On the world’s largest social book-reviewing website, Goodreads, one of the words emphasized in users’ personal profiles is eclectic.[1] “I’m a very eclectic reader,” says a woman who has been reviewing about 40 books a year on the site since 2010. “My tastes are pretty eclectic,” says another longtime user, an “obsessive reader who spends the majority of the day reading books.” “I have very eclectic reading interests,” says a Ph.D. in English who has reviewed 1,800 books on Goodreads and rated nearly 3,000. It seems reasonable for such highly active readers to describe themselves this way. Their reading covers a certain range of books. But what sort, and how wide a range? Do they read short, easy books as well as long, complicated ones? Obscure books acquired through specialist dealers as well as bestsellers bought at Walmart? Books by men as well as by women? Books marketed for young people as well as for seniors? Books written in different languages or different centuries, arising from different cultural contexts, centered on different themes? Surely every reader is eclectic in some of these ways and few readers in all of them.

If we want to distinguish between more and less eclectic readers, or, going further, to identify a class of people whose especially eclectic taste in reading sets them apart, how should we proceed? Can we trust that people who self-identify as eclectic readers really do read a wider variety of books than others? Or do such claims speak more to readers’ aspirational values and strategies of self-presentation than to their actual habits of reading? Using data from Goodreads to conduct empirical analysis of readers’ habits and tastes, we have found some answers to these questions.[2] But, as we will explain, our analysis has also revealed flaws in the very concept of eclecticism and particular difficulties in applying that concept to the practice of reading.

Eclecticism and the Sociology of Cultural Consumption

If you are a literary scholar, you may not be aware of the enormous body of work on the topic of eclecticism. Although it has been among the most central concerns in the sociology of culture for 30 years, little research has been done on the eclecticism of readers. The figure of the cultural eclectic was initially defined in relation to music listening. In a foundational article of 1992, Richard Peterson observed that classical music listeners were not as disdainful toward popular forms like rock and country as they had been a few decades earlier, and in fact often displayed keen enthusiasm for all sorts of music. Peterson posited a historical shift from highbrow snobbery, an exclusive taste for the best, most elite forms of culture, toward what he famously termed cultural omnivorousness. He further developed the “omnivore hypothesis” in a series of influential articles, and subsequent studies have variously confirmed, challenged, and refined his arguments.

Some scholars, following Peterson’s lead, define omnivorousness vertically, as an inclination to cross presumed boundaries between higher and lower cultural forms: a taste for opera but also for ABBA, or a love of European art films but also Hollywood blockbusters. Others define it horizontally, as a measure of the sheer breadth and diversity of consumption: attendance at art museums and jazz concerts and local theater, plus a lot of podcasts and occasional evenings watching quality TV. There has been debate as well over the social implications of omnivorousness. On the one hand, the new eclecticism seems to some researchers to signal a more open, shared, and tolerant field of cultural consumption on which an earlier schema of high vs. low, with its implicit relations of status and stigma, has largely been superseded and democratized.[3] But other researchers emphasize that conspicuous eclecticism itself may be functioning, as Michéle Ollivier and Viviana Fridman put it, as “a new type of cultural capital, . . . a set of cultural attitudes widely considered as desirable but whose conditions of appropriation are unequally distributed” (9).[4] Seen in this light, eclectic consumers distinguish themselves socially by embracing multiple forms of culture that, to those with more ordinary tastes, appear mutually repellant. The eclectic’s unusually broad-spectrum tolerance functions as a weapon of social exclusion.

Research into these matters encompasses hundreds of articles and papers. As Hazir and Warde remark in an overview of the literature, the omnivore debate has become “an obligatory point of passage for empirical studies in cultural sociology,” an unavoidable crux for any scholar who sets out “to map taste and participation” (77). But in all this scholarship there is little analysis of readers as such and their specific tastes in reading. “Although notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ in literature have, as in other fields, . . . [undergone] transformations,” remark Bennett et al. in Culture, Class, Distinction, “reading has been marginal to the development of the thesis of the omnivore” (96). Where reading is considered at all, it is generally viewed in relation to other cultural activities, with readers’ eclecticism measured by the range and diversity of their cultural consumption beyond reading. From this perspective, people who like to read books do generally appear to be cultural omnivores, as well as to occupy relatively advantaged, more cultured or educated positions, positions of higher status, in social space.[5] In a large-scale mapping of cultural consumption in Norway, for example, Flemmen et al. found that readers of almost every kind of book appear on the “capital-rich” half of their social map, and are clustered in the more culturally-rich part of that better endowed portion. Expressing this in Pierre Bourdieu’s terms, the authors observe that book-readers have a higher-than-average overall volume of capital, while the composition of their capital is weighted toward cultural rather than economic assets.[6] Flemmen et al. show persuasively that readers of science fiction, historical fiction, contemporary Norwegian fiction, foreign classics, and most other kinds of book share a common neighborhood in the space of Norwegian lifestyles: a neighborhood dense with cultural eclectics. But the analysis does not enable one to look into that neighborhood more closely to see, for instance, which of the people who are reading science fiction are also reading foreign classics and historical novels, or whether such specifically literary eclectics even exist.

This gap in the scholarship reflects a more general dearth of empirical work on contemporary readers and reading practices (English), a field of research long held back by literary specialists’ aversion to empirical method (Bode) and sociologists’ lack of relevant datasets (Bennett et al.). Lately, though, the field of empirical reader studies has shown signs of life (Murray). The expanding toolkit of digital humanities has helped to make computational and statistical approaches less alien to literary studies, while the rise of social media platforms geared to booklovers (Goodreads, LibraryThing, StoryGraph, Wattpad) has made new kinds of data about contemporary readers and reading available at scale via web-scraping. At the same time, the increased visibility and influence of amateur book reviewers on Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok have made scholars more conscious of how little they know or understand about non-academic readers. Recent years have witnessed a burst of innovative empirical research into the way online platforms are shaping and being shaped by these amateur (and sometimes quasi-professional) literary critics. Melanie Walsh and Maria Antoniak have examined the genre systems developed by users deploying the tagging system of Goodreads and, in another piece with David Mimno, on LibraryThing. Alison Hegel has explored the differences between professional reviews and those created by online amateurs. Nika Mavrody et al. have traced the deployment of the concept of authorial voice in “vernacular criticism” that includes resources like Goodreads. As a result of these developments, it now seems possible for literary scholars finally to contribute something to the vast literature on cultural eclecticism and to bring the figure of the eclectic reader into sharper focus.

Goodreads, a site where hundreds of thousands of highly active readers have been depositing information about their habits and preferences for over a decade, remains an especially enticing target for data-hungry researchers in the contact zone between literary studies and the sociology of cultural consumption.[7] Goodreads users are not representative of the entire population of book readers. No one knows what that population might look like if we had worldwide, multilingual data on every sort of reader and readerly practice. But Goodreads appears to tilt strongly toward Anglophone readers and to overrepresent readers based in the US.[8] Additionally, Goodreads data provides only partial and distorted glimpses into its users’ reading activity. Many users downplay some of their tastes and preferences while highlighting others, and their strategies of consumption and presentation are shaped in part by the affordances of the site itself. Users seeking to become highly visible on the site may be guided toward expressing effusively positive responses to the books they review rather than providing their honest appraisals. Or they may join in on the collective review-bombing of a controversial book they have not actually read. Users who are authors themselves have been known to use fake accounts to promote their own work and/or to attack the work of others (Zarolli). But similar problems of sample bias, distortions in self-reporting, hidden dimensions of cultural life, and so on, plague any project of empirical research on cultural consumption. Despite its limitations, Goodreads is one of the best sources of data we have for developing methods to describe and measure readerly eclecticism, and to consider some of this concept’s ambiguous and puzzling dimensions.

Genres in Goodreads

Cultural eclecticism can only be defined and measured in relation to some specified set of cultural categories. In principle, these categories may be based on any axis of differentiation, whether between different media of production (painting vs. music vs. drama vs. literature) or different sites and modes of consumption (in large public places vs. small gatherings of family and friends vs by oneself at home), or something else. But for scholarship in this area, the axis of choice has always been genre. Peterson and his colleagues based their early findings on patterns of taste in music because that was the only field of cultural consumption for which their source, the NEA-sponsored Surveys of Public Participation in the Arts (Robinson), provided fine-grained data on genre preferences. With respect to reading, respondents to the NEA surveys were simply asked whether they read any “literature” at all—or, in later years, any “plays, poems, novels, or short stories” (1992). To define their musical preferences, on the other hand, they were asked to select the specific kinds of music they liked from a list of up to twenty different genres, including “easy listening,” “bluegrass,” and “big band.” Up to twenty because the list changed from one survey to the next: “soul” was separated from “blues/R&B” in 1992, for example, and “rap,” “reggae,” and “Latin/salsa” were added that same year. Such adjustments are necessary because, as we know, genres come and go; they bleed together and hybridize, or nest inside each other. There is no definitive set of genre categories and no definitive way to determine which works belong in which category. Different people treat different features as decisive, or employ entirely different taxonomies, depending on their situations, desires, and governing horizons of expectation. As John Frow remarks, genre is “a dynamic process rather than a set of stable rules.”

The indeterminacy of genre poses a challenge to the task of operationalizing eclecticism. In the absence of stable consensus regarding categories, features, and criteria of belonging, how do we decide whether, say, Liane Moriarty’s bestselling novel about a middle-class woman who thinks her husband may have killed someone, The Husband’s Secret (2013), is a thriller, a mystery, a romance, literary fiction, chick lit, or something else? And if we can’t reliably decide that, how can we say whether or not, for a given reader, Moriarty’s novel contributes to a pattern of varied and wide-ranging taste in fiction? Goodreads offers a possible solution to this difficulty insofar as genre on the site is determined democratically. Each reader of a given book may assign it to one or more shelves in their Goodreads collection, based on whatever array of shelves and shelf-names they like. When you first create a Goodreads user account, there are a few default shelves to get you started (“want-to-read,” “currently-reading”). These are not genres, and there is no built-in system of Goodreads-preferred genre categories or nomenclature. If you start to add a new shelf for “espionage fiction,” Goodreads is not going suggest “spy novel” instead. The choice is yours, with the result that some readers’ shelf systems appear highly idiosyncratic, involving genre categories such as “semi-rural” fiction or “feelings-of-love” novels. As Hegel observes, “When amateur and professional readers talk about genre . . . they’re not talking about the same thing” (36).[9] But the aggregation of all shelf assignments made by all users brings more familiar categories to the fore as well, yielding crowd-sourced data that can be used to quantify a book’s perceived generic profile. In the case of The Husband’s Secret, the top ten user-assigned shelves as reported on its Goodreads landing page are: fiction (4,270 users), mystery (1,551), chick lit (1,054), contemporary (1,000), audiobook (779), adult (529), contemporary-fiction (450), thriller (480), mystery-thriller (434), and book-club (374).

These data confront us with many choices. Can we safely ignore categories like fiction, contemporary, and book-club as irrelevant to matters of genre? Or are the data pointing to a generic space populated by works of contemporary book-club fiction?[10] How far should we go to consolidate closely-related shelves by merging them into larger categories? We might agree on always bundling mystery-thriller together with mystery and with thriller, but if suspense is present, should we include that as well? Or does suspense belong in a separate category, perhaps along with horror and/or fantasy? Regardless of how we handle such questions, the data yield a set of ratios. Instead of simply counting The Husband’s Secret as a thriller—the label assigned to it by its publishers and by Wikipedia—shelving data asks us to count it as approximately equal parts mystery/thriller and contemporary/chick-lit.[11] Parceled out this way, Moriarty’s putative thriller registers as a quantifiably more eclectic choice in the collection of a user who favors historical romance or young adult fiction than in the collection of a user who favors chick lit or detective fiction. The point is that by using the shelf-weights assigned collectively by reviewers on Goodreads, we can capture genre as it occurs in the dynamics of social practice rather than as a set of distinct types anchored to formal textual features (a method favored in computational studies) or to institutional taxonomies such as library catalogs or publishing industry marketing categories (a familiar approach in book history).

Two Ways of Measuring Eclecticism: Average Distance vs. Shannon Diversity Index

When we began gathering data for this project in the fall of 2021, Goodreads claimed that it had 75 million registered users. The site assigns every user a unique identification number visible in the URL for their user page. Most of these accounts are dormant. Most of the non-dormant accounts contain fewer than five reviews. For the purposes of studying eclecticism, we needed to select a set of readers who have deposited much more information than that about what they like to read. We settled on a minimum of 150 reviews as the criterion for inclusion in our study, defining these as Goodreads’ “highly active” users. To gather an unweighted sample of those users, we generated random numbers between 1 and 130,000,000 (in our observation, the approximate range of Goodreads ID numbers at that time), checked each one to see if it was associated with a user (about half of all numbers were unassigned), and recorded how many reviews the user had produced to that point. As we expected, only a small fraction, about 0.2%, had published more than 150 reviews—though that suggests the site has at least 150,000 such users, an impressively large number of avid, mostly long-term readers. We continued the process of randomized user searching until we gathered 3,209 of these users, roughly 2% of all those who met our criterion.

Between them, the users in our sample have placed some 885,000 unique books into their collections. About 600,000 of those books have been shelved by enough users for Goodreads to report data about their genre that we can use in a network analysis. When we construct a network based on the top ten genre-shelf assignments of all these books and run a community-detection analysis, we find eight main clusters or neighborhoods, which we have labelled children’s, fantasy/SciFi, graphic, historical, literary, mystery/thriller, nonfiction, and romance.[12] The top ten shelves in each of these clusters are shown in Table 1.

Based on how many of a book’s readers shelved it somewhere in each of these genre-clusters, we can compute the relative frequency or “shelf score” of that genre for that book. A simple example is Gillian Flynn’s 2012 blockbuster Gone Girl, which has a mystery/thriller shelf score of .83, a romance score of .17, and a score of 0 in the other six genres. One way that we can use this data to measure a reader’s eclecticism is to calculate the average distance between the books they’ve read. We can imagine a graph where the X axis shows a book’s romance score and the Y axis shows its mystery/thriller score. Based on Goodreads shelves, the Sue Grafton mystery novel A is for Alibi, which scores nearly 100% mystery, is about as distant as it is possible to be on this graph from the erotic romance 50 Shades of Grey, which scores 100% romance. Delia Owens’s bestseller Where the Crawdads Sing, which has moderate shelf scores for both mystery and romance, is positioned somewhere between the two, closer to each of them than they are to each other. If we make a more elaborate graph, with eight axes corresponding to the eight genre clusters identified above (impossible to picture but easy to construct mathematically), we can use the shelf scores of each book to locate it in all eight dimensions. When we plot all of a user’s books this way, we can calculate the distance between every possible pair of their books in this eight-dimensional space.[13] We can then determine for every reader the average pairwise distance between books in their Goodreads library. Because “average pairwise distance” is something of a mouthful (and sometimes we are interested in the average average pairwise distance for a group of readers), we refer to this simply as the reader’s “Distance Score.” This metric gives us a rough sense of whether a reader tends to read lots of books that (according to the collective shelving decisions of Goodreads users) look like each other, or on the contrary chooses books that occupy distant corners of the genre space.

Something to bear in mind about this metric is that a reader who has read all three books just mentioned will have a lower Distance Score than a reader who has only read A is for Alibi and 50 Shades, even though their reading extends in both cases across the same maximum mystery-romance range. A different approach, which would count these users as equally eclectic, is to measure eclecticism using something called Shannon diversity. Widely used in studies of ecosystems and population genetics but a novel approach in the study of cultural consumption, the Shannon diversity index is a metric that attempts to gauge both the variety of categories in a set (the number of different kinds of thing) and the balance of things across the categories (the number of examples of each thing).[14] In Figure 1, Reader A has read lots of Romance (in orange), some fantasy (in pink), and a little mystery (in yellow). This leads to a fairly low Shannon score of .687—low in this context, it should be said, since Shannon scores vary in magnitude depending on how many categories you’re measuring. Reader A can improve their Shannon score in two ways. They can read more of one of the genres in their small pie slices. In that case, they’d be like Reader B, whose reading is more balanced because of their greater mystery consumption, giving them a Shannon score of .997. Or they can do some reading in a new genre, like Reader C, whose enjoyment of graphic novels (in red) gives them a Shannon score of .930, even though they read the other genres at the same rate as Reader A. The most eclectic reader by this metric in our system of eight genres is Reader D, whose perfect balance among all the genres gives them a score of 2.08.

Reaching the optimal score of Reader D is quite unlikely under real world conditions, not least because individual books often belong to multiple genres. Among our users, the average Shannon diversity score is 1.4.[15] The standard deviation is 0.4, meaning two-thirds of users have scores between 1 and 1.8. At the extreme ends of the scale for our 3,209 users, there is one with a score of 0 (all their books belong to the same genre) and two whose scores exceed 2.0 (their books are almost perfectly balanced among the eight genre clusters).

Figure 2 is a plot of our users by Distance Score (on the x axis) and Shannon Score (on the y axis). The sloping fit line tells us that the two figures are quite closely correlated. (In a linear regression, r2 = .87 and p < .0001.) That makes sense, since we used the same genre/shelf information to calculate them. Nevertheless, the two metrics still create meaningful space between our readers, and from this plot, a few generalizations can be drawn about the most and least eclectic users in our study. In the southwest quadrant, at the very low end of both the Shannon and Distance scales, we find a preponderance of readers (colored orange) whose most favored genre is romance (Figure 3). At the opposite, northeast corner of the scales, we see comparatively few romance readers, and a high fraction of the readers who favor literary fiction (green). Overall, as presented in Table 2, romance readers collectively have the lowest Distance Scores and the lowest Shannon Scores, while readers who favor literary fiction score the highest on Shannon and the second highest on Distance, just slightly behind readers of mystery/thriller.

This is as we might have expected. The numbers affirm an established cultural hierarchy of genres, with romance novels positioned “low” and literary fiction “high,” as well as an established hierarchy of readers, with literary fiction readers showing up as less “common” than romance readers (nearly seven times rarer in our dataset), and less “simple” (inasmuch as their 60% higher Shannon scores express greater complexity in the composition of their libraries, greater sophistication in the sense of a purposeful mixture or blending). Our analysis also accords with reasonable assumptions about education and access. Generally speaking, works of literary fiction are measurably more difficult than other genres, more challenging in their syntax and vocabulary and narrative form, demanding more education and literary training. We can assume that a reader who has been provided with sufficient educational capital to enjoy and appreciate the work of esteemed literary fiction writers like Toni Morrison or David Foster Wallace can make sense of a popular romance by Nora Roberts or John Green, but we cannot assume the reverse. And only readers who are trained to enjoy the most difficult, least accessible genre, can approach maximum eclecticism as measured on the Shannon scale.

On the other hand, the fact that readers of literary fiction have access to every genre does not necessarily mean that that they are interested in every genre. We can as easily imagine someone who reads nothing but literary fiction—a classic “univore” or literary snob—as someone who reads nothing but romance novels. But remember that our method involves classifying books according to the relative weight of the different genre clusters with which Goodreads users associate them. Very few books in our dataset are counted as 100% literary fiction, a category that intersects to varying degrees with all the others. If Ian McEwan’s critically acclaimed metafictional novel Atonement or Jane Austen’s classic Pride and Prejudice is in your collection, then you have read not just in the literary genre but also in historical fiction and romance. Based on this way of counting, it would be very difficult for a devoted reader of literary fiction to achieve a low Shannon score—and, in fact, only one of the 97 readers we’ve identified as favoring literary fiction scores as low on the Shannon scale as an average romance reader.

Eclecticism Over Time

As modeled in Figure 2, eclecticism has no temporality. Our calculation of a reader’s Shannon index or average pairwise distance is based on the data of their entire Goodreads library, with no regard to which books were added when. This is standard procedure in studies of cultural eclecticism, which typically ignore the temporal dimensions of consumption and preference, treating an individual’s taste as constant.[16] But after all, reading books takes time. At any given moment, we are all univores, reading just a single (kind of) book. The eclecticism of our tastes can only manifest over some span of time, and depending on how long or short a span is considered, our taste profile may look quite different. The average user in our database has built their collection over the course of about nine years. We can imagine that decade involving several distinct phases of reading: a YA fantasy phase, a Chick Lit phase, a female detective phase, an historical mystery phase. Figure 2 registers no difference between a user like that, whose eclecticism results from a pattern of serial univorousness, and one who is eclectic all along and might at any time be reading just about anything.

To investigate the temporal dimensions of eclecticism, we divided users’ reading into twenty equal time segments and examined the mix of genre-clusters in each segment. One of the first things we see using this approach is that most users add a disproportionate share of literary fiction to their collections in just the first two segments.

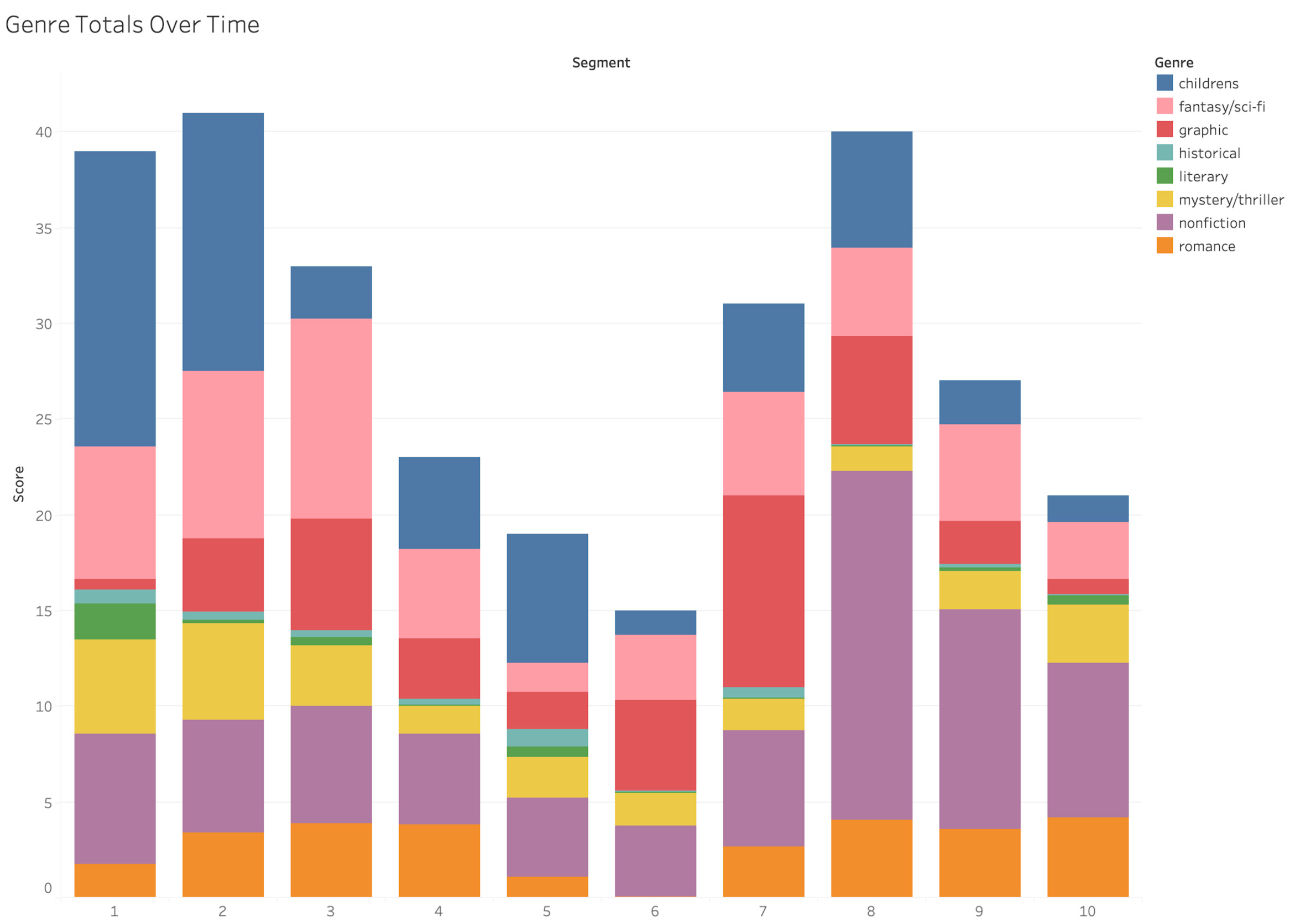

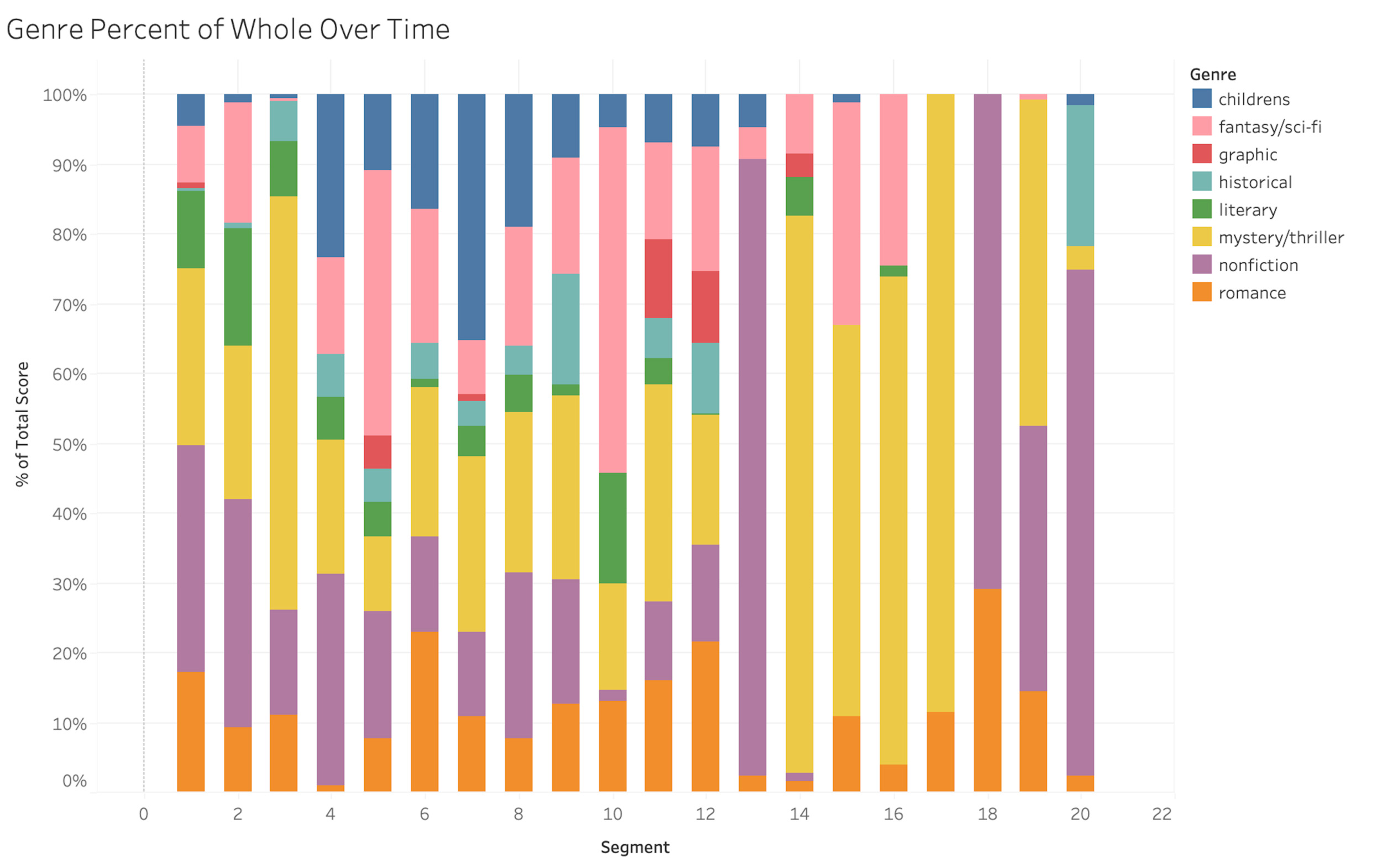

The upper image of Figure 4 shows the time-segmented data aggregated for all users as a stacked bar chart. As we see in the lower image, works of literary fiction (green), comprise 7.4% of the books in segment 1, which is sixty percent higher than the mean value of 4.6% in the remaining segments. Readers add more literary fiction to their collections in that first segment than they do historical fiction (teal) or children’s fiction (dark blue), genres that represent a larger share than literary fiction for every other segment. Conversely, readers allocate proportionally fewer titles to romance in the first segment (about 16%) than they do later on (averaging about 24%). What seems to be happening is that when someone first creates an account on Goodreads, they populate the shelves of their collection with a set of books they’ve already read. And those books typically include the classic novels they read in school: To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, A Tale of Two Cities. Some of our users were still in school or college when they opened their Goodreads accounts, and may have been adding these books in real time rather than retroactively. But the result is the same: literary fiction appears at first to represent a significant slice of their reading, and it provides a boost to their overall eclecticism numbers, even if it has no obvious place in their subsequent taste profile. We can see this pattern clearly expressed in the time-segmented shelf totals of a user visualized in Figure 5. Active on Goodreads since 2012, this reader began her collection with The Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby, and Jane Eyre. More than half the books she added in the early months are classified as literary fiction, while romance comprised just 2% and nonfiction about 4%. These ratios are the opposite of her reading over the subsequent decade, which was 90% romance or nonfiction and less than 2% literary fiction.

Would it improve our model simply to exclude data from the first few months of every user’s account? Aside from the fact that it is generally not good practice to discard inconvenient data, we should be mindful of the difference between an avid mystery reader who has also read many literary classics and an avid mystery reader with no such background. We found users whose literary fiction is almost entirely concentrated in the first segment of their collections but whose Favorite Books lists are stacked with books drawn from that segment. To them, at least, the earliest books seem to count for more, not less, than more recent ones within their overall taste profile.

But if some readers are strongly marked by the experience of reading classic literature in school, we found that literary fiction is not a “sticky” genre in terms of ongoing habits of reading. Most users who have early contact with classic and critically esteemed novels peel away from that kind of reading later on. Looking again at the upper image in Figure 4, we can see that the same is true for fantasy/science fiction, which drops from around 22% of the books read in the first few time segments down to 18% in the last few. Where do readers go, when they migrate away from those genres? Our data suggest that mystery/thriller is the stickiest of all major genre clusters. In the aggregate, readers tend to read more rather than less of it as the years go by.

Aggregated reader data like this does not tell the whole story about the temporality of taste. As pictured in Figure 4, the fraction of reading devoted to children’s literature appears constant at roughly 6.5% of users’ collections in every time segment. But when we look at data for individual readers, we see that this genre may be a negligible presence for years, then suddenly begin to claim a substantial share of a reader’s books—only to subside again a few years later. An example is seen in Figure 6, where a user who otherwise favors mystery/thrillers and nonfiction abruptly begins adding children’s books to her collection in time segment 4. From the specific books and her reviews of them, we know that a few years after launching her account on Goodreads, this reader began reading picture books to her pre-school son. Her habit of reviewing books he liked (“Little Fellow more than once begged for another chapter . . . he was very engaged with the story”) continued through his early elementary-school years and then ended. Since then, her collection has been more focused than ever on mystery novels and her favored nonfiction subgenres of self-help and inspirational memoir.[17]

A Goodreads user like this one, who reviews the books she reads to her children at bedtime, will appear more eclectic according to our metrics than a user whose taste in adult books is exactly the same but who does not happen to read to children. It’s tempting to argue that the higher Shannon and Distance scores in the former case are a misleading distortion, since what they capture is the distance in taste between two types of reader (an adult and a child) rather than between two types of book encompassed by the taste preferences of a single reader. But why shouldn’t we treat the co-enjoyment of certain children’s books (and dislike of others) as a legitimate component of a reader’s taste, and her buying or borrowing, reading and reviewing, of those books as an important part of her cultural consumption? This may seem a minor question, but it in involves a fundamental dilemma of method regarding what to count as someone’s reading. Versions of the question might be raised about librarians who run after-school reading programs for kids, professors who look for popular recent fantasy titles to include on their first-year syllabi, or indeed anyone whose reading includes books they read for the sake of someone else or to fulfill an assigned or chosen role. Even members of book clubs could be included in this category, inasmuch as they complain about having to read books they don’t like because their fellow members chose them. Should this kind of reluctant or compulsory reading count toward eclecticism, or not?[18]

Sociologists of culture have been divided on how to handle this ambiguity in the eclecticism concept. According to one line of approach, eclecticism is simply a matter of what one consumes, the extent of one’s contact with or participation in different cultural forms.[19] If you report attending the symphony six times a year, that counts as a data point whether you go because you love classical music or because you are a caregiver to your elderly mother who loves classical music. But according to another major strain of work, dating back to the original studies of Peterson and Kern, eclecticism is a matter of deeply held preferences, ingrained dispositions of taste: the relevant survey question is not “how many and what kinds of concerts have you attended this year?” but “which of the following kinds of music do you like?”[20]

Neither of these methodologies really addresses the underlying problem, which is that differences between doing something regularly and having a taste for it are not always clear even to ourselves. We may frequently prefer to read or watch something we regard as aesthetically inferior rather than something we would embrace as a work of genius, for example. Lurking within this ambiguity in the eclecticism concept are slippages between cultural habit, cultural taste, and cultural capital or expertise. And these become much harder to ignore when we introduce the vector of time. The reader visualized in Figure 5 was taught in college to appreciate classic novels (cultural capital). Under Favorite Books, she still lists “classics” (cultural taste). But nearly all the novels she reads these days are romances; she hasn’t read even one work of literary fiction in the last five years (cultural habit).[21] How we measure and classify the breadth of her taste, where we locate her with respect to eclecticism, depends on a number of methodological choices, but not least on how we deal with the problem of time.

Self-Identified Eclectics

These uncertainties about what counts as genuinely eclectic reading return us to one of the questions we started with: are readers good judges of their own eclecticism? Are self-identified eclectics (a group that could include the authors and many readers of this article) actually more omnivorous than everybody else? Or do they tend to overestimate, perhaps aspirationally to exaggerate, the breadth of their tastes? We tagged a large sample of users in our dataset whose “Interests,” “Favorite Books,” or “About Me” fields either include the actual word eclecticism to describe their reading habits, or contain self-descriptive phrases such as “I read everything,” “I read every kind of book,” or “I just love reading, I’ll read the back of a cereal box.” When we compare the Shannon Scores and Distance Scores for these 147 readers to the metrics for all other readers (including self-identified univores, readers who declare their narrow devotion to one specific genre), we do find a statistically significant difference, with self-identified eclectics a little higher on average by both metrics (Figure 7, Table 3).

This suggests that, whatever their limitations, our eclecticism metrics accord pretty well with commonsense use of the term. But, as is often the case in digital humanities work, we can learn something by looking at the outliers. There are readers who self-identify as eclectics but whose eclecticism, by our measures, is well below average. An example is a longtime highly active user whose About Me field reads, “Love any kind of books. . . crazy about books.” She describes her Favorite Books as encompassing “almost all genres,” and under Interests she again declares her “love [for] any kind of books.” By our metrics, however, this reader is a clear-cut univore. Her books are shelved as 84% romance, yielding a Shannon Score of .629 and a Distance Score of .36, both well below the median scores even among other romance readers. Looking at the genre-distribution of her books over time (in this case using a visualization that displays the raw book counts for each of ten segments, color-striped according to genre-cluster weights), we can see the overwhelming strength of her preference for romance (Figure 8).[22] The only other major genre in the mix is mystery/thriller, reflecting a growing taste in recent years for novels shelved as thriller, suspense, or romantic suspense, and often involving alpha-male romantic heroes in military, police, or firefighting milieux.

Outliers like this one, whose low scores on both metrics belie their self-identification as eclectics, are disproportionately readers of contemporary romance. While there is room within any major genre for some readers to roam more widely than others, the exceptionally large scale and subgeneric modularity of the romance genre space (Porter et al. 2023) make it especially easy for readers who never step beyond its boundaries to see themselves as exploring an ambitious expanse of literary terrain. The self-identified eclectic visualized in Figure 8 does indeed read widely across the romance ecosystem, from popular YA romantasy mysteries like Jennifer Lynn Barnes’s Inheritance Games series and new-adult chick lit bestsellers like Ali Hazelwood’s The Love Hypothesis, to dark erotica like Monica James’s Bad Saint and K. Webster’s Dirty Ugly Toy. She reads sports romances such as R. Holmes’s baseball novel Off Season, and has consumed all three of the wholesome, rescue-dog themed romance novels in Elysia Whisler’s Dogwood County series. But she also enjoys variations on MFM romance (one female, multiple males), like Double Doctors by Candy Stone and Punishing Their Virgin by J. L. Beck. There is some basis for such a reader to call herself eclectic. Compared to most other readers she interacts with on Goodreads, she is more open to new authors and new twists on the love-story plot. But because our vernacular system of classification locates nearly the entire range of her reading within the space of just one genre cluster, our analysis finds her self-declared “love for any kind of books” to be highly misleading.

We can contrast the almost monochromatic field of this user’s segmented reading chart in Figure 8 with the vividly multicolored bar chart of another self-identified eclectic in Figure 9. In this case, the reader’s description of herself as someone who “love[s] reading just about anything” is strongly affirmed by our metrics, landing her as a red dot in the upper right corner rather than the lower left corner on the SIE scatterplot in Figure 7. But even this seemingly secure finding does not rest on bedrock. In choosing to measure eclecticism via genre diversity, we have followed standard practice in sociology of culture but ignored many other features of books that might be salient to consumers’ preferences. There is for example the language of publication. An avid audiobook listener who is trying to master Spanish as a second language might read books in multiple genres but only if they are available in high-quality Spanish-language audio editions—perhaps only if they were also originally written in that language. Or consider another potentially decisive feature: setting. An otherwise eclectic reader might mainly read novels set in the American South, while another is only interested in Anglophone novels set in East or Southeast Asia. Significantly constraining though they are, these kinds of taste filters do not register in genre-based metrics of eclecticism like ours.

In the case of the self-identified eclectic reader displayed in Figure 9, a key factor that is invisible to genre-based metrics is author demographics. To obtain that information, we need to go through a user’s books by hand and look for information about the authors elsewhere on the internet. That’s obviously not something we can do for all our users and the 800,000 unique books in their collections, but it’s possible when investigating individual readers. In this particular case, and allowing for the uncertainties and potential misrepresentations involved when assigning individuals to demographic categories based on information discovered online, we found that more than half of the books the reader has reviewed, including 60% of the books she shelved as romance and 80% of those she shelved as crime, were written by African American authors. Her most populated shelf by far is african-american, and that category grows even larger if combined with the shelf she calls africanamerican.

Like the self-declared eclectic who only reads contemporary romance, this is someone who, from one perspective, is perfectly justified in saying she reads “just about anything,” but who, from another perspective, appears to focus most of her reading within one part of the literary space—the space of African American book culture. There are other readers who are open to a variety of genres but read mainly books by Irish writers, or by Canadian ones. Heterogeneous though they are in many ways, these books define comparatively restricted sectors of the field, limiting the devoted reader to a tiny fraction as many works as would be found on the shelves of contemporary romance or any of the other major genres. In the case of African American literature, it is a sector that has long been systematically marginalized by the publishing industry.[23] But it is also a more prestigious sector than romance, punching far above its publishing-industry weight on recent prize lists, One Book programs, and academic syllabi.[24] The visualizations of Figures 8 and 9 thus capture how, in our eclecticism charts, consumers of more prestigious works tend to rise to the top. Using the best, most democratized literary genre data we know of, we have built a model of eclecticism that, like models of eclecticism constructed by sociologists of music, art, and other fields, affirms correlations between cultural eclecticism and cultural status. It credits readers who tend to stay within the boundaries of a small, high-prestige space with more open and adventurous taste than readers who roam widely around a giant, low-prestige space.

We don’t defend such a model as optimal, but nor do we reject it as improperly designed. Altering the metrics by, for example, differentially weighting temporal segments to lower the eclecticism scores of crime-fiction devotees who report having read lots of literary classics in college, or redefining “major” genre clusters to raise the eclecticism scores of people who read cowboy, hockey, urban, and paranormal subgenres of romance, would yield a different but not necessarily a more equitable or inclusive perspective on the question of who are the most open or tolerant readers. When we embarked on this project, we aimed to use data on readers and reading to operationalize literary eclecticism such that literary scholars could finally enter the debates ongoing in other fields regarding snobbery, status, and eclectic consumption. At this stage, we have mainly managed to unsettle some assumptions in those debates and to introduce some new complications of counting and classification to the old problem of how to measure breadth of taste. But if we have made that problem seem more daunting, we want also to make clear its relevance for a discipline that has come to an important crossroads with empirical method.

The point of all the work over the years on the omnivore hypothesis was always to arrive at a better "vision of divisions" on the fields of cultural practice (Bourdieu, “Social Space and Symbolic Power” 23). Grappling with readerly eclecticism is a way of discovering meaningful differences between readers. Two people who might both be called avid romance readers may differ sharply in the range of books that give them pleasure, and, no less important, in the books that bore or repel them. And those differences will say more about where they are positioned on the field of reading than their seemingly shared taste for the novels of Emily Henry. As long as literary scholars were content to base arguments about literary reception on comforting generalizations about “readers” who were no more than projections, idealizations, or figments of the discipline’s collective imaginary, there was no reason to bring these deep divisions to light. Andrew Piper recently demonstrated, via a sample of 3,000 sentences in which literary scholars invoke a reader or readers, just how overwhelmingly dominant that homogenizing approach has been.[25] We can rejoice in the signs of its gradual eclipse as the rise of online bookish activity and the routinization of web-scraping and other computational methods enable work in which claims about reading are supported with data on actual readers. But for this strain of research to fulfill its potential, it must truly break the bad habit of generalizing from reading as it is done in the academy, universalizing the dispositions of a powerful but restricted fraction of the reading class, or opposing that fraction to a hypostatized mass of “ordinary” readers in a simplistic binary scheme. When we wrestle with the imperfect concept of eclecticism and the many challenges of measuring it, we are pushed to develop subtler understandings of affinity and antagonism, better maps of the disparate communities of taste whose relations to one another shape the real world of book-reading.

Data Repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QHLDXA

Peer reviewers: Maria Antoniak, Melanie Walsh

For personal profiles, we scraped language from the “Interests,” “Favorite Books,” and “About Me” fields of users’ accounts. Although the user pages of readers we discuss or quote in this article are open to anyone logged into a Goodreads account, we have chosen not to identify users by name or Goodreads ID number in our published work, nor to include that information in the datasets shared through our repository.

Work on this project was conducted at the Price Lab for Digital Humanities, University of Pennsylvania. Research assistants were Ashna Yakoob, Angelina Eimannsberger, May Hathaway, Jin Kwon, and Curtis Sun.

Although Peterson at times emphasized the continuing role of cultural consumption in maintaining distinctions between higher and lower social strata, he described the rise of omnivorous consumers as involving more “mixing” of “people holding different tastes” and a concomitant decline in the use of “the arts as markers of exclusion” (Peterson and Kern 905). The rise of omnivorousness, he concluded, was a strong “indicator of the democratization of the arts” (Peterson and Rossman 312). For Friedman et al., the spread of more eclectic, curatorial dispositions toward culture may be seen as part of a “wider democratizing shift” that is tending to “invalidate, or at least threaten, Bourdieusian processes of cultural distinction” (2).

Ollivier elaborated the perspective of this 2002 paper in later articles such as “Revisiting Distinction” (2008) and “Cultural Classifications and Social Divisions” (2009).

It is a fundamental question in the sociology of culture whether, as Max Weber believed, hierarchies of status are “not necessarily linked” (and may even “stand in sharp opposition”) to those of class (186), or, as Pierre Bourdieu maintained, the former are homologies of the latter, with art and culture serving to mediate distinctions of class and reproduce them in euphemized form as distinctions of taste (Distinction). For a vigorous defense of the neo-Weberian position, see Chan and Goldthorpe.

This, for Bourdieu, locates readers in the “dominated fraction of the dominant class” (“The Intellectual Field” 145).

In addition to the examples already given, scholars who use data from Goodreads to study contemporary literary tastes and practices include Pianzola, So (“Reading”), Thelwall, and Thelwall and Kousha.

Rough estimates of the demographics of Goodreads traffic, based on data gathered by Quantcast, are available here: https://www.similarweb.com/website/goodreads.com/demographics. A peer reviewer of this article speculated that Goodreads data may also be subject to genre-bias, in particular to an over-representation of romance and fantasy readers. The shelving data reported in Table 1 certainly show that the top shelves in our romance and fantasy communities are used much more often than those in other genre communities. Users shelved their books as “contemporary romance” five times as often as they did “literary fiction,” for example, and even “paranormal romance” (a minor shelf in the fantasy community) is used more often than “classics.” As discussed by Porter et al., Goodreads shelf data imply that romance is not just one genre among others, but “a juggernaut. . . a veritable genre ecosystem in its own right.” But we lack any sound basis of comparison for saying how far these statistical findings reflect a bias in Goodreads, versus how far they reflect actual popular tastes and/or popular classification habits.

Antoniak, Walsh, and Mimno reach a similar conclusion about the genre tags users deploy on LibraryThing, where “genre blossoms into an expansive grassroots literary taxonomy that incorporates familiar genres but also splinters into new forms that incorporate reviewer preferences and expectations” (29:2).

The presence here of audiobook (which Goodreads counts as a genre) might be explained by the conjecture that, although only a small fraction of books are published in audiobook format, those that succeed as book club selections are virtually guaranteed an audiobook edition.

Publishers and retailers classify books using the subject descriptors of the BISAC (Book Industry Standards and Communications) system. The Husband’s Secret is assigned the BISAC code FIC031080 as a Thriller / Psychological. There is no BISAC code for Thriller / Romance, although there is one for Romance / Suspense (FIC027110).

The community detection algorithm tries to detect communities of Goodreads shelves based on densities of the connections between them. Connections are dense among shelves that frequently appear in the shelf-data of the same book, as is the case for the shelves crime, mystery-crime, mystery-thriller, thriller, and crime-thriller. This kind of analysis depends on the specific algorithm being used. We used the Louvain method, which produces non-deterministic results, i.e. results that change somewhat every time one runs the algorithm (Blondel et al. 2008). How many distinct communities are detected varies with the granularity of the analysis. If we set the algorithm at a lower granularity, it tends to divide the network into just three communities: fiction, nonfiction, and romance. If we run the analysis at a very high granularity, a myriad of subgenres appears (religious, ghosts), displaying little stability from one run of the algorithm to the next. We settled on the detection of eight communities because at that level we get consistent outputs, and the important categories we call literary, mystery, and historical pop out from a larger community we call fiction.

We used Euclidean distance in these calculations. Readers familiar with text mining may be more familiar with cosine distance, which does a better job of handling the kinds of widely disparate magnitudes common in word distributions. In our case, however, all figures were normalized, meaning a reader’s distribution across genre clusters always sums to zero or one. Given that “Euclidean distance and cosine are in a bijective functional relation if Euclidean distance is computed on vectors that have been normalized to length 1” (Baroni et al. 252), we felt that Euclidean distance (the default measure in Python’s spatial library, and intuitive to readers with high school geometry) was appropriate.

The equation for Shannon diversity, sometimes demarcated as H’, is H’=−∑Pi ln(Pi), where “pi is the proportion of individuals belonging to species i” (Morris et al.), or, in our case, the proportion of a reader’s books allocated to each genre cluster. The Shannon index is a widely-accepted tool for measuring variety and balance (Nagendra 178). The one other factor often used in metrics of diversity is disparity (Leydesdorff et al. 257), which captures the degree of similarity between categories in the set. The idea is that readers of romance novels can increase their diversity more by reading a very different genre (say, opera librettos) than by reading a pretty similar genre (say, cozy mysteries). At present, there is no widely-accepted metric for uniting all three components (Leydesdorff et al. 255). Moreover, variety and balance are easy to capture with one metric (the Shannon index requires no inputs beyond the number of examples in each observed category), whereas disparity must first be operationalized in some way. In our case, it would require some way to say how different any genre is from any other genre. We could do this by various means—for instance, measuring how often our genre clusters co-occur in books—but these approaches are difficult to square with our literary critical intuitions. Is romance more distant from mystery or from historical fiction, given that the first two share features (e.g., both are defined by plot structures) whereas the first and third might share more readers (e.g. of regency romances)? Such questions are worth pursuing, but take us beyond the scope of this project. Given the intuitively legible results of the Shannon index and the complications of measuring and integrating disparity, we chose to stick with the Shannon index alone. It is worth noting, too, that no approach would resolve the problems with measuring eclecticism that we detail in the rest of this essay. These problems come down to inherent trade-offs that must be faced regardless of the chosen metric.

The numerical value of Shannon scores depends on the number of categories one is working with and the parameters one chooses when calculating the scores. Our analysis involves eight genres. We express a user’s balance among those genres in percentage terms, so that a user who has read 10 romances and 10 mysteries and nothing else will have a .5 in each genre. A user who has read 100 books in romance and 100 in mysteries and nothing else would have the same score. All users’ genre scores sum to 1, regardless of the absolute number of books each one has read.

An exception to the tendency to neglect temporality in empirical reader studies is Karl Berglund, Reading Audio Readers. Although he does not directly address the literature on eclecticism, Berglund reports a number of interesting findings about how reading is distributed across the hours of the day, the days of the week, and the seasons of the year. See Chapter 5, “The Reading Hours of the Day and Night: Temporal Reading.”

We would like to flag here a set of methodological and ethical questions that arise when scholars who study datasets scraped from online accounts begin describing individual users. As is pretty standard in this kind of DH work, our method involves shuttling between a) exploratory statistical analysis and visualization of aggregate data, and b) close examination of specific user cases. Here for example, we explored a rise-and-fall pattern in the reading of children’s literature over time by digging into the profiles of some specific users and mining personal details from their reviews. While our intention in highlighting one of these users in the discussion is simply to provide an example of a general phenomenon, and although we have withheld her account name and ID number (as we have done for all users in the datasets in our repository), we do specify her gender, quote her exact words, and mention unique aspects of her account. In this instance, we don’t feel that we are infringing on an individual’s privacy; the account profile is public and all the reviews have been published on the massive social platform of Goodreads.com. Nor does it seem to us that describing someone’s habit of reading aloud to their children is something that raises particular ethical concerns or requires special sensitivity on the part of a scholar. Still, this is an uncomfortably grey area in our approach. There are some users whose accounts we explored in detail, only to decide, during the peer review process at JCA, that we could not treat them in such a methodologically relaxed fashion. These include a small community of readers that we described as doubly minoritized—both socially, as Black women, and algorithmically, as users whose shared tastes in reading cast them as extreme outliers in the aggregated shelving data of Goodreads. Our attempt to describe this very small group of specific readers and their reading habits in terms of demographic features such as racial and gender identity and levels of education and income, began to drift from the methods of exploratory humanities data analysis into those of empirical social science research on human subjects: the kind of research that should obtain approval from an Institutional Review Board and adhere to the applicable federal (and international) rules on Protection of Human Subjects. A more recent Goodreads-based project at our lab did go through IRB, resulting in modified protocols regarding permissions, anonymization, security, and mandatory destruction of data. Such reviews will likely become a more usual stage of our workflow. The trouble is that, as humanists, we lack the training even to know when IRB should be involved. The relevant sections of the Code of Federal Regulations confront us with notoriously ambiguous terms and phrases. When, for example, does our analysis of a user account qualify as “obtaining information through intervention or interaction with the individual”? Are we interacting with them when we pull quotes from their account? When might our data be said to include “information that has been provided for specific purposes by an individual and that the individual can reasonably expect will not be made public”? Goodreads users obviously expect their reviews to be shared, but some hide their profiles from non-friends, and few if any would expect their accounts to be (in the language of the Code) “observed and recorded” by scholars or discussed in academic publications. As things stand, we are making too many ad hoc judgment calls. Perhaps it is time for scholars affiliated with JCA and digital humanities generally to compile a set of basic ground rules and best practices for the expanding wing of humanities research that uses data scraped from the web to study the attitudes and behaviors of actual “living individuals.”

The NEA surveys have dealt with this question by not counting books that were read “for school or work” (Robinson 1993).

That most researchers operationalize omnivorousness via consumption (practice) rather than taste (preference) is likely a reflection of the limited datasets available to them, especially for large-scale comparative analyses. See, for example, the various comparative studies of cultural consumption patterns in European countries, such as that of Virtanen, which are based on survey data collected by the European Opinion Research Group in 2001 (Christensen). As Virtanen acknowledges, a shortcoming of his and other such studies is that the underlying survey data, being focused on “broad categories [of consumption] such as going to the cinema,” cannot provide “information on what kind of movie one went to see” or, more generally, “on the actual content of individual taste repertoires” (243).

In their comparative study of musical and literary omnivorousness in Finland, Purhonen, Gronow, and Rahkonen argue for the superiority of this approach and the inadequacy of using consumption practices as a proxy for taste preferences.

As noted earlier, strictly speaking, all we know is that this user hasn’t reviewed any works of literary fiction on Goodreads during this span of years, or even added any to her Goodreads library. In saying that she hasn’t “read” any such books, we are ignoring the likelihood that her Goodreads library deviates to some extent from a perfectly accurate record of her reading. It is an open question whether other ways of gathering data on reading habits, such as survey methods or ethnographic interviews, are any less subject to unconscious biases, deliberate distortions, and simple errors of self-reporting. Social collection sites like Goodreads would seem to offer more protection against data skewed by faulty memory, but they may also encourage, through their promotion devices of competitive consumption and their various metrics of consumption and influence, misrepresentations aimed at burnishing an online profile.

We are visualizing the data in this alternative view because the books in this reader’s collection are distributed very unevenly over time and her preference for romance appears most starkly in the segments with the most books. If we used the same format as in Figures 6 to 9, the overall pattern would be obscured by the misleading visual equivalence of segments with 50 or 100 books and those with just a handful.

In Redlining Culture, his bracing “data history of racial inequality and postwar fiction,” Richard Jean So documents the U.S. publishing industry’s extreme underrepresentation of Black authors with respect to fiction, and especially to less prestigious but highly popular genres of fiction.

For example, five of the last twelve winners of the National Book Award for fiction have been African American writers. For analysis of trends in the distribution of literary prestige as regards writers of color, see Manshel, Writing Backwards, and Manshel and Walsh, “What 35 Years of Data Can Tell Us.”

Piper reports: “In my hand-annotated sample of more than 3,000 sentences, I did not find a single example where readers were invoked that was accompanied by any delimiting criteria…. In literary studies it appears that there are only imagined readers, who then slip unseen into our discourse as a form of evidence for our claims” (section III, p. 4).

_vs_shannon_score_(shannon_di.png)

_v.png)

__147_of_our_highly_active_goodreads_users_who_descri.png)

_vs_shannon_score_(shannon_di.png)

_v.png)

__147_of_our_highly_active_goodreads_users_who_descri.png)