Introduction

Western conceptions of the literature of the Global South, and of India in particular, have been powerfully shaped by the work of a small number of well-known authors writing in English. Not everyone has seen this as a problem. Salman Rushdie, for example, includes just one translated text (out of 32) in his influential collection of Indian writing Mirrorwork (1997), asserting in the introduction that “Indo-Anglian literature” is “proving to be a stronger and more important body of work than most of what has been produced in the 16 ‘official languages’ of India” (x). In scholarly circles, however, the distortions resulting from such a limited selection have come in for significant criticism. In Indian Literature and the World (2017), Rossella Ciocca and Neelam Srivastava criticize the “monolingual canon” of postcolonial literature, which “rarely includes Indian literature in English translation, and only considers a small body of texts written in English” (3), thus failing to adequately represent the multifarious preoccupations of Indian authors. Ciocca and Srivastava call for a new approach to contemporary Indian literature that foregrounds the role of translation as “central to the construction of a pan-Indian canon” (1).

The essays included in Ciocca and Srivastava’s volume can be understood as both an extension of—and a corrective to—a long-standing and still evolving line of inquiry in postcolonial studies. Here, the basic question concerns how a globalized, capitalist literary marketplace favors certain kinds of narratives and thus impinges upon the creative practice of those authors who seek to participate. Already in 1989, Timothy Brennan remarked on the distinctive features of works by non-Western authors who have achieved bestseller status. As he put it, “writers like Rushdie, Vargas Llosa and Allende” have achieved prominence in the West, “not because they are necessarily ‘better,’ but because they tell strange stories in familiar ways” (36). According to Brennan, such authors fulfill the “demands of Western tastes,” including the Western attraction to “writing that is aesthetically like us—that displays the complexities and subtleties of all ‘great art’” (36-37). Since the publication of Brennan’s work, a number of other scholars have taken up the question of what gets published and why. Graham Huggan, Sandra Ponzanesi, and Sarah Brouillette have all investigated what Ponzanesi refers to as a “booming otherness industry” (1) in which, in Huggan’s words, “difference is appreciated, but only in the terms of the beholder; diversity is translated and given a reassuringly familiar aesthetic cast” (27). More concretely, in addition to the characteristics adduced by Brennan, this Anglophone writing has been described as “possessed of a notably metropolitan or ‘hybrid’ consciousness” (Brouillette 8) as well as “relatively ‘sophisticated’ or ‘complex’ and often anti-realist,” “politically liberal and suspicious of nationalism,” and characterized by “a language of exile, hybridity, and ‘mongrel’ subjectivity” (61).

These discussions are based on the idea that works produced by the best-known non-Western authors are shaped in some way by their own positionality as well by their need to cater to an Anglo-European metropolitan audience. The perceived danger of the monolingual conception of the postcolonial canon is that it offers an incomplete, skewed, or overly accommodationist perspective on the culture and countries that it represents. A corollary of this position is that this same metropolitan audience would be confronted with a different, and perhaps more “authentic” representation of the countries and cultures for which these authors have been presumed to speak, if they were to encounter a broader swath of the writing produced by local authors writing in the indigenous languages of these countries or cultures.

Where Ciocca and Srivastava diverge from Huggan and others is in regard to the status of translation in their arguments. In the case of Indian Literature in the World, translations are opposed to an “Anglophone canon of texts,” that is to say, to the writing of a narrow group of prominent Indian authors publishing in English. Anglophone writing is therefore explicitly juxtaposed with a much broader group of works that originally appeared in one of India’s indigenous languages and which, when read in translation, might offer “a different picture of Indian writing than what is currently available today” (2). In the work of Huggan and those responding to him, one also finds criticism of the overwhelmingly Anglophone focus of the postcolonial canon, but there is little to no implication that translated texts might offer an interesting alternative to that canon. In fact, the two categories seem to be conflated. When Huggan, for example, refers to the “translated products” churned out by the “postcolonial field of production” (Postcolonial Exotic 4), he suggests that the homogenizing impact of the marketplace eliminates any meaningful distinction between English-originals and translations.[1]

There may be good reasons for adopting such a position. Pascale Casanova has described translation as “the foremost example of a particular type of consecration in the literary world” (133), implying that the very fact of translation means that a text has already assimilated itself to the hegemonic conceptions of what literature should be; translation is a way “to ‘discover’ nonnative writers who suit their (i.e. the hegemonic, ME) categories of the literary” (135). A distinct but related perspective by Rebecca Walkowitz in Born Translated (2015) explores how contemporary novelists approach translation as a “condition of their production” rather than as something that occurs only after publication. Writers such as Coetzee, Ishiguro, and Adam Thirwell (among many others) not only write with future translation in mind but incorporate translation into their novels in substantive ways, for example by presenting their own works as pseudotranslations, using multilingual characters and linguistic misunderstandings to structure the narrative, or weaving multiple languages into the storyline. Like Casanova, then, but from a more individualizing perspective, Walkowitz implies that an increasingly globalized market for international fiction has attenuated the distinction between “translations” and “originals.”

The following contribution seeks to intervene at precisely this point of divergence to shed light on a difference of opinion that has significant implications for both postcolonial studies and the study of world literature. On the basis of a computationally-assisted comparison of multiple corpora, we seek answers to two distinct but related questions: first, to what extent can the Anglophone works of prominent post-1945 Indian authors (the “postcolonial bestsellers” of our title) be seen to constitute a distinctive corpus vis-à-vis recently translated works originally written in South Asian languages; and second, whether the former group is characterized by features typical of Western literary fiction along the lines Brennan and others have suggested. For reasons that we will explain shortly, our control group for this second question comprises works translated from two European languages considered to possess high literary capital: French and German. By situating these postcolonial bestsellers within this broader context, we intend to provide a starting point from which to understand the differential pressures exerted by the “otherness industry” on literary production—as manifested in the texts themselves—as well as how the reception of South Asia might be different if Anglophone readers were exposed to a broader range of translated texts. To anticipate our conclusions, we find substantial alignment between our results and existing conceptions of the character of the postcolonial bestsellers, but we also find points of divergence that shed new light on the specific niche filled by the English-original texts and raise questions about the tradeoffs involved in a reorientation toward translations.[2]

Corpus

To situate postcolonial bestsellers within a global literary marketplace, we constructed four corpora for comparison. At the center of our analysis is a collection of 62 influential English-language texts written by prominent authors of South Asian descent. To compile this collection, we first surveyed available popular and scholarly sources to create a list of potential authors and texts whose work spanned the period from roughly 1950 to 2010. Within that time frame, we aimed to include at least a few texts from each decade, although the rising popularity of Indian literature since Salman Rushdie’s receipt of the Booker Prize in 1981 means that we had to grapple with a predominance of works published in the years since that date.[3] We also strove to include a mix of male and female writers.[4] Our primary popular point of reference was the list of “Greatest Indian Novels” published by the Hindustan Times and accessible on Goodreads. We also reviewed the shortlists for the Booker and the Commonwealth Writers Prizes and the Sahitya Akademi Award.[5] Scholarly resources included Salman Rushdie’s Mirrorwork: Fifty Years of Indian Writing 1947-1997, Priyamvada Gopal’s The Indian English Novel: History, Nation and Narration, and Ulka Anjaria’s A History of the Indian Novel in English. A certain degree of arbitrariness in the final collection was unavoidable, since inclusion ultimately had to be based on the availability of texts for digitizing. Most authors are represented by more than one work, usually by two or three, depending on how many texts were readily accessible.[6] In some cases, we were unable to obtain a copy of a specific prizewinning work by an author but found another work by that same author.

These practical challenges are the reason we settled for a total of 62 texts, a number whose only significance is as an indication of what we were able to assemble in a reasonable amount of time. Although not “representative” in a rigorous sense, our final collection contains a very plausible subset of the most influential English-language novels published by authors of South Asian descent in the past 60 years. Of the 33 unique authors whose books are included in the corpus, all but one author appears in at least one of the resources mentioned previously, and over 75% of these authors appear in two or more of the three categories of sources we considered (Goodreads, scholarship, and prizes). There are no doubt other works that would have been appropriate to include in the collection, but all of the authors in the corpus would be readily acknowledged as major figures in the South Asian literary field, and the list includes multiple works by authors frequently referenced in the scholarship of the field (e.g., Desai, Ghosh, Roy, Rushdie, Seth). A full list of the texts and the criteria used to justify their inclusion can be found on the data repository that accompanies the essay.

In order to evaluate the distinctiveness of our postcolonial bestsellers and to determine whether this distinctiveness aligns with Western literary conventions, we made use of three additional corpora. These are derived from a larger collection of translated fiction extracted from the HathiTrust Digital Library.[7] The metadata for the larger corpus includes information on original language for every text, and for the purposes of the current study, we created three separate collections of roughly equal size: one for translations from South Asian languages, one for translations from French, and one for translations from German. For the analysis described in this paper, we combined the French and German translations into a single comparison corpus of European literary fiction. As indicated in our discussion of results, however, there may be additional insights to be gleaned from further analyses in which the French and German texts are treated separately.

To compile these three collections, we first extracted all possible titles in each category from the larger Hathi corpus and then used random sampling to ensure that we had no more than five titles from any single author. We also took additional steps to eliminate titles that were written prior to 1950 but translated and published in subsequent years.[8] The discrepancies in the sizes of the three larger subcorpora result from the fact that the original corpus had a different number of texts from each language and a different distribution of authors within those languages. These curation efforts left us with 576 texts translated from South Asian languages, 500 texts translated from French, and 393 texts translated from German. The South Asian texts include works originally written in fourteen languages.[9] All but two of the postcolonial bestsellers and the majority of the texts in the other corpora are novels, although the South Asian translations corpus also includes a large number of short story collections. Table 1 provides an overview of the entire corpus:

Each of the original texts is represented by a 10,000-word chunk compiled from ten 1,000-word random samples. The sampling procedure allows us to compare texts of differing lengths without producing the distortions associated with some of our metrics, e.g. type-token ratio. We chose to focus on translations from European languages for two reasons. First, since the South Asian corpus consists entirely of translations, we wanted to control for any general effects of translation on the measurements we were using.[10] Moreover, using translations from French and German provided us with additional certainty that our control corpus reflects the “Western tastes” referred to by Brennan and others. These works not only appeared originally in European languages with high literary prestige but have also received an additional level of “consecration” by being translated into English for an English-speaking Anglophone readership.[11] If claims regarding the homogenizing effects of the global marketplace are correct, one would expect all three corpora (English-original, South Asian translations, and European translations) to reveal meaningful stylistic and thematic similarities.

Methods

The challenge was to choose analytical categories capable of identifying similarities or differences that are in fact meaningful, and also to operationalize these categories in a manner amenable to a computational approach. On the one hand, one can imagine features related to, say, plot, character, and setting, with regard to which the novels in our corpus would demonstrate a great deal of individual variety that in no way rules out the possibility of deeper commonalities. On the other hand, one can also imagine several stylistic or linguistic features that these novels would share but which are unlikely to shed any substantial light on our research question: references to foreign currency, for example, or the relative frequency of adverbs.

We settled on two critical concepts that have played a central role in scholarship on postcolonial authors writing in English: literariness and cosmopolitanism. Literariness and cosmopolitanism are complex phenomena, and our proxies represent only a tentative step toward identifying measurable features that make them tractable for an empirical analysis. However, inasmuch as we are interested in capturing features that might shape reception on a general level, then such broadly conceived and rather simple proxies suggest themselves as a plausible place to start. After all, as Amit Ray has written in a discussion of Huggan’s arguments, “naïve, de-contextualized consumption” is probably the default for all culture in the current, globally dispersed media ecosystem (130).

Literariness

Literariness has frequently been identified as a key distinguishing feature of postcolonial novels written in English. As Sarah Brouillette writes, “growing consensus holds that celebrated postcolonial writers are most often those who are literary in a way recognizable to cosmopolitan audiences accustomed to what Brennan identifies as the ‘complexities and subtleties’ of a very specific kind of ‘great art’” (59). To be sure, determining whether a particular text qualifies as (or is marketed as) “literary” entails more than a consideration of text-immanent features; nonetheless, such features have been the focus of the scholars with whom we engage, and we follow their lead here. We should also note that our use of literariness is not intended to imply that the “complexities and subtleties” appreciated by Western readers are more than a convention that has come to be viewed as a marker of prestige in some circles. We adopt it here simply to assess alleged parallels between English-language postcolonial fiction and other high-prestige fiction published in the Anglo-American context.

While any attempt to establish conclusively what it means for one text to be more literary than another is doomed to fail, there is an existing body of research in computational literary studies that adduces a set of possible criteria by which literariness can be measured (Cranenburgh et al. 625–50; Sopčák and Salgaro; Miall and Kuiken 327–341). We have chosen to focus on five: mean sentence length, type-token ratio, intra-textual variance, concreteness, and literary self-reference. The first measure is self-explanatory and can be understood as an indicator of textual complexity. Type-token ratio is a common measure of lexical variety, which we have selected under the (possibly controversial) assumption that vocabulary richness makes a text more literary.

Intra-textual variance measures the general level of lexical and semantic variation across a text. To calculate this variance, we first divided each of our texts into 500-word chunks. Then, we used the Top2Vec algorithm to embed our documents within a multidimensional vector space, in which each 500-word subsample (the original document is the sample) was assigned a series of coordinates (300 in this case) that provided the document with a unique location within that space. The vector space itself is produced by an embedding algorithm that makes use of the context of each word in the corpus; the resulting space turns out to represent some semantic relationships as spatial relationships. Once we had these vector coordinates, we calculated the centroid of the collection of subsamples derived from each document. Finally, intra-textual variance was determined by taking the sample variance of the Euclidean distance of each subsample from the centroid. This then became a measure of the semantic dispersion within the original document, under the assumption that semantic (and, by implication, thematic) diversity is an indicator of literariness. The intuition underlying this assumption is that high-prestige literary fiction is generally less internally homogeneous than, say, popular detective fiction or romance novels, two genres which tend to “closely follow established genre tropes” (Cranenburgh et al. 631). In this regard, intra-textual variance can be seen as related to type-token ratio (see Cranenburgh et al. 631–632).

Concreteness was determined using a dictionary-based approach, with Brysbaert’s “concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas” serving as our dictionary. In this case, our working hypothesis was that lower concreteness (higher abstraction) suggests a higher degree of literariness, since literary fiction includes more ideational and reflective content. We recognize that this claim is by no means self-evident; however, we felt that significant divergences in concreteness among the subcorpora in any direction would be notable and deserve further reflection, so we chose to include this measure even in the absence of complete certainty regarding its implications.[12] We use the term literary self-reference, finally, as a measure of how preoccupied a text is with literature itself. Our aim was not to capture those sophisticated examples of intertextuality and self-conscious narration that have come to be associated with postmodernist experimentation.[13] Instead, we sought to identify texts that included literary themes in a broader sense, under the assumption that literary fiction is often distinguished from other (genre) fiction in the degree to which it addresses, for example, writing, reading, authorship, other books, or the literary market. We determined literary self-reference using word embeddings generated by Top2Vec. The vector space was the same as described previously, but in this case, we made use of a different subset of the elements it contained, using cosine similarity to calculate the average distance for each subcorpus between the document vectors and the word vectors for a particular word of interest. The word vectors offered us a way of identifying a semantic field within the overall vector space. In the case of the term “literary,” for example, one of the terms we use for this calculation, the top terms appearing in closest proximity to it are “literature,” “writer,” “writers,” “novel,” “published,” “author,” “subject,” “publishing,” and “readers.” By calculating the distance of a given document from this semantic field, we can establish a rough sense of the thematic significance of the field to the document in question. In additional to “literary,” we also ran this analysis for the term “author.” In principle, one could select any number of terms as a baseline for this calculation. It is tempting—and, from a technical standpoint, very easy—to search for the term that will provide the ideal point in vector space from which to establish the degree of literary preoccupation that characterizes these texts. In our experience, however, word embeddings do not lend themselves to analyses at fine levels of granularity. Our goal was to capture a broad semantic space in which these texts participate, and we have thus opted to use the vectors for self-evident terms linked to our interests.

Cosmopolitanism

Situating works along the axis of cosmopolitanism also gives rise to challenges, especially given the multiple ways in which the term has been used previously. Sarah Brouillette’s reference to the “migrant or expatriate life” explored in these novels has already been alluded to (8). Brennan explains that the “cosmopolitans have found a special home . . . in the interplay of class and race, metropolis and periphery, ‘high’ and ‘low . . .’” (38). And Ponzanesi argues that in “becoming brand names, these writers contribute to a cosmopolitan culture of distinction, through which the consumption of postcolonial products is not just a sign of exoticism but also of worldliness and intercultural sophistication” (4).

Even on the basis of these few examples one can sees that cosmopolitanism is an overdetermined category, part of a larger conceptual force field that includes other vexed concepts such as hybridity, migration, metropolitanism, the global, commodification, and authenticity. Nonetheless, we believe that the category of cosmopolitanism provides a productive point of orientation for our analysis mainly due its strong connection to the urban and the international, both of which are amenable to quantification while still serving as plausible proxies for many of the elements that one would likely associate with the source concept.

We measure cosmopolitanism along five dimensions. The first dimension aggregates the number of times each document refers to one of the 500 largest world cities as ranked by 2023 population. From these document frequency counts, we then calculate the mean value for each subcorpus.[14] Our second dimension explores the broader geographical imagination of our corpus using named entity recognition. First, in a multi-step and hand-curated process, we identify and count all references to specific cities, countries, and continents in each document. In our version of this calculation, every reference to a city is also counted as a reference to the corresponding country or continent. We then calculate the Shannon Diversity Index (SDI) for each document at the level of country and continent (referred to as subregion in the results). Widely used in ecology, the SDI provides a value indicating the dispersion (or diversity) of countries and continents in the books in our corpus, in a manner that also accounts for the total population size (i.e. the total number of geolocations mentioned). In simple terms, SDI quantifies the likelihood that we will be able to predict the “species” (country or continent) of a geographical named entity taken at random from a specific text sample. A higher index value means a greater variety of geolocations, which we equate with a higher degree of internationalism or cosmopolitanism. To give a specific example, the sample from Chandrahas Choudhury’s Arzee the Dwarf (2009) only mentions India, giving it a country and a continent SDI of zero. By contrast, our sample from The Street Singers of Lucknow and Other Stories (2008), written by the Urdu novelist Qurratulain Hyder, mentions Pakistan, India, Austria, Israel, Syria, the United Kingdom, Japan, and several other countries, and thus has a country SDI of 2.58 and a continent SDI of .91.

Our three remaining dimensions are derived from word embeddings using the same vector space generated for the literary self-reference metrics. In this case, however, we chose to approach the topic ex negativo: we identify semantic fields that have typically been associated with the trope of “traditional society” rather than measuring cosmopolitanism directly. This decision was partly based on practical considerations—the most plausible candidates for direct measurement (e.g. “cosmopolitan” or “metropolis”) either appear too infrequently in the corpus to generate reliable results, or they appear in the vector space in close proximity to their opposing terms. For example, the word vector for “urban” also includes numerous terms linked to the semantic field of the rural.

Our primary reason for adopting this approach, however, was to add an additional layer to our analysis. Despite its ancient roots, the idea of cosmopolitanism is closely linked to influential discourses of modernity and modernization that have played an outsized role in stereotypical representations of the Global South, representations that have been criticized in the past decade.[15] Most notably, these representations have presumed a unified trajectory of historical development in which Europe embodies the features of a global modernity, whereas countries of the Global South are associated with an earlier (“pre-modern”) moment on the same timeline. This view finds expression in a range of influential arguments from the early twentieth century, including, but not limited to, Ferdinand Tönnies’ opposition between “community” and “society” and the folk-urban typology of Robert Redfield (Loomis and Mckinney 12–23).

Our effort to operationalize the category of cosmopolitanism ex negativo seeks to capture a few of the basic dichotomies that inform these typologies. We are interested in whether works translated from South Asian languages are more likely than the postcolonial bestsellers to reinforce associations between South Asian countries and the discursive features of an alleged pre-modernity: the foregrounding of village life, of kinship relations, and of the body, each of which has played a central role in the stereotyping of the Global South.[16] It is crucial to note in this context that we are not asking whether attention to these categories is an organic, essential feature of South Asian literature, but rather whether the exigencies of the global literary marketplace mean that works translated from South Asian languages engage with these categories in ways that are demonstrably different from those of texts translated from French and German or those written in English by authors of South Asian descent. If this turns out to be the case, we need to think about the trade-offs involved in a shift away from the dominance of these authors among Anglophone and European readers.

Our three scores based on word embeddings show the mean value for each subcorpus of the distance between the document vectors and the word vector of our chosen keyword. As in the case of our measures of literary self-reference, the challenge here is the infinite number of keywords that one could use: in the case of the body, for example, should the focus be on specific body parts (hands, heads, hearts), or perhaps on bodily processes (breathing, digestion)? As before, we opted for simple, frequently-occurring terms with a self-evident connection to our three areas of interest: “village,” “family,” and “body.” Table 2 shows the nine terms most-closely located to these root words in our model.

Results and Discussion

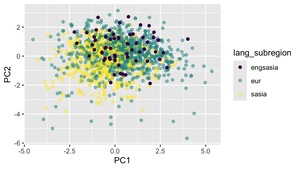

As a first step toward evaluating the distinctiveness and internal cohesion of these corpora, we use principal component analysis (PCA) to plot two-dimensional visualizations for literariness and cosmopolitanism. PCA allows us to take the six variables assigned to each document for each category and compress as much distinguishing information as possible from those variables into a new set of variables, called principal components. What allows for such a consolidation is the fact that some of the original variables may be correlated with each other, which means that some of the aggregate impact can be captured by a single component. The procedure uses linear algebra. If we had just two dimensions of correlated data along a diagonal, we can imagine rotating the data so that the widest part of the pattern is horizontal. PCA does this in higher dimensions. We are essentially rotating our six-dimensional data so that the first two dimensions show as much of the variation within the data as is possible in just two dimensions. Figures 1 and 2 show the relative positions of the documents in each subcorpus for the first two principal components, which together explain about 60% of the total variance.

In both plots, the translations from the European and the South Asian languages form distinguishable clusters, although the internal cohesion of these corpora appears more pronounced for the cosmopolitanism variables than for the literariness variables. The plots of the Anglophone postcolonial bestsellers, however, indicate a possible tension between these two categories. The postcolonial bestsellers are widely dispersed for the cosmopolitanism variables but exhibit a tendency to align with the South Asian translations. On the literariness variables, on the other hand, they appear more closely aligned with the European texts. Can we make the case that the postcolonial authors are more like the European authors with regard to the “literary” qualities of their texts but more similar to South Asian translated authors in terms of cosmopolitanism? This would constitute a significant challenge to conventional wisdom.

Table 3 and Table 5 provide an overview of the results for our measures of literariness and cosmopolitanism, respectively. To reiterate: to determine aggregate intra-textual variance we first calculate the sample variance of the Euclidean distance of each 500-word subsample of a document from the centroid of the document. The scores in these tables indicate the average of those sample variances for the entire corpus. The scores for the word-embedding-based variables indicate the average for the corpus of the cosine similarity of the individual document vectors to the keyword vector. Higher numbers indicate a greater similarity. Table 4 and Table 6 indicate the results of significance testing. Because the data has a normal distribution for some of the variables and non-normal distribution for others, we conducted both a t-test and a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for each variable. The p-values indicate whether the difference between two means for a given variable can be considered significant (i.e. to reflect a non-random difference in the population), and the effect sizes indicate the magnitude of the difference.

These more granular measures enrich our understanding of our results. First, both the English originals and the European translations register as more literary than the South Asian translations across all literariness variables except concreteness. Regarding the English-original (bestseller) corpus versus the South Asian corpus, this difference is statistically significant in the direction of greater literariness for five of the six variables (MSL, TTR, ITV, Concreteness, and Author). In the case of the European translations versus the South Asian translations, the corresponding number is also five of six (MSL, TTR, ITV, Literariness, and Author). By our measure, the takeaway is that both the English-original texts and the European translations register as more literary than the South Asian translations. Given the wide dispersal of the individual documents in each corpus—there is significant overlap in the PCA plots, and a given individual work may be in close proximity to either one or both of its comparison corpora—we should be cautious about drawing overly-ambitious conclusions.[17]

The effect sizes are also significant, helping confirm the similarity of European translations to the English-language originals. Where there are statistically significant differences between the European translations and the English originals, the effect sizes are all small. We should also note that the concreteness score offers little information that would help us disentangle these three corpora, since the European and the South Asian translations have approximately the same values. Finally, it strikes us as a bit puzzling that the word embeddings for “literary” do not provide a basis for definitively differentiating the corpora but those for “author” do. Future research will want to investigate the question of self-referentiality as a feature of the literariness of postcolonial literature, including the question of how to best measure it. Nonetheless, our preliminary investigation does indicate a similarity between this literature and translations from high-prestige European languages, one that is not duplicated in the South Asian translations. These results provide some evidence to support the claim that, in aggregate, the English-original texts are literary in a way that approximates the conventions of high prestige Western European literature.

Our results for the cosmopolitanism variables, on the other hand, points us towards an unexpected finding. All of the SDI measures, which indicate the diversity of geolocations with regard to major cities and geographic regions, are significantly higher for the English-original texts than they are for the South Asian texts.[18] In comparison with the European translations, there are no significant differences. In contrast to the literary measures, however, this alignment between the two subcorpora complicates existing claims regarding postcolonial literature. Whereas scholars have tended to see the literariness of postcolonial bestsellers as something that aligns them with other Western literary fiction, the cosmopolitan orientation has often been adduced as a feature unique to the postcolonial corpus. Our results, however, suggest that cosmopolitanism understood in terms of an urban and international orientation is not a distinctive feature of the postcolonial works. Rather, it is distinctive vis-à-vis a broad subcorpus of translations from South Asian languages, but not in comparison to European translations. Here the value of a corpus-based approach becomes apparent—rather than a distinguishing characteristic of works by these bestselling authors, these works, in their cosmopolitanism as well as in their literariness, would seem to mirror the conventions of their European counterparts. But this observation also requires a qualification. This assertion holds for our European translations when considered in the aggregate; however, if we subdivide the collection into French and German texts, we find substantial differences between them with regard to the “top cities” and the SDI variables. In other words, it may be the case that the dissimilarities in the geographical imaginary of global literature are driven by national traditions and are best addressed at this level.[19]

To say that the English-original works are not unique in this respect, however, is not to say that they are not unique at all. This brings us to what is perhaps the most revealing result of our analysis. A glance at Table 6 shows an almost perfect alignment between the English originals and the European translations regarding the cosmopolitanism variables. In all cases, both corpora exhibit a statistically significant difference from the South Asian translations in the direction of greater cosmopolitanism—with one exception. There is no statistically significant difference between the English-original texts and the South Asian translations in the case of the “family” vector (both also differ significantly from the European translations). In comparison with Western literary fiction, the uniqueness or the “exoticism” (to borrow a term from Huggan) of the of the postcolonial bestsellers appears to be as much a function of their focus on the family and extended kinship relations as of their interest in “interstitiality and transnationality.”[20] Midnight’s Children, to give one example, begins with a reflection on the narrator’s grandfather. And within in the first few pages of The God of Small Things, the narrator has already introduced the protagonist’s mother, father, brother, grandfather, grandmother, grandaunt, cousin, uncle, and step-aunt. Both of these novels begin with multi-generational familiar reminiscences that find parallels in such works from the corpus of South Asian translation as V.K. Madhavan Kutty’s The Unspoken Curse and (albeit in a different register) Qurratulain Hyder’s Fireflies in the Mist.[21]

The image of our postcolonial corpus that comes into view on the basis of the foregoing analysis, then, is one marked by similarities to European literature in terms of its literariness and its urban or global orientation, while being more like the South Asian translations corpus in terms of its preoccupation with familial relations. As we explained in the introduction, an important subset of recent scholarship on postcolonial literature has attempted to map its location in the Anglophone literary field and to understand how authors position themselves vis-á-vis the literary market. Often this research has undertaken careful textual and institutional analyses to determine how authors cope with the demands placed on them to serve as palatable spokespeople for their home regions, or how they attempt to short-circuit market-driven processes whereby expressions of dissent and resistance are transformed into easily digestible literary commodities. Our approach offers a new perspective on this positioning. The argument is less nuanced (and less normative), but it provides a valuable additional angle from which to consider the particular market niche that these works occupy, suggesting that they align with Western expectations for literary fiction in regard to their linguistic and semantic complexity and their international orientation, but that they are distinctive in their focus on kinship relations.

Two broader points are worth mentioning in this context. The first relates to what we refer to in the introduction as the differential pressures of the marketplace and the trade-offs that might be involved in reorienting the canon away from English-original works by bestselling postcolonial authors. These works do indeed seem to be more literary and cosmopolitan in their style and themes (relatively speaking), and thus can be seen to cater to Western tastes, albeit with a twist. It does appear to be the case that a shift towards translated works would provide readers with “a different picture of Indian writing than what is currently available today” (Ciocca and Srivastava 2). On the other hand, to turn toward the broader corpus of works translated into English from South Asian languages is to risk conveying an image of the region that reinforces its association with certain longstanding Eurocentric discourses and stereotypes surrounding the region’s modernization. This broad observation would need to be confirmed or refuted with regard to any particular work or subset of works under consideration. Nonetheless, this observation points to a potential area of concern that, to our knowledge, has received little to no attention in the scholarship. Additional scholarly work in this arena might help move the frequently ethically-charged assessments of this literature beyond a focus on the irresolvable dilemmas of postcolonial authorship (Brouillette) or the question of how their texts should be read (Huggan) to a more basic consideration of which texts to read and why. Regarding this final question, we hope that our analysis will also encourage additional investigations into the unique status of translations in a field that has formulated many of its claims on the basis of a group of “representative” authors who write in English.[22]

This brings us to the second point, which is that any claims about the unique characteristics of postcolonial bestsellers or translations must always be read against the backdrop of an implied comparison corpus or set of comparison corpora. The easily overlooked significance of this seemingly self-evident assertion comes into sharp relief in a corpus-based approach of the kind presented here. Can postcolonial authors be said to cater to Western tastes? The answer would seem to be yes, but it depends on which variables are being used to conduct the evaluation. Looking at a series of word embeddings, as we have seen, gives rise to a rather differentiated perspective on the question. And how generalizable is this claim? We noted significant differences (not shown in the reported data) between translations from French and German in terms of references to top cities and country SDI scores. In an earlier iteration of our analysis, we also considered translations from East Asian languages, but decided to limit ourselves to South Asia to ensure clarity of focus. It is not clear whether Chinese, or more significantly, non-translated texts from South Asian countries would align with the results we have presented here. Nor do we know how our postcolonial corpus would compare with other North American or British fiction originally written in English, nor with Latin American literature and works translated from Spanish. One of the contributions of our approach, as we suggested previously, is that we make these limitations explicit with clearly-defined control corpora rather than making pronouncements about a small collection of works without reflecting on its relative position within a global literary field. Such pronouncements can be both insightful and important, but they can also be enhanced by computational approaches. To give a specific example, Graham Huggan’s valuable observation that institutions such as the Booker have led “to the marketing of exotic writings to the Western world, rather than to the development of a body of postcolonial literature” (Postcolonial Exotic 412) can be productively extended if we consider that texts translated from South Asian languages may encourage a different kind of exoticizing appropriation, or that the exoticism of the “exotic writings” he mentions has as much to do with a focus on themes of kinship as with an interest in presenting a “a ‘counter-memory’ to the official historical confirmation” (“Prizing ‘otherness’” 419).

Limitations and Further Research

Many of the limitations of our analysis have already been addressed and are fairly self-evident. Most importantly, the variables we have chosen to measure are not beyond dispute, even though we are confident that they capture significant features of the corpora that are directly related to the hypotheses we are testing. Future research will want to develop new, and perhaps more sophisticated approaches to evaluating the literariness and the cosmopolitanism of works from the regions in question. In addition, there are several other allegedly distinctive features of postcolonial literature that we have not considered, for example, a preoccupation with politics (“a dismissive or parodic attitude towards the project of national culture” [Brennan 7]) or a celebration of hybrid identities. The arguments presented here could also be strengthened through close readings of a subset individual works, an addition that we were unable to include without dramatically extending the length of the paper.

In terms of the corpus, we have already mentioned the possibility of bringing in other regions for consideration. A less-obvious limitation has to do with the temporal distribution of the various subcorpora. Because a large number of the European translations were first published in the 1950s and 1960s, whereas virtually all of the English-language originals appeared after 1980, it is possible that broader shifts in literary culture might be influencing the results.[23] It might also be worth rerunning the analysis after removing all of the short-story collections from the corpus of translations. Although most of the texts in our corpra are novels, the two genres are subject to different conventions that may affect the variables under consideration, and thus a significantly higher proportion of one genre in one of the subcorpora could skew the results.

These limitations notwithstanding, we hope that the foregoing analysis opens up new perspectives from which to consider the distinctive features of postcolonial literature in a global context and provides a model for future multivariate and hypothesis-based analyses in computational literary studies.

Data Repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DDP4NB

Peer reviewers: Laura McGrath, Carmen Thong

Acknowledgements

The publication of this essay would not have been possible without the assistance of a number of colleagues. Andrew Piper and Stephen Pentecost played a crucial role in previous related publications, and Allie Blank conducted much of the initial analysis of the texts from Hathi Trust. We also received valuable feedback from participants in the summer fellows program in Digital Humanities at Washington University. Finally, we are grateful to the staff of the HTRC for their general support of the project as well as their help in navigating the capsule.

Such statements, however, would seem to be in tension with the fact that the novels analyzed in his study—Rushdie, Naipaul, Kureishi, Atwood, Roy, Zadie Smith, Coetzee, and Zulfikar Ghose—all write exclusively or primarily in English.

The framing of our research question was largely inspired by the work of Jey Sushil, whose dissertation investigates the features of works translated from Hindi into English.

As John Mee has written, “The appearance of Midnight’s Children (1981) brought about a renaissance in Indian writing in English which has outdone that of the 1930s” (127). On Rushdie’s impact, see also Sushil, esp. chapter 5.

20 of our 62 texts are written by women, as compared to 10 of the 62 texts included in the Goodreads list.

The Sahitya Akademi Award was established by India’s National Academy of Letters in 1954. It is awarded annually to writers of the most outstanding books published in one of India’s 24 major languages.

One author (Shashi Deshpande) is represented by five novels.

Detailed information on the compilation of this original collection, which consists of 10,631 translations of literary fiction into English from 120 different languages published since 1950, can be found in an earlier publication. (Erlin et al. 2022).

We identified the birth year of all authors and eliminated any titles written by authors born before 1900. While this method is imperfect, when combined with the publication dates from our Hathi source it provides reasonable assurance that the overwhelming majority of texts in the corpus were written after 1950.

These include Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Nepalese, Odia, Punjabi, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. There is also one text that is an adaptation of the Mahabharata and thus has Sanskrit listed as the original language.

Such effects have typically been discussed under the rubric of “translations universals” or “translationese,” although the question of how universal such effects actually are remains a matter of debate. See, for example, Volansky et al. 98-118. While it is also possible that our metrics might be impacted by structural features of the individual languages from which the translations are taken, e.g. Urdu versus Kannada, this possibility has little relevance for our analysis. After all, the claims being made about skewed representation assume the alternative to reading postcolonial bestsellers would be to read South Asian fiction in translation. In other words, practically speaking, any intervention into this particular debate must necessarily draw its conclusions on the basis of features present in the translated texts (rather than in the originals).

On the role of translation as a form of consecration, see Casanova 133-137.

For a cautious articulation of an argument about literariness and concreteness, see Cranenburgh et al: “It is tempting maybe to interpret these observations as indicating that literary language is associated with more formal and disinterested description, and that the preference for abstract notions suggests an intellectual horizon, while the propensity to use personal pronouns is more indicative for an interest in the ‘other’ than for the ‘self.’ This would then contrast to the rather more concrete notions of lesser literary texts that focus primarily on the self of the protagonist and her self-reflexive immediate social relations as she is immersed in hedonistic social events” (642). Additional support can be found in the work of Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, who have identified a general rise in concrete words in nineteenth-century British fiction. Within this context, however, their essay makes clear that genre fiction clearly has the highest frequency of such words. See Heuser and Le-Khac 32.

Such moments of literary self-reflexivity are often identified with the label “metafiction,” defined by Patricia Waugh as “a term given to fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality” (2). The spectrum of metafictional techniques far exceeds the scope of what can be established through word embeddings, but we believe that a preoccupation with literary themes is a reliable proxy for our purposes.

For all of these measures, it is important to remember that we are using 10,000-word samples from each text. This consistency in terms of length means that we do not need to scale our results. On the other hand, our sampling could lead to problems if references to geolocations are not distributed across the text in a roughly even fashion.

Our central inspiration here is Dipesh Chakrabarty, who specifically mentions Eric Hobsbawm’s characterization of the peasant insurgency in colonial India as “prepolitical” (11-13).

The role of the village and the family as key focal points of more archaic “communities” is crucial to Tönnies typology as well as Robert Redfield’s 1943 typology of a folk-urban continuum. For an overview of the role of “kinship” in the history of anthropology, including the idea that “so-called primitive societies, based as they are on ‘blood’ and kinship, are in some sense a distorted mirror image of our own (‘advanced’) society, based on ‘soil’ and the state,” (Peletz 343–72). See Michael G. Peletz, “Kinship Studies in Late Twentieth-Century Anthropology.” Regarding the body, Bikrum Singh Gill writes of how capitalism racializes “Indigenous and Black peoples […] as passive, irrational bodies, incapable of autonomously realizing the productive potential of that which is given by nature” (166). These are just a few scattered examples from a very large and interdisciplinary body of relevant scholarship.

Given the wide range of literary texts under consideration here as well as the type and scope of the variables considered, it would be a bit shocking if the clusters were more distinct.

It is worth noting that the effect size for “top cities” is small, indicating that the South Asian translations also focus on urban settings, even as they would seem to include fewer international locations. The data here is also rather sparse—a significant number of texts include no mentions of top cities. We have included these works in the calculation of our averages with a zero score.

For a related discussion of the distinctions between national literatures as regards their respective geographical imaginaries, see Erlin et al. 2021.

The word embeddings also suggest that the English-original texts are moderately more preoccupied with village life than the European translations, but substantially less so than is the case with the South Asian translations. The fact that the postcolonial texts occupy a midpoint between the other two corpora in this regard could be interpreted as evidence of a certain form of hybridity, but confirmation of this hypothesis would require additional analysis.

This kind of anecdotal evidence is by no means conclusive, but in combination with the quantitative results it provides additional meaningful support for our claims.

For more on the preoccupations of translations versus English-original works, see Sushil, chapter 4.

A preliminary analysis indicates that limiting the time frame to 1980 and later has a minimal impact on the average values for the variables we consider.