converted all entries from the Spanish and Quechua Wikipedia into literary data (a dataframe with two columns: all words and the number of times they were used) using Rstudio. In the case of the Spanish version, I removed stopwords such as prepositions or articles. Table 2 reveals similarities between the Spanish and Quechua version due to the nature of the encyclopedia. Thus, the words that stand out are those related to the date of birth, such as year (“año”, “años”, “watapi”) or month ("killapi); place of birth (“perú”, “piruw”, “lima”); and education (“estudios”, “colegio”). In the latter case, the National University of San Marcos, the oldest university in the country with its foundation in 1551, has a privileged position, since several words that are part of the institution name appear in both lists: “Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos” and “Mama Llaqtap San Markus Kuraq Yachay Sunturnin”. Many Peruvian writers are linked to the university, either as students or professors. On the Quechua version there are more words for biographical purposes, for example, birth (“paqarisqa”) or name (“sutiyuq”). As mentioned above, it is common for this Wikipedia to present only a brief biography and a list of works.

On the other hand, the differences between the two lists show that the languages emphasize different aspects when constructing the idea of a national literature. In Spanish, the country as a totality is fundamental. Therefore, “perú” is the word in the first position and its adjectives are also present (“peruano” and “peruana”) along with “nacional”. In contrast, Quechua privileges the relationship with smaller geographic spaces, such as cities and towns: the word “llaqtapi” is in second place and it specifically means “in the town”. The fact that “lima” is more frequent than “piruw” confirms that the cities where writers are born are more important than the whole country in the Quechua Wikipedia. Similarly, the Spanish version includes a set of words referring to the writing and publication of texts: work, literature, book, writer, and journal (“obra”, “literatura”, “libro”, “escritor”, and “revista”). The list even includes the literary genre of greatest relevance with the words “poeta” and “poesía.” In Quechua, the articles offer a different perspective: instead of focusing on those aspects, language is the main factor in describing the writers. Thus, there is a concern to clarify whether the authors write in Spanish (“kastilla simipi”), Quechua (“qhichwa”), or both. Of course, in Spanish, the articles do not make this clarification because it is assumed that Spanish is the default language of Peruvian literature. For this reason, Quechua Wikipedia pages develop strategies of resistance that acknowledge its importance in the national culture.

The Wikipedias in Spanish and Quechua reveal two communities with specific LPOV’s that use the platform to propose different narratives of Peruvian literature. In that sense, they are independent systems that work under their own logic. For example, a user of the encyclopedia will find that the versions present lists of writers that differ. The user will also notice that each Wikipedia has its own most prominent writer, who represents the values of the community: Mario Vargas Llosa, whose novels in Spanish won him a Nobel Prize, and Jose María Arguedas, the main representative of Quechua influence in Peruvian literature.

Conclusion and Further Work

Research on inequality of digital representation usually uses a global approach, and focuses the gap between the Global North and Global South. The former works as a core with the power and ability to represent the latter, a periphery. However, this study preferred a local approach that shows the functioning of peripheries (the Amazonian regions and the Quechua language) within the periphery (Peru).

This paper reveals that, while some zones reflect traditional views of a national literature, Wikipedia also permits a challenge to the construction of Peruvian literature in the Spanish-speaking field. Both the Spanish and Quechua versions reduce the cultural diversity of the country by constructing a national literature that ignores the contribution of the Amazonian regions. This reproduces the approach in academic criticism that oscillated between the coast and the Andes when defining the national literature. At the same time, because of Wikipedia’s accessible and collaborative nature, the encyclopedia enhances the participation of diverse communities in constructing a national literary tradition. The encyclopedia in Quechua is a notable example, since it constitutes a foundational moment in the construction of a national literature written by Quechua-speakers for Quechua-speakers. This tension between tradition and innovation within Wikipedia coincides with the results of the research on Google and the canon of Dutch literature: “While Google’s representation of literary canonicity partly depends on that tradition, we can now establish that the Web also enables new notions of literary importance” (Deijl, Smeets, and Bosch 28).

As a result, it is evident that there are still several issues to be addressed. The exploration of diversity on Wikipedia requires the study of another fundamental aspect: the representation of female writers (18.6% in the Spanish version; 14.3% in the Quechua version). Future academic work should explore the reasons for this gap and determine which women writers still do not have a Wikipedia page. Also, the issue of cultural diversity remains an open question. Research should also design a data collection process to identify the representation of Afro-Peruvian, Nisei, and Tusán writers (Peruvians with Japanese and Chinese ancestry, respectively), just to mention a few ethnic groups. It is also necessary to compare the two Wikipedia versions analyzed in this paper with the Aymara version, another indigenous Peruvian language.

In conjunction with these projects, the research shows the importance of working with local communities to close the gaps in Wikipedia. In other words, attracting different social groups to interact with Wikipedia is urgent. The number of visits and edits to the Quechua Wikipedia in November 2021 demonstrates that the community is not yet large enough and is basically located outside of Peru. More people are needed to create pages about Peruvian writers and explain their contribution to the national culture. In the same way, Wikipedia user communities in the Amazonian regions should be responsible for the inclusion of their writers in the encyclopedia, although those communities first need to be created. For this reason, a Public Humanities project with the power to mobilize cultural communities should be the next step in the process of writing and challenging the history of Peruvian literature in Wikipedia with a cultural diverse perspective.

Dataverse Repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SYHGNO

Peer reviewer: Evelin Heidel (Wikimedistas de Uruguay)

The Wikipedia article “Literatura del Perú” does include them as part of Peruvian literature. This entry is not part of the analysis because there is not a Quechua version. However, future research could compare the Peruvian authors in the article with the category “Escritores de Perú”.

Tumbes is another absent region in the category “Escritores de Perú”. This area is at the bottom of the Peruvian population and GDP ranking.

All the information about the percentage of Quechua speakers comes from the latest national census in 2017. See Andrade Ciudad

I am responsible for all the translations from Spanish to English.

Sánchez published the first volume of his history in 1928 and subsequent volumes appeared in the following years until the definitive edition of 1973.

About this dual perspective, see Nieto Degregori.

In the field of literary history, a pioneering work is Toro Montalvo, Historia de la Literatura Peruana. Literatura Amazónica (1996). Recent works include Gómez Landeo, Huamán Almirón, and Noriega Hoyos, Literatura amazónica peruana (2006); Marticorena Quintanilla, “Loreto en su literatura” (2007) and Proceso de la literatura amazónica peruana (2009); Villa Macias and Martínez Lizarzaburu, La literatura en Ucayali (2009); and Vírhuez, “La literatura en Iquitos” (2021).

There is not a single set of principles for measuring canonicity in the digital world. Hube et al. (18-19) proposes 5 ranking measures: page length, number of in-links, PageRank writers, PareRank complete, and number of page views. Blakesley (2) states that Wikipedia pageviews provides insight into synchronic canonicity. Deijl, Smeet, and Bosch (29) explain that the canonical status depends on the volume of searches on Google. Instead of a single factor, this research proposes that a canonical writer on Wikipedia is defined by the combination of at least two factors. This is a subject that still needs to be investigated.

This difference between prestige and popularity is partly based on Porter’s approach, even though he proposes that prestige is tied to the academy.

The most active editors and visitors to the Quechua Wikipedia are not located in Peru, but foreign countries (United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Germany, among others). Although my goal is researching about representation, but not participation on Wikipedia, it is worth mentioning that multilingualism and migration could constitute the defining features of this community. About the linguistic factor, researchers have already identified its importance in the formation of Wikipedia communities: “This study finds multilingual users are much more active than their single-edition (monolingual) counterparts … smaller-sized editions with fewer users have a higher percentage of multilingual users than larger-sized editions” (Hale) and Samoilenko et al. (“Linguistic Neighbourhoods” 16) state that bilingualism is one of the best explanations for the similarity of interests between cultural communities.

Wikipedia provides information about visits, not about unique visitors. A visitor can visit a Wikipedia page several times on the same day.

The 24 authors are an example of countercanon: “The countercanon is composed of the subaltern and « contestatory» voices of writers in languages less commonly taught and in minor literatures within great-power languages” (Damrosch 45).

James Higgins published A History of Peruvian Literature in 1981; the Spanish translation was published in 2006. Literary criticism in Quechua is rare in Peru. Some examples are Atuqpa Chupan, a journal with 7 issues, and Wankawillka (2013) by Pablo Landeo, where he reflects on the oral tradition. There is no text that attempts to reflect on national literature. The only work with this scope is the Quechua Wikipedia.

Quechua is a family of languages. However, the majority of articles on Wikipedia are written in Southern Quechua, a standard established by Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino in Quechua sureño. Diccionario unificado quechua-castellano, castellano-quechua (1994).

_according_to_total_number_of_wo.png)

_according_to_total_number_of_wo.png)

_according_to_total_views_and_to.png)

_according_to_total_number_of_wo.png)

_according_to_total_number_of_wo.png)

_according_to_total_views_and_to.png)