Introduction – Online Reviews and the Digital Condition

Digitization has significantly altered not only our perception of arts and literature, but also the way we talk about them. Multiple social reading platforms (e.g. LovelyBooks), blogs, social media services (e.g. Twitter) and sales platforms (e.g. Amazon) have become essential places for evaluating, reviewing and reflecting on cultural artefacts. The resulting data has become a promising base for research to answer some of the following questions: What are the peculiarities of review processes in the digital sphere? How do they differ among online platforms and across cultural domains, such as fine arts and literature? What influence do online platforms and their communities exert as socio-technical contexts for reviewing cultural artefacts? Eventually, these questions lead to the broader perspective of how online reviews and reviewing can be seen as a part of “the digital condition” as it was called by Felix Stalder (2018).[1]

We will begin by demonstrating why and how online reviews should not only be seen as texts, but as digital practices and – following Stalder – as part of “the digital condition” based on referentiality, communality and algorithmicity. Starting off with Stalders theoretical framework, we then proceed towards our hypothesis, which is that online reviews (of arts and books) are similar to what Stalder calls “communal formations”, that consist of shared knowledge and shared practices. To support this by empirical evidence, we will take into account selected results of the Rez@Kultur-project on online reviews that were collected between 2017 and 2020 at the University of Hildesheim.

Operationalizing “communal formations” to the level of textual forms, our main research question is whether and how online reviews from different platforms and cultural domains are different in terms of length and style. High similarities between reviews from the same platform in combination with a distinction between reviews from different platforms will indicate a platform-specific review pattern and point towards a “communal formation”, whereas high heterogeneity between reviews from the same platform might indicate a prevalence of individual styles and an absence of common denominators. Additionally, we will compare reviews of museums and literary works to crosscheck the alternative explanation that different review styles mainly originate from the different topics they cover and the corresponding cultural domain.

Our data were drawn from different literary review resources such as Amazon, BücherTreff.de, and various weblogs, but include also reviews of museums, exhibitions and general discussions of cultural objects, e.g. on Tripadvisor or independent weblogs.[2] Using methods from corpus linguistics,[3] we analyze the digital reviews in both datasets quantitatively: We examine whether there are differences between literary reviews and reviews of artworks or exhibitions that are observed as variation in lengths of reviews, sentence length, preferred use of parts of speech, syntactic patterns of sentences, and keywords. Taxonomies of different ‘digital social reading’ types, such as proposed by Stein (2010)[4], Ernst (2015)[5] and Kutzner et al (2019)[6], built the theoretical foundation for this research.[7]

Based on our results we draw the conclusion that, concerning style and length, reviews from different online platforms are much more distinct than reviews from different cultural domains (e.g. fine arts and literature). In other words, reviewers are influenced more by where they are writing than by what they write about. These findings support our hypothesis that online reviewing is based on platform-specific patterns and in this sense a form of a “communal formation”, formed by shared knowledge and shared practices. After detailing the study in the following sections, the limitations of our case study will be discussed in the last section of this paper.

Book and Museum Reviews as ‘Communal Formations’

Over the last few years, online reviews have become a subject of increased study.[8] Their impact on purchasing decisions has been examined,[9] as well as their value as user generated content.[10] Concerning literary reviews in particular, a focus has been put on stylistic and content aspects, describing online reviews as a form of amateur literary criticism.[11] Also in the case of literary reviews, research has started to use the growing amount of available data for empirical reception research[12] and methodological work.[13] So far, online reviews of literature and arts have been analyzed in different ways and from diverse perspectives, including praxeological ones. By applying a praxeological approach, we emphasize the conceptualization of online reviewing as a cultural practice, more precisely, we can examine whether ‘online review(s)’ can be seen as a generic term for various cultural practices in the sense that distinct formalizable types of reviews appear in distinct digital social contexts with presumably different social and cultural functions.

As early as 1996, von Heydebrand and Winko and proposed a theoretical framework for a praxeological perspective on literary evaluation, describing it as a “social action” (“soziales Handeln”) within the “social system of literature” (“Sozialsystem Literatur”).[14] Raphaela Knipp states “that media phenomena [such as online reviews] must be understood and investigated not only as textual or discursive constructs, but [as] embedded in action processes or specific, everyday ‘contexts of use’”.[15] Knipp demands a shift “from texts to practices” (“von den Texten zu den Praktiken”),[16] that would allow scholars of literary reception (and in our case more specifically reviewing) “to bring (everyday) action and everyday contexts […] into view.”[17] Important contributions to the concept of reading as a social practice have been made by Rehberg Sedo (2011).[18] Not only does she offer a theoretical approach towards “shared reading” as a “social process and a social formation” in her introduction,[19] the anthology itself gathers a wide range of different examples for these “reading communities” throughout history. In contrast to our own approach, Rehberg Sedo emphasizes interactional, personal and affective aspects of the “community”.[20] One important finding of various articles within the collection is that shared reading practices can lead to a ‘normalizing process’ concerning authority and rules within a group, especially over time and even in digital environments.[21] Our interest lies on similar kinds of ‘normalizing’ processes, but on a more formal and stylistic level and in a different context: the forms and patterns found in cultural reviews on asynchronous, potentially anonymous, and maybe only occasionally visited platforms and weblogs. Recent empirical research has already tried to comprehend and analyze reviewing processes on single platforms (e.g. Amazon) as practices, on a qualitative[22] as well as a quantitative level.[23]

Comparative research exists e.g. for English and Dutch corpora. Significant differences between the reviewers ‘behavior’ on Amazon and Goodreads were shown by Dimitrov et al. (2015),[24] indicating context sensitivity of reviews and different motivations of reviewers to post in different digital environments. Closer to our own research interest about review lengths and styles is the approach of Koolen, Boot and van Zundert (2020). Not only did they find normal distributions of review lengths on various Dutch platforms[25] (which is a hint –albeit a weak one– towards a normalizing social dynamic), but they could also confirm that “there are platform-specific factors playing a role in how much text reviewers write.”[26] However, their findings also suggest that the platform itself is not the only relevant factor at stake, but that the literary genre of the book[27] as well as individual characteristics of the reviewer (especially the frequency of their writing)[28] have an impact on the review’s form as well. But as we expect influences on review styles to be multifactorial, this does not contradict our hypothesis. In particular, as Rebora and Salgaro (2018) have already shown for an Italian review corpus, style can function as an important feature of distinguishing professional from journalistic and digital reviews,[29] and thus we suggest that styles are also distinguishable for digital reviewing practices of different platforms. However, so far, there is no comparative research for different reviewing platforms (including weblogs) and cultural domains in combination; and neither on German reviews. Filling this gap was the goal of the Rez@Kultur-project, from which this paper derives.[30]

To realize this, we use Felix Stalder’s concept of “the digital condition” as a theoretical framework from which we subsequently draw our hypothesis and analysis. In his book published in 2018, Stalder argues that with digitization we have stepped into a new paradigm of culture, that is characterized by three main forms: referentiality, communality and algorithmicity. In the way in which Stalder describes them, all three forms offer fruitful connections to understand reviewing processes as social and digital practices (see conclusion). Our main focus, though, will lie on the aspect of communality.

Inspired by Lave’s and Wenger’s concept of a community of practice[31] Stalder suggests to talk about “new communal formations”[32] as digital social spaces and epistemic communities that “arise in a field of practice” and “[are] characterized by informal but structured exchange, are focused on generating new knowledge and possibilities for action and are held together by the reflective interpretation of one’s own practice.”[33] Stalder names and describes different examples of these “communal formations” such as the free software movement, the Wikipedia community as well as certain social media platforms. He doesn’t get into detail about how the boundaries between different formations can be drawn. Especially in terms of social media this would be interesting, as different social groups might use the same platform differently and thus establish different practices and interpretative frames.

Those “interpretative frames” or “protocols” are established by doing, that is through the basic communicative actions within the communal formation. Protocols can be of technical nature (e.g. a certain programming language) as well as of a cultural one. The latter means that they structure “points of views, rules and action patterns on every level” and consequently “they ensure a certain cultural homogeneity, a set of similarities that give these formations their communal character in the first place.”[34] People within a “communal formation” follow these rules voluntarily,[35] i.e. not by the power of a sovereign, but – on the contrary – by the “power of sociability”.[36]

The question why these subjects take part in these kinds of formations, where their options of action and interpretation are limited by? the collectively established frames, is answered by Stalder in a general way only: “Communal formations” offer participants the opportunities to gain attention, recognition and feedback from their peers.[37] But more importantly they serve as tools for “selection, interpretation and constitutive agency”[38] within a space, where no comprehensive guiding culture exists anymore.[39] In this sense those “communal formations” become subjects themselves and transcend the individual.[40] The individual subjectivities that exist under “the digital condition” are not understood as “essentialist, but as performative”, they don’t need to provide a “coherent core”, but can present themselves differently in different “communal formations” and they (as well as their authenticity) are created temporarily.[41]

At first sight, the parallels between a “communal formation” and platforms as digital spaces where museums and literature are reviewed might not be striking. Traditionally we think of reviews as a certain text type that is used for a special reason[42], as von Heydebrand/Winko put it: evaluations (within reviews) appear to be shaped by “norms of the publication medium or individual axiological values of the reviewer”.[43] They are maybe also influenced by the artefact itself[44] and are generally written under the classical rhetoric premises that form follows function.[45] As above mentioned, there are good reasons to understand online reviews as cultural practices and even better reasons to conceptualize them as “communal formations”, because this perspective allows considering another determining factor for them: socio-technical dynamics in the digital world.

Against this background, we can now explicate that online review platforms and social reading platforms provide a set frame for the communicative actions of their users. Reviewing there, say on a platform like the German BücherTreff.de, is a shared practice based on shared knowledge and a shared “interpretative frame”, e.g. knowledge about the structure and different formats of the platforms (like reviews vs. comments) and a general interest in books. Writing a review is therefore a participation that produces difference (one’s own opinion about a certain book) and similarity at the same time (similar interest, text type and function). The reviewers are acting on a voluntary basis, they are, among other things, seeking recognition and feedback and their performed subjectivity is only constructed temporarily and partially through the review they publish.[46] But one central aspect of the concept of “communal formation” can’t be confirmed so easily: We hereby mean the aforementioned “cultural homogeneity” as a visible indicator of the functioning of communal “protocols”.

To examine whether reviews from a given platform can be seen as part of a “communal formation” that follow similar stylistic and formal rules, we analyzed data from three different reviewing platforms (BücherTreff.de, Amazon and Tripadvisor), and from various independent weblogs. All reviews were either written about books or museums. We decided to compare them by the following aspects: review length, sentence length, parts of speech, syntactic patterns of sentences and keywords. Finding high heterogeneity of those aspects within one platform would point to a prevalence of individual styles; finding high similarities between platforms and blogs from the same cultural domain would indicate a stronger influence of a broader social system (with its values, interpretative frames etc.; e.g. of the literary domain) than the concrete digital space of publishing, which in turn would suggest that communal formation-building has not taken place there yet. But as this is our hypothesis, we predict less similarities for the different digital spaces from the same cultural domain, but more homogeneity within one specific digital platform or format (like weblogs) and thus a visible tendency towards a “communal formation”.

Review Analysis with Methods of Corpus Linguistics

Corpora

Our corpus consists of online reviews written either about books or about museums. All texts were collected from multiple sources and can be divided into 5 subcorpora based on the type of source (digital platform) and the subject of the review (books or art).

For subcorpus 1 (Amazon) we used the publicly available Amazon Customer Review Dataset.[47] We used it to investigate the opinions of German book reviewers by separating the book reviews from all of the other product reviews and running a language detection program to find only the reviews written in German.

For the second book-centered subcorpus (BücherTreff.de) we gathered all forum entries for more than 39,000 books from the German reading forum BücherTreff.de published from 2003 till November 2018. Each forum entry was considered as an individual text. The third and fourth subcorpora contain reviews written in weblogs about books, as well as opinion pieces from weblogs about art and museums. The selection of the weblogs was performed after open field investigations that led to the systematization of different forms of reviews and platform features.[48] To cover a wide range of different blog-types, we chose weblogs that varied in a number of obvious characteristics, such as professionality (lay vs. professional reviewers), range of topics, gender, age etc. For each weblog subcorpus we chose 10 different blogs and crawled all the entries published as reviews. We decided not to further distinguish between each individual blog, but to combine all the reviews about books into one subcorpus and all the reviews about art into the other.

Additionally, we collected reviews about 10 German and Austrian museums and galleries from Tripadvisor.

Our data was collected and processed as part of the Rez@Kultur-project[49]. More details on the size of the subcorpora are given in Table 1.

Each subcorpus was annotated on various levels with linguistic and structural information such as lemmata, part-of-speech tags (with the help of RF-Tagger[50], with MULTEXT[51] using the STTS-Tagset[52]), syntactic information (the MATE Parser[53] was used to annotate dependencies). Additionally, reviews and comments to the reviews were annotated with titles, author names and timestamps, wherever this was possible. To allow for homogeneous querying, annotations were performed according to the IMS Open Corpus Workbench architecture[54].

Quantitative Tests

Collecting data from different sources (weblogs, a public forum and a reviewing platform) and not only according to a different subject (books vs. arts) gives us a unique opportunity for contrastive quantitative analysis of these digital spaces as well as for the interpretation of differences in subject matter. In order to maintain these distinctions we keep each subcorpus divided both by platform and cultural domain.

Our hypothesis is that different digital spaces from one cultural domain, for instance book or art reviews, exhibit less similarities, while specific digital platforms show a tendency towards a “communal formation”. With the aforementioned assumption in mind, we conducted the following quantitative tests (see below for motivation of features):

-

comparison of average review length for each subcorpus;

-

comparison of average sentence length for each subcorpus;

-

comparison of normalized distribution of parts-of-speech (only open classes: nouns, common and proper, adjectives, adverbs and verbs, main and auxiliary) for each subcorpus;

-

comparison of normalized distribution of subordinate clauses for each subcorpus;

-

comparison of keywords (most relevant words) and their distribution for each subcorpus;

In the following paragraphs we will explain our choice of these methods and their execution in detail.

The average text and sentence lengths is one of the most popular features. For instance, in stylometry (and register analysis) the length analysis can be used as discriminator of genre or register, which is why they are often used as a basis for comparison of the texts used in different corpora[55]. To check the statistical significance of the differences in review and sentence lengths across different platforms we performed the statistical hypothesis test ANOVA[56] implemented in python.

Information about parts-of-speech (distribution, ratio of open class parts of speech vs. closed classes, etc.) as part of the lexico-grammatical quantitative analysis is another widely used contrastive feature in corpus linguistics[57] The differences or similarities of the distribution of the preferred parts of speech for given platforms can signify “communal formation” or a lack of it at a lexical level, as well as indicate general communicative functions and patterns that can also be perceived as a part of communal formation.

We performed an analysis of the distributions of different open class parts of speech in each subcorpus. As the texts in our corpus stem from different text genres (customer reviews, forums, blog posts) which often determine length, we converted the raw counts (number of occurrences of specific linguistic features) into normalized values.[58] The same method was used for the investigation of subordinate clauses.

The analysis of grammatical structures such as the distribution of particular sentence patterns and clauses has been primarily of interest to psycholinguistic researchers as part of the studies on language acquisition and text production.[59] For example, Douglas et al.[60] provide a broad set of structural patterns and their frequencies found in a variety of written and spoken English corpora. Even more recently, Chik, S., & Taboada[61] examined the rhetorical patterns in online book reviews for English, Japanese and Chinese to perform contrastive analysis and to investigate cross-cultural variance. Their results showed that though all three languages shared a common structure of reviews, recommendation was absent in most of the Japanese reviews. For this paper we focused on the differences in the usage of various types of subordinate clauses: relative clauses, infinitive clauses and that- as well as wh-clauses.

The examination of terms or keywords that occur in a certain text corpus is another method of comparing lexical properties of different subcorpora. For our analysis we understand keywords as words and phrases that are characteristic of a particular text, words that occur with “unusual frequency in a given text”. In this case, “unusual” means high “by comparison with a reference corpus of some kind”.[62] The keywords and key phrases in our case were identified according to the methods typically used in the extraction of (e.g. technical) terminology from specialized corpora, as implemented, for example, by Schäfer.[63] First, a set of predefined syntactic patterns (formulated here in the style of CQP, the corpus Query Language used in our tools[64]) was used as search criteria for keyword-candidates: for instance, a query

[pos=“R-.*”][pos=“A-.*”][pos=“A-.*”][pos=“Nc.*”],

where [pos=“R-.*”] stands for any adverb, [pos=“A-.*”] for any adjective and [pos=“Nc.*”] for any common noun, would find all nominal phrases that consist of an adverb followed by two adjectives and a common noun, for example „sehr schöne […] gebundene Gesamt-Ausgabe [sic]"[65] (“very nice/nicely bound hardcover complete edition”). Then, the frequencies of each candidate found in the primary corpus were compared to the frequencies of the same words and phrases found in a reference corpus.[66] Finally, if certain phrases were found more often in the analyzed dataset than in the reference corpus, they are considered to be keywords.

The key phrases were investigated both quantitatively, when the normalized distributions were taken into account, and qualitatively, when we looked into the context and use of particular unique keyword phrases individually for each subcorpus.

Overall, we assume that the of the use of a quantitative approach applying statistical methods allows gaining a better understanding of the main formal, lexical and syntactic trends in our subcorpora. This in turn have ‘functional’ correlates in ‘doing reviewing’ and thus help identify differences and tendencies for further qualitative research, testing our hypothesis.

Quantitative Differences in Reviews

Review Length Analysis

For the analysis of review length and sentence length (next paragraph) we did not include information about comments and only looked into the reviews themselves. The bar graph (Figure 1) shows the average review length measured in words for each of the five subcorpora. The results show that reviews that originated from weblogs (about books and arts alike), tend to be much longer. The calculated p-value of the differences between review lengths for book blogs (average review length: 1.173) and for art blogs (average review length: 1.243) equaled 0.000, which indicates the aforementioned difference as statistically significant. We can thus conclude that already at the review-length level there is a statistical difference between blogs of different cultural domains. We also observed a significant difference when comparing the lengths of about 6,000 randomly chosen reviews from Amazon (average review length for the whole subcorpus: 155), BücherTreff.de (average review length for the whole subcorpus: 214), and Tripadvisor (average review length for the whole subcorpus: 65). According to the ANOVA significance test the p-value were also 0.000. This latter outcome supports our hypothesis that different platforms encourage different writing styles from their users – even if at the same time it also suggests a distinction between reviews about different cultural objects (books vs. arts).

Sentence Length Analysis

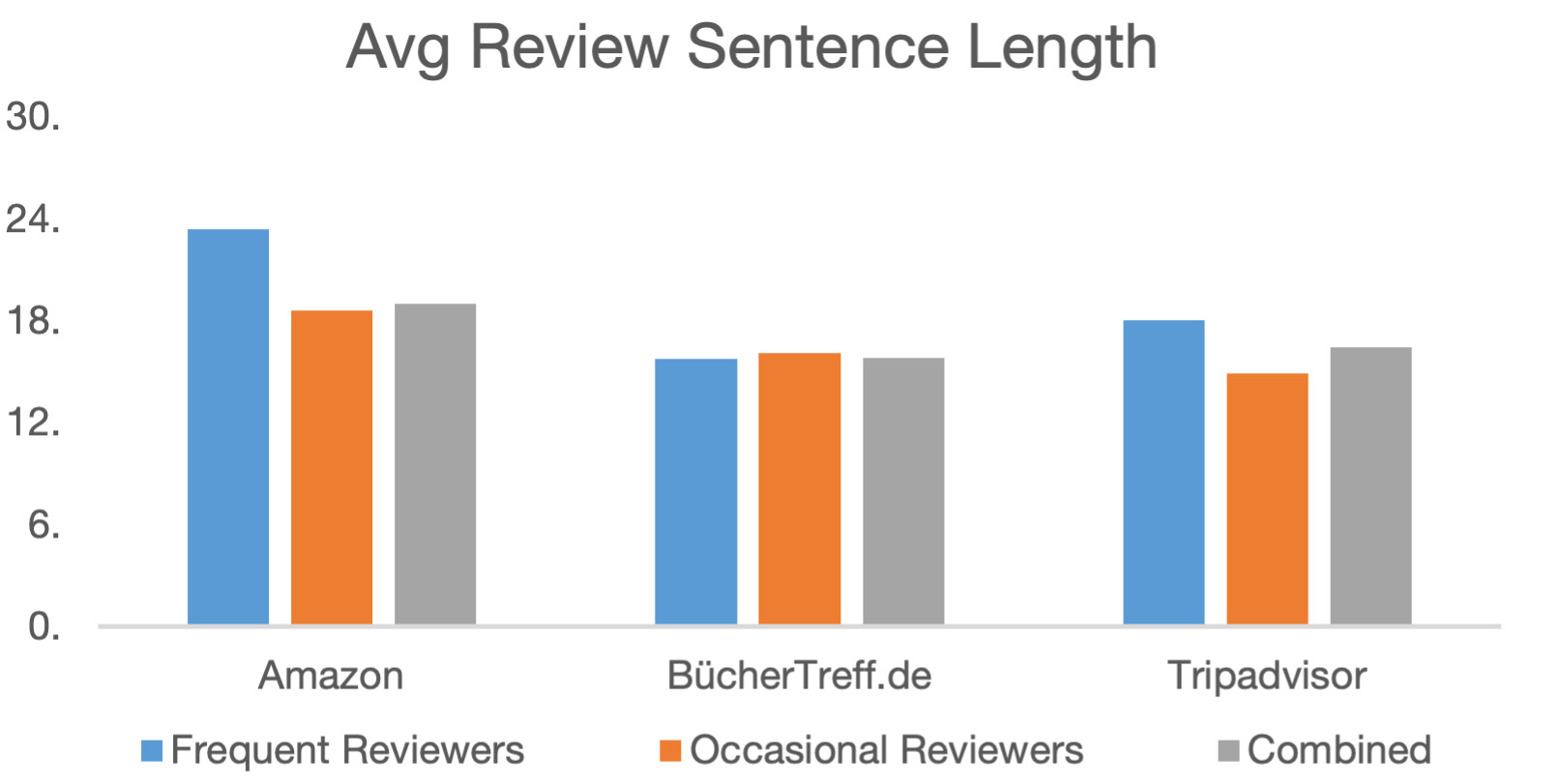

For the analysis of the average sentence length in reviews we first compared the review sentence lengths for the two types of weblogs (see Figure 2) with each other. On average a sentence in a review on a book blog consists of approximately 15.9 words. A sentence in a review from an art blog is typically made up of 15.8 words. The ANOVA test showed a p-value of 0.07, indicating that there is no significant difference in sentence length between blogs of different cultural domains.

The ANOVA test for comparing the subsets of sentences from the three larger reviewing platforms – Amazon (average sentence length: 18.98 words per sentence), BücherTreff.de (average sentence length: 15.78 words per sentence) and Tripadvisor (average sentence length: 16.42 words per sentence) – showed that the differences in sentence lengths were significant (the reported p-values below 0.002), with on average the longest sentences being produced at Amazon and the shortest ones on Büchertreff.de. The last figure may be explained by the forum-nature of the platform, where it is customary to greet newcomers to a discussion or to introduce oneself or to end a review with a complimentary close. In combination with the aforementioned non-significant difference in sentence length between weblogs about books and about art, these findings again support our hypothesis that reviews from different platforms are more distinct than reviews about different topics.

For the three platforms Amazon, BücherTreff.de, Tripadvisor, where multiple reviewers are encouraged to share their opinions, we decided to investigate in detail the writing behavior of frequent reviewers vs. occasional reviewers. We considered a reviewer with more than 3 reviews to be a frequent user of a given platform. Figure 3 depicts these different “types” by average sentence length. Blue bars represent frequent reviewers, orange bars illustrate occasional and gray bars are for all the reviewers without distinction. Average review lengths suggest that on Amazon and Tripadvisor the frequent reviewers tend to write longer sentences, while the reviewers on BücherTreff.de do not have this tendency. Nevertheless, the statistical analysis with ANOVA showed that the difference between occasional reviewers and frequent ones on both Amazon and BücherTreff.de is not significant: the p-value lies at 0.052 for Amazon and at 0.671 for BücherTreff.de. The results of the ANOVA test for Tripadvisor showed a significant difference in sentence length for occasional and frequent reviewers (p-value of 0.001). The discrepancies in the statistical analysis and the averages may be explained by the number of occasional vs. frequent reviewers for the given platforms. For Amazon only 9 % of all the review texts were written by frequent users. For Tripadvisor the amount of texts produced by frequent users was 0.05 % and for Büchertreff.de 92 %.

Regarding the standard deviations within each group, we could see that there are two different patterns for the distribution of the sentence lengths between frequent reviewers and occasional reviewers: one that is mediated by the platform itself and one that is influenced by the frequency of reviewing. On Tripadvisor we found bigger differences of sentence lengths within the group of frequent reviewers than we found within the group of occasional ones (SDfreq [7.14] > SDoccas [5.7]). This indicates that there is a top group of individuals, who write very often and very distinct while the vast majority uses the platform only occasionally to describe mainly highlights of their experience in a short form following the suggestions of the website. This may imply a platform-driven communal formation: seeing how others write about an exhibition or a trip to a museum and following the same route. On BücherTreff.de and on Amazon it is the other way around: There seems to be a slight assimilation effect to a common style, for those reviewers who often write reviews, as in both cases the standard deviations of frequent reviewers were lower than those of occasional ones (BücherTreff.de: SDfreq [6.28] < SDoccas [7.04]; Amazon: SDfreq [7.53] < SDoccas [7.81]). In these cases, we therefore suspect a community-driven effect, corresponding to the dynamics described in Stalders concept of a “communal formation”. Some extra support can be drawn from the BücherTreff.de data, as the effect is here stronger with most reviewers being frequent users of the platform.

Part-of-speech distribution

We continued our investigation of the differences between various review types by comparing the distribution of the open class parts of speech (PoS) such as nouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs. We differentiated between common and proper nouns as well as between auxiliary verbs (modal verbs included) and main verbs. Table 2 lists the distribution of different open class PoS in percent in relation to all of the parts of speech identified in the texts for each subcorpus. As it can be clearly seen from the table, art blogs use more common and proper nouns and adjectives than any other platform. This might be an indication of a slight tendency to use professional language. Book blogs (when compared to Art blogs), however, use more verbs (both main and auxiliary) and adverbs. When we compare platforms such as Amazon, BücherTreff.de and Tripadvisor, we again see nouns and adjectives used more frequently at Tripadvisor. Book discussion platforms on the other hand operate more with main verbs. Among all five subcorpora, Amazon users write reviews with the least nouns (both common or proper). We can summarize these tendencies as indicators for a stylistic continuum, where the most nominal (maybe technical) language of art blogs marks one end, and the most colloquial style on Amazon marks the opposite. Tripadvisor, BücherTreff.de as well as book blogs are situated in the middle area of this scale.

So far we can conclude that there are some part-of-speech preferences with regard to the subject of the review as well as to the platform used for reviewing, nevertheless the overall distribution of the abovementioned open class parts of speech (when considered as a whole) does not show any significant differences (p-value of 1.0 according to the ANOVA test). Some of the differences mentioned above may result from the mistakes from the automatic part-of-speech tagger, which operated at a fairly differentiated level of detection of lexical sub-categories.

Distribution of Subordinate Clauses

Next we take a closer look at the syntactic structure of the reviews and analyze the distribution of the different subordinate clauses in reviews. The use of more complex and sophisticated grammatical structures is often correlated with written style[67] and thus can be used as a contrastive marker to show which platforms tend to a spoken vs. a written style. In this case we distinguish between infinitive clauses (by counting instances of STTS markers „SubInf"), relative clauses (by counting instances of STTS markers „PRO.rel") and „that/wh"-clauses (by counting instances of STTS markers „SubFin"). The latter type covers sentences that include object clauses like: „Es dauerte lange, bis akzeptiert wurde, dass sich eine gut erfundene Geschichte mit Gewinn lesen lässt." (Translation: “It took a long time to accept that a well-imagined story could be read with profit.”). The percentage of each type of clause in relation to all sentences in a subcorpus is given in Figure 4.

The percentage of hypotactic sentences in blog reviews of different cultural domains is very similar, but slightly higher in book blogs. At BücherTreff.de and Amazon the numbers are very similar with two exceptions:

-

Relative sentences are less frequent on the two platforms than on blogs.

-

Amazon contains the highest amount of hypotactic sentences in proportion to the total amount of reviews (19.3 %).

-

Only 12 to 17 % of reviews in blogs contain hypotactic sentences. Correspondingly, the vast majority of reviews is written in paratactic style.

-

Reviews at Tripadvisor contain the least hypotactic sentences (in relation to the total amount of reviews [12%] as well as in relation to the total amount of sentences [18%]).

The p-value of the ANOVA test, when comparing the results for BücherTreff.de and Amazon, was 0.895, and thus indicated no significant difference in the distribution. When examining the distributions from both book reviewing platforms with the results obtained from the Tripadvisor dataset, the p-values was at 0.645 (not significant). The p-value when contrasting book and art blogs also showed no significant difference.

Overall, 32 % of all sentences found on Amazon had subordinate clauses, 30 % of all the sentences found within Büchertreff.de had subordinate clauses, Tripadvisor had only 18 %, while book blogs contained 33 % subordinate clauses and Art blogs – 29 %. Due to the lack of significance, these outcomes only weakly support our hypothesis: While we indeed see a higher similarity in data from the same cultural domain and higher differences in writing styles from different digital spaces of publication, we cannot statistically prove that this is more than just a coincidence.

Keywords

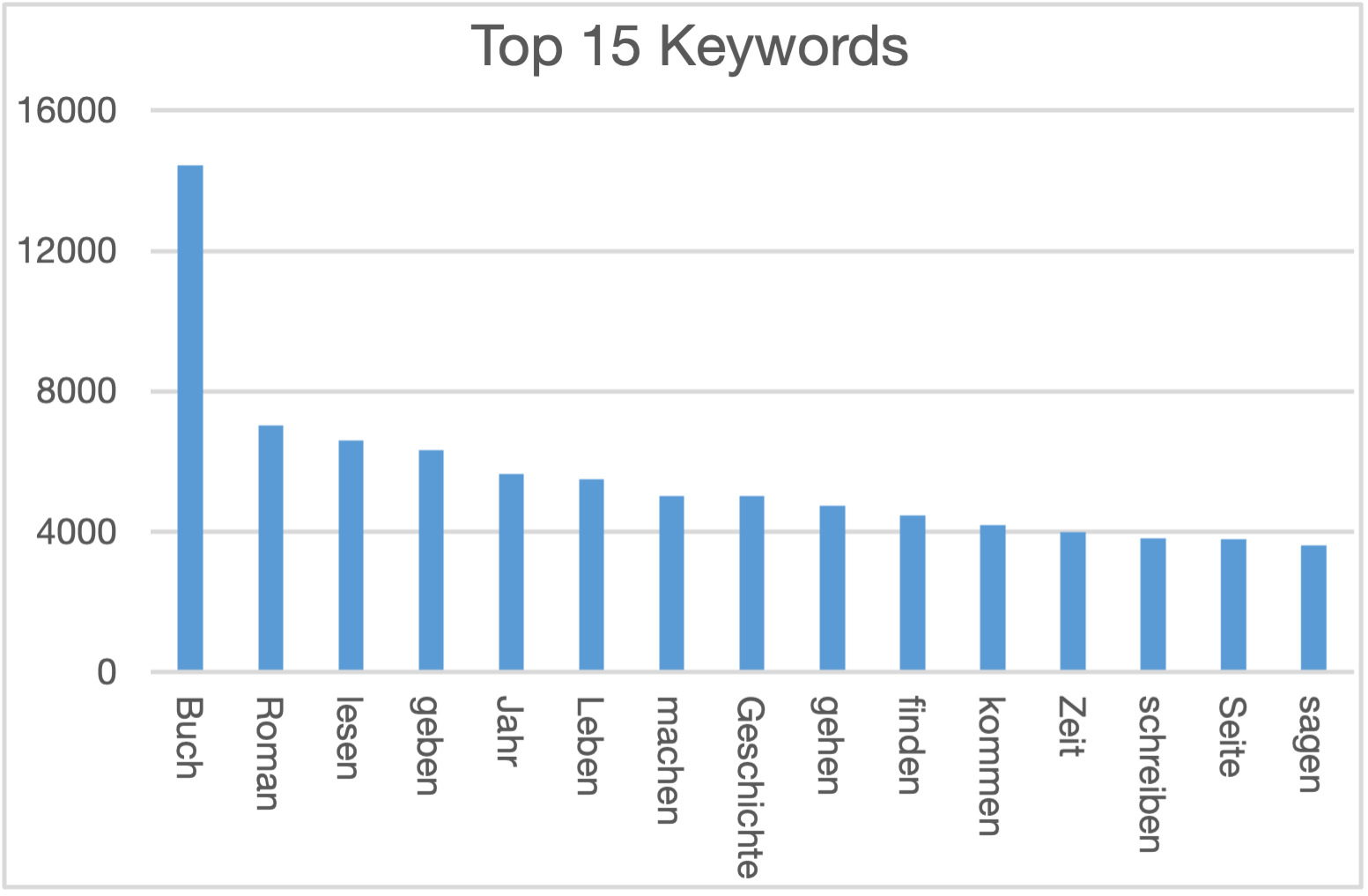

For this analysis we chose texts only from weblogs about books and Arts and used the large web-as-corpus data collection SdeWac[68] as a reference corpus. The keywords were extracted for both subcorpora (book blogs and art blogs) and for each weblog individually. Figures 5 and 6 list the 15 most frequent keywords (in German) found in art blogs and book blogs respectively. While all listed keywords are statistically significant the words that appear proportionally more often in the blog texts are depicted in the bottom of the figure.

A more precise look into the keyword lists showed that on average, reviews from different cultural domains contain common domain-specific keywords for example, for Art blogs: “exhibition” (“Ausstellung” with an absolute frequency of 3.304), “Art” (“Kunst”, 2.547), “museum” (“Museum”, 1.971), “drawing” (“Bild”, 1.827), and “Artist” (“Künstler”, 1.827). Among other frequent words we could also find some verbs: “show” (“zeigen”, 1.292), “see” (“sehen”, 1.284), “make” (“machen”, 1.187).

As with Art blogs, we also found domain-specific nouns among the most frequent keywords in book blogs: “book” (“Buch”, 14.432), “novel” (“Roman”, 7.022), “story” (“Geschichte”, 5.022), “page” (“Seite”, 3.784), and verbs: “read” (“lesen”, 6.597), “write” (“schreiben”, 3.822), “say” (“sagen”, 3.617). As the book blog subcorpus contains almost 3.5 times more tokens than the Art blog subcorpus, the identified keywords often have a higher absolute frequency.

To sum up, the reviews from different cultural domains contain common domain-specific keywords (on average), together with general verbs (geben, machen, gehen, finden / give, make, go, find) which we interpret to indicate non-professional’s language use within that domain.

Conclusion: On the Hybridity of Online Reviews

Overall, the various analyses show that online reviews from different platforms and formats (e.g. weblogs) differ in terms of sentence length and review length, concerning sentence structure and the distribution of parts of speech (see figure 7). This supports our hypothesis that each reviewing platform and format represents some kind of “communal formation” with its own practical and epistemic patterns and rules that are subtly enforced by collectively accepted protocols, including the technicall infrastructure.

On the other hand, online reviews from weblogs of different cultural domains did not differ much in text structure, length and interaction (between participants), but rather in their content (see keywords). According to that, the cultural domain as another possible independent variable on reviewing style does not seem as important as the actual digital space where the review is created, but it still has a huge influence on the topics that are covered. Again, this points to a platform-/format- or community-specific pattern more than to a distinctive way of talking about books or about museums. In other words, it is not so important what we write about, but where we write it, when it comes to the formation of a certain stylistic review pattern. Additional findings indicate the influence of each individual reviewing subject (in terms of thematic focus and experience).

The fact that individual decisions as well as the cultural domain still had effects on the reviews is not a contradiction to Stalder’s theory though. The results only show the complexity of the issue: As Stalder puts it, individuality and collectivity are created at the same time. We would like to add that collectivity is always multi-layered and that it, e.g. in this case, consists of the “communal formation” of reviewing at a certain online platform (with its technical constraints), but also of being part of a cultural/literary discourse. Those different levels of social/technical contexts can overlap and interfere with each other, and it seems to be a task for further research to figure out how they exactly interact in the case of online reviews.

Another factor that needs to be taken into account when we reflect the meanings of our results is the role of online platforms as governing institutions. As shown by Kutzner et al.,[69] online platforms for reviewing arts and books provide very different forms of support, of creative freedom, of incentives and guidelines. Accordingly, our results could also be understood as the successful implementation of the platforms’ strategies to lead their users into writing a specific kind of review. Motivations for this can be either economical ones (as probably in the case of Amazon and Tripadvisor), but also reasons of usability, or even of education. Even if we can only suggest this explanation and not test it with our current methods, we strongly support the idea that in the case of online reviews we are operating with a hybrid form of “communal formation”, that is established through a community as well as through the (technical) platform dispositive itself. In this hybridity we see a very typical feature of “the digital condition” that needs to be investigated in the future.

Stalder, Felix: Kultur der Digitalität. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2021 (2016).

The database will be described in detail in the method chapter later on.

For a detailed description of our methods, see the method chapter further down in this article.

Stein, Bob (2010). “A Taxonomy of Social Reading: A Proposal.” http://futureofthebook.org/social-reading/ (accessed 25th February 2022).

Ernst, Thomas. “User Generated Content” und der Leser-Autor als “Prosumer”. Potentiale und Probleme der Literaturkritik in Sozialen Medien". In Literaturkritik Heute, ed. Heinrich Kaulen, and Christina Gansel, 93–112, Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2015.

Kutzner, Kristin, Kristina Petzold, and Ralf Knackstedt. “Characterising Social Reading Platforms – A Taxonomy-Based Approach to Structure the Field.” In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, 676–690. 2019.

For empirical studies pointing into this very direction of stylistic differences between reviews from different platforms, see the section on previous research below.

See for a comprehensive and systematic overview Rebora, Simone, Peter Boot, Federico Pianzola, Brigitte Gasser, J. Berenike Herrmann, Maria Kraxenberger, Moniek M. Kuijpers, Gerhard Lauer, Piroska Lendvai, Thomas C. Messerli, Pasqualina Sorrentino (2021). “Digital humanities and digital social reading”. In Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Vol. 36, Supplement 2, Oxford University Press on behalf of EADH (2021), ii230–ii250.

Chevalier, Judith A., and Dina Mayzlin. “The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews.” Journal of marketing research, 43.3 (2006): 345–354. See also Kerstan, Wendy. Der Einfluss von Literaturkritik auf den Absatz von Publikumsbüchern. Marburg: LiteraturWissenschaft.de, 2006; and Sutton, Kim M. and Paulfeuerborn, Ina. “The influence of book blogs on the buying decisions of German readers.” Logos. Journal of the World Book Community, 28.1 (2017): 45–52.

See e.g. Bruns, Axel. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. New York: Peter Lang, 2008; Kirchmeier, Regina. „Bloggen und Kooperationen: Aus der Perspektive von Mikro-Influencern." In Influencer Relations. Marketing und PR mit digitalen Meinungsführern, ed. Annika Schach, and Timo Lommatzsch, 303–314. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2018.

See e.g. for German reviews Anz, Thomas. „Kontinuitäten und Veränderungen der Literaturkritik in Zeiten des Internets. Fünf Thesen und einige Bedenken." In Digitale Literaturvermittlung: Praxis, Forschung und Archivierung, ed. Renate Giacomuzzi, Stefan Neuhaus and Christiane Zintzen, 48–59. Innsbruck: Studien-Verl., 2010 (Angewandte Literaturwissenschaft, 10); Kellermann, Holger, and Gabriele Mehling. „Laienrezensionen auf amazon.de im Spannungsfeld zwischen Alltagskommunikation und professioneller Literaturkritik." In Die Rezension. Aktuelle Tendenzen der Literaturkritik, ed. Andrea Bartl, and Markus Behmer, 173–202. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2017 (Konnex, Volumne 22); Neuhaus, Stefan. „‚Leeres, auf Intellektualität zielendes Abrakadabra’. Veränderungen von Literaturkritik und Literaturrezeption im 21. Jahrhundert." In Literaturkritik heute. Tendenzen, Traditionen, Vermittlung, ed. Heinrich Kaulen, and Christina Gansel, 43–57. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2015. International research on the topic has been conducted e.g. by Allington, Daniel. “‘Power to the Reader’ or ‘Degradation of Literary Taste’? Professional critics and Amazon customers as reviewers of the inheritance of loss.” Language and Literature, 25.3 (2016): 254–78; McDonald, Ronan. The Death of the Critic. London, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007; and Johnson, Rebecca E. The New Gatekeepers: How Blogs Subverted Mainstream Book Reviews. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University, 2016.

See e.g. Driscoll, Beth, and DeNel Rehberg Sedo. “Faraway, so close: seeing the intimacy in Goodreads reviews”. Qualitative Inquiry (2018), 1–12; as well as the various publications by Lendvai, Kuijpers and Rebora on reading absorption e.g. Lendvai, Piroska, Simone Rebora, and Moniek M. Kuijpers (2019). “Identification of reading absorption in user-generated book reviews.” In Preliminary Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Natural Language Processing (KONVENS 2019). Erlangen: German Society for Computational Linguistics & Language Technology: 271–272. See also various articles in the anthology by Moser, Doris, and Claudia Dürr, eds. Über Bücher reden. Literaturrezeption in Lesegemeinschaften. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2021.

See e.g. Rebora, Simone, Piroska Lendvai, and Moniek M. Kuijpers. “Reader experience labeling automatized. Text similarity classification of user-generated book reviews.” In EADH2018 Book of Abstracts. Galway: National University of Ireland 2018.

von Heydebrand, Renate, and Simone Winko. Einführung in die Wertung von Literatur. Systematik – Geschichte – Legitimation. Paderborn: Schöningh, 1996 (UTB für Wissenschaft Uni-Taschenbücher, 1953), p. 78.

Knipp, Raphaela. „Literaturbezogene Praktiken. Überlegungen zu einer praxeologischen Rezeptionsforschung." Navigationen – Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften, 2017/17 (1): 95–116, here p. 95, translated by K. Petzold.

Ibid. p. 111, translated by K. Petzold.

Ibid. p. 112, translated by K. Petzold.

See Rehberg Sedo, DeNel, ed. Reading communities from salons to cyberspace. Basingstoke, New York. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Rehberg Sedo, DeNel. “An Introduction to Reading Communities: Processes and Formations”, in Reading communities from salons to cyberspace, ed. DeNel Rehberg Sedo, 1–24. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, here p. 1.

The common ground of the collected articles is, “that a community is comprised of relationships and that the people involved in these relationships feel they have an affiliation with one another”, ibid., p. 11.

Rehberg Sedo, DeNel. “‘I Used to Read Anything that Caught My Eye, But…’: Cultural Authority and Intermediaries in a Virtual Young Adult Book Club”. In Reading communities from salons to cyberspace, ed. DeNel Rehberg Sedo, 101–122. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, here p. 118.

See e.g. Stein, Stephan. „Laienliteraturkritik. Charakteristika und Funktionen von Laienrezensionen im Literaturbetrieb." In Literaturkritik heute. Tendenzen, Traditionen, Vermittlung, ed. Heinrich Kaulen, and Christina Gansel, 59–76. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2015.

See e.g. Bachmann-Stein, Andrea. „Zur Praxis des Bewertens in Laienrezensionen." In Literaturkritik heute. Tendenzen, Traditionen, Vermittlung, ed. Heinrich Kaulen and Christina Gansel, 77–91. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2015.

E.g. Dimitrov, Stefan, Faiyaz Al Zamal, Andrew Piper, and Derek Ruths. “Goodreads versus Amazon: The Effect of Decoupling Book Reviewing and Book Selling.”, in Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (2015), 602–605.

Koolen, Marijn, Peter Boot, and Joris J. van Zundert. “Online Book Reviews and the Computational Modelling of Reading Impact.” In CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2020: 149–169, here p. 154.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 156. See also Boot, Peter, and Marijn Koolen. “Captivating, splendid or instructive? Assessing the impact of reading in online book reviews”. Scientific Study of Literature 10.1 (2020): 66–93.

Koolen, Boot, and van Zundert, “Online Book Reviews and the Computational Modelling of Reading Impact”, p. 154.

Salgaro, Massimo, and Simone Rebora. “Measuring the ‘Critical Distance’. A corpus-based analysis of Italian book reviews.” In AIUCD2018 - Book of Abstracts. Bari: AIUCD (2018): 161–3.

See the full report of the project in Graf, Guido, Ralf Knackstedt, and Kristina Petzold, eds. Rezensiv-Online-Rezensionen und Kulturelle Bildung. Bielefeld: transcript, 2021.

Lave, Jean and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Learning in Doing. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 71 and 98.

Stalder, Kultur der Digitalität, p. 136 et seqq.

Ibid., p. 142.

Ibid., p. 162.

Stalder discusses the ambivalence of this voluntariness, as it is potentially complemented by exclusion or discrimination on an informal level. See p. 156 et seqq.

Ibid., p. 160. Referring to the concepts of David Singh Grewal. See Singh Grewal, David. Network Power: The Social Dynamics of Globalization. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2008.

Stalder, Kultur der Digitalität, p. 139.

Ibid., p. 151.

Ibid., p. 93.

Ibid., p. 151.

Ibid., p. 143.

For example, scholarly or journalistic needs (see Chong, Phillipa K.. Inside the critics’ circle. Book reviewing in uncertain times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020, here pp. 4 and 5), as well as entertainment, education, discourse (see Anz, Thomas. „Theorien und Analysen zur Literaturkritik und zur Wertung." In Literaturkritik. Geschichte, Theorie, Praxis, ed. Thomas Anz and Rainer Baasner, 194–219. München: Beck, 2004, here, p. 195 et seqq). Others add the advertising function (e.g. Jaumann, Herbert. „Literaturkritik." In Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft. Band 3, P bis Z, ed. Jan-Dirk Müller, 463–486. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 2007 (2003), here p. 463) or emphasize the aesthetic and literary value of criticism itself (e.g. Curtius, Ernst Robert. „Goethe als Kritiker." In Id. Kritische Essays zur europäischen Literatur, 31–57. Bern: Francke, 1950, here p. 32 et seqq.).

von Heydebrand and Winko, Einführung in die Wertung von Literatur. Systematik - Geschichte – Legitimation, p. 100.

See Reinwand-Weiss, Vanessa-Isabelle, and Claudia Rosskopf. „Erkenntnisse aus bildungstheoretischer Sicht." In Rezensiv – Online-Rezensionen und Kulturelle Bildung, ed. Guido Graf, Ralf Knackstedt and Kristina Petzold, 79–109, Bielefeld: transcript, 2021.

See the third step of elocutio in the classical rhetoric. Müller, Wolfgang G. „Rhetorik." In Metzler Lexikon Literatur- und Kulturtheorie. Ansätze – Personen – Grundbegriffe, ed. Ansgar Nünning, 656–657, Stuttgart, Weimar: Metzler, 2013 (1998), here p. 256.

Recent research on different types of online reviewing practices has revealed several social needs, that are sought to be addressed by reviewers, such as exchange (see Lukoschek, Katharina. „‚Ich liebe den Austausch mit Euch!’ Austausch über und anhand von Literatur in Social-Reading-Communities und auf Bücherblogs." In Die Rezension. Aktuelle Tendenzen der Literaturkritik, ed. Andrea Bartl, and Markus Behmer, 225–252. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2017) or social performance, as Knipp showed at the example of LovelyBooks (see Knipp, Raphaela. „Gemeinsam lesen. Zur Kollektivität des Lesens in analogen und digitalen Kontexten (LovelyBooks)." In Lesen X.0, ed. Sebastian Böck, Julian Ingelmann, Kai Matuszkiewicz, and Friederike Schruhl, 171–190. Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2017). ‘Temporality’ here is understood in the sense of performativity and seen as a genuine characteristic of digital communication. See e.g. Rainie, Harrison, and Barry Wellman. Networked. The new social operating system. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2012.

See McAuley, Julian, and Jure Leskovec. “Hidden Factors and Hidden Topics: Understanding Rating Dimensions with Review Text”. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2013.

Kutzner, Petzold, and Knackstedt, “Characterising Social Reading Platforms – A Taxonomy-Based Approach to Structure the Field”.

See a list of the included weblogs and all the results of the Rez@Kultur-project in: Graf, Knackstedt, and Petzold, Rezensiv – Online-Rezensionen und Kulturelle Bildung. For a detailed description of the data sampling see p. 43 et seqq. For more information on the corpora, see p. 411 et seqq.

See Schmid, Helmut, and Florian Laws. “Estimation of conditional probabilities with decision trees and an application to fine-grained POS tagging.” In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Computational Linguistics (Coling 2008), 777–784, Manchester, UK, 2008.

See Armstrong, Susan. “Multilingual texts tools and corpora.” Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 2011.

See Schiller Anne, Simone Teufel, Christine Stöckert, and Christine Thielen. „Guidelines für das Tagging deutscher Textcorpora mit STTS". In Technischer Bericht. Institut für Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universität Stuttgart, 1995.

See Bernd Bohnet, Ryan McDonald, Gonçalo Simões, Daniel Andor, Emily Pitler, and Joshua Maynez. 2018. “Morphosyntactic Tagging with a Meta-BiLSTM Model over Context Sensitive Token Encodings”. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2642–2652, Melbourne, Australia. Association for Computational Linguistics.

See Evert, Stefan, and Andrew Hardie. “Twenty-first century Corpus Workbench: Updating a query architecture for the new millennium”, University of Birmingham 2011.

See e.g. Oakes, Michael P. “50. Corpus linguistics and stylometry.” In Volume 2: 1070–1090. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2009.

Howell, David C. “Statistical methods for psychology”, Cengage Learning, (2012), 2008: 201–214.

Vincze, Veronika. “Domain differences in the distribution of parts of speech and dependency relations in Hungarian.” Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 20.4 (2013): 314–338.

Biber, Douglas and James K. Jones. “61. Quantitative methods in corpus linguistics.” In Corpus Linguistics. An International Handbook. Volume 2, 1286–1304. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2009.

See e.g. Desmet, Timothy, Marc Brysbaert, and Constantijn De Baecke. “The correspondence between sentence production and corpus frequencies in modifier attachment.” The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Section A 55.3 (2002): 879–896; Reali, Florencia, and Marten H. Christiansen. “Processing of relative clauses is made easier by frequency of occurrence.” Journal of memory and language 57.1 (2007): 1-23.

Roland, Douglas, Frederic Dick, and Jeffrey L. Elman. “Frequency of basic English grammatical structures: A corpus analysis.” Journal of memory and language. 57.3 (2007): 348–379.

Chik, Sonya, and Maite Taboada. «Generic structure and rhetorical relations of online book reviews in English, Japanese and Chinese.» in Contrastive Pragmatics 1.2 (2020): 143-179.

Scott, Mike. “PC analysis of key words – and key key words.” System 25.2 (1997): 233–245.

Schäfer, Johannes, Rösiger, Ina, Ulrich Heid, and Dorna, Michael. „Evaluating noise reduction strategies for terminology extraction." In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Terminology and Artificial Intelligence (TIA 2015), Universidad de Granada, Granada, 2015.

Evert, Stefan. “The CQP query language tutorial.” IMS Stuttgart CWB version 2 (2005): b90.

Amazon review, s.v. Sehr schöne gebundene Gesamt-Ausgabe Accessed September 11, 2021, https://www.amazon.de/gp/customer-reviews/R2DIXPG97Z1H2O/ref=cm_cr_getr_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8&ASIN=1840220767

See section “keywords”.

Roland, Dick, and Elman, “Frequency of basic English grammatical structures: A corpus analysis”.

Baroni, Marco, Silvia Bernardini, Adriano Ferraresi, and Eros Zanchetta. „The WaCky wide web: a collection of very large linguistically processed web-crawled corpora." Language resources and evaluation 43.3 (2009): 209–226.

Kutzner, Petzold, and Knackstedt, “Characterising Social Reading Platforms – A Taxonomy-Based Approach to Structure the Field”.