“Find them and hang them all traitorous bastards fuck all tyrants” – posted on Parler, January 6, 2021

“Good show today! It is looking like the protesters were let in. Many were Antifa/BLM.” – posted on Parler, January 7, 2021

Introduction

On the morning of January 6th, 2021, as Congress began their session to certify the votes from the November 2020 election, Donald Trump gave a speech at the Ellipse in Washington, D.C. to thousands of people attending the “Save America” rally, urging the assembled crowd to “walk down Pennsylvania Avenue” to the Capitol in a bid to halt the certification process (AP News). Although the march and the subsequent violent incursion into the Capitol caught many observers by surprise, the march was not much of a surprise to organizers, since it had been part of their planning since late December 2020 (Broadwater). Insurrectionists, who were among the organizers, had also begun discussions on social media platforms as far back as November 2020 of a rally, protest, and possible violent action against the certification process (VanDyke; Davies). Parler was among the most prominent social media forums where these discussions took place (Munn).

In the run-up to the 2020 election, right-leaning platforms such as Parler experienced substantial growth. Parler quickly became an “echo platform” populated largely by Trump supporters and advocates of the #stopthesteal movement (Cinelli, De Francisci Morales, et al.; Munn; Matthews et al.). Beyond simply expressing anger and negotiating a narrative of how the election had been “stolen,” contributors to the “parleys” (conversations on Parler) veered toward developing ideas about how best to respond to the threat to the Trump presidency and, in their minds, democracy. The amplification of specific discussion topics on the platform led to a convergence over the course of our study period on an underlying narrative framework that in turn acted as a feedback mechanism, structuring and guiding future conversations (Peck).[1] The discussions were not about whether the election had been stolen but rather how to beat back this profound threat and restore Trump to office (Zannettou et al.).

Although the conversations on Parler might simply have been “venting” (Rösner and Krämer), the subsequent violent actions of insurrectionists and their clear engagement with the platform suggest that their discussions carried with them the emerging formulation of a threat narrative that supported subsequent real-world actions (Munn). In threat narratives, an inside group perceives itself as confronted with a threat (or series of threats), often existential in scale, requiring a strategy for fighting back (Chavez; Loveland and Popescu; Wolfendale; Ciovacco). Stories such as anecdotes and personal experience stories, as well as partial stories, observations and commentary on those stories offer an opportunity to explore a range of strategies for dealing with a particular threat and, as the stories circulate across social networks of close, ideologically homogeneous groups, a consensus forms concerning the appropriate strategy—and a hoped-for outcome—for dealing with these threats (Tangherlini, “Who Ya Gonna Call?”; Tangherlini, “Toward a Generative Model”; Swidler). Computationally, the discussions can be modeled as a narrative framework graph, consisting of actants (nodes) and their relationships (edges). During storytelling, network paths are activated, new actants added, relationships emphasized, sides ascribed or inferred, and threats, strategies and possible outcomes solidified (Holur, Wang, et al.; Holur, Chong, et al.). Consequently, the underlying narrative framework encodes the cultural ideology of the group engaged in this process, guiding belief and, in some cases, real world action. In our following study of Parler, we develop a computational pipeline incorporating natural language processing, large language models and network analysis to uncover this underlying narrative framework (Bearman and Stovel; Sadler, “Narrative and Interpretation”; Tangherlini, Shahsavari, et al.; Sadler, Fragmented Narrative). This approach allows us to identify the discursive contours of an emergent conspiracy to counteract the perceived threats of the underlying conspiracy theory that motivates many posts to the site.

Prior Work

The January 6th insurrection has been the subject of far-ranging academic and journalistic investigations (Bakshy et al.).[2] These studies align with considerable research on the emergence of extreme political viewpoints on social media (Tucker et al.; Aldera et al.; Rajendran et al.; Torregrosa et al.), the rise of echo-chambers (Cinelli, De Francisci Morales, et al.; McKernan et al.)), the emergence of echo-platforms (Cinelli, Etta, et al.), the concept of conspiracy theory bricolage for people attempting to make sense of complex events (Greve et al.), and polarization, particularly in the political sphere (Adamic and Glance). Although Parler was a relative late comer to the realm of highly politicized social media (Luceri et al.), other forums, including the “chans”, were major loci for the emergence of conspiracy theories such as QAnon. On these platforms, which advertised themselves as supporting the right to freedom of expression, general rules regarding social interaction were abandoned in favor of an “anything goes” mentality (Baele et al.; Tuters; Colley and Moore; Israeli and Tsur).

Understanding social media posts at internet scale, the discursive context in which they are embedded, and their aggregate content, as well as the underlying role that this aggregate content has in shaping future conversations, has drawn considerable attention (Page et al.; Ouyang and McKeown; Li and Bamman). Several of these studies point to the collaborative nature of story and narrative creation on social media (Kim and Monroy-Hernandez; Dawson and Mäkelä). Very large-scale work on Twitter has had considerable success at extracting n-grams related to specific narratives from that platform (Alshaabi et al.; Dodds et al.). Zhao et al. present an approach to narrative discovery that aligns well with ours, although in their example they focus on COVID-19 and the 2017 French presidential election (Zhao et al.). Similar work on identifying narrative fragments and aggregating them into narrative frameworks have confirmed the usefulness of this approach in the context of political speech (Jing and Ahn; Abello et al.). Several refinements proposed by Zhao et al. show considerable promise for reducing the noise in the narrative framework graphs and understanding how these frameworks change over time (Zhao et al.). Their application of change point detection as a means for tracking changes in the underlying narrative frameworks helps identify those moments where the discursive arena experiences a potential inflection point (Zhao et al.; He et al.). We implement a simpler method that relies on changes in the daily ranked list of aggregated “supernodes”, with change points aligning with significant external events.

In a more qualitative, ethnographically anchored study, Dalsheim and Starret explore the carnivalesque aspects of January 6th, situating their observations in the context of the conflicting and overlapping narratives of modernity, thus providing thick descriptive context for the insurrection (Dalsheim and Starrett; Geertz). They note that the driving narrative of the insurrectionists was one that aimed “to protect a White vision of America against what many protestors saw as their country being stolen from its rightful owners” (Dalsheim and Starrett 9). Interestingly, their ethnographic observations also highlight the strong undercurrent of Christian rhetoric that informed the rally, an orientation that also plays a considerable role in the Parler discussions and adds additional evidence of the rise of “Christian nationalism” in the United States (Rowley; Norgaard and Walbert; Whitehead and Perry). Our work helps fill in the backstory of many of these events while also providing support for the observation that the rally was part of a “story war,” with conflicting narratives vying for space in the discursive arena (Dalsheim and Starrett 10).

Data

Prior to going offline, much of Parler’s data was downloaded and a dump of this data was made publicly available (Greenberg; Aliapoulios et al., “A Large Open Dataset”). We downloaded ~183M posts but did not download the metadata from the ~3.25M user accounts (Aliapoulios et al., An Early Look). In our subsequent processing, we deleted all personal identifying information and geotags, as we were neither interested in individual posters nor their location.[3] We removed urls, emojis, other non-ascii characters, and images/videos from the post data; we replaced non-standard quotation marks with their ASCII variants and newlines with a singular whitespace to prevent downstream errors. We iteratively tuned the cleaning to remove excessive punctuation, junk characters, whitespaces, and other posts that were automatically generated by the platform, or that were repetitive; these latter posts were often generic exhortations. Finally, we deleted one-word posts as well as multiple copies of the same post, retaining a single example based on the post’s first appearance. Each post was identified by a unique index along with a date and timestamp, allowing for drilldown to the underlying posts, thereby allowing us to operationalize a macroscopic approach supporting many scales of analysis, from the microscale of close reading, through meso-scales of daily graph analysis or subgraph investigation, to the macroscale of the entire narrative graph (Tangherlini, “The Folklore Macroscope”). Finally, we only retained posts that allowed us to extract entities, which we labeled “usable posts.”

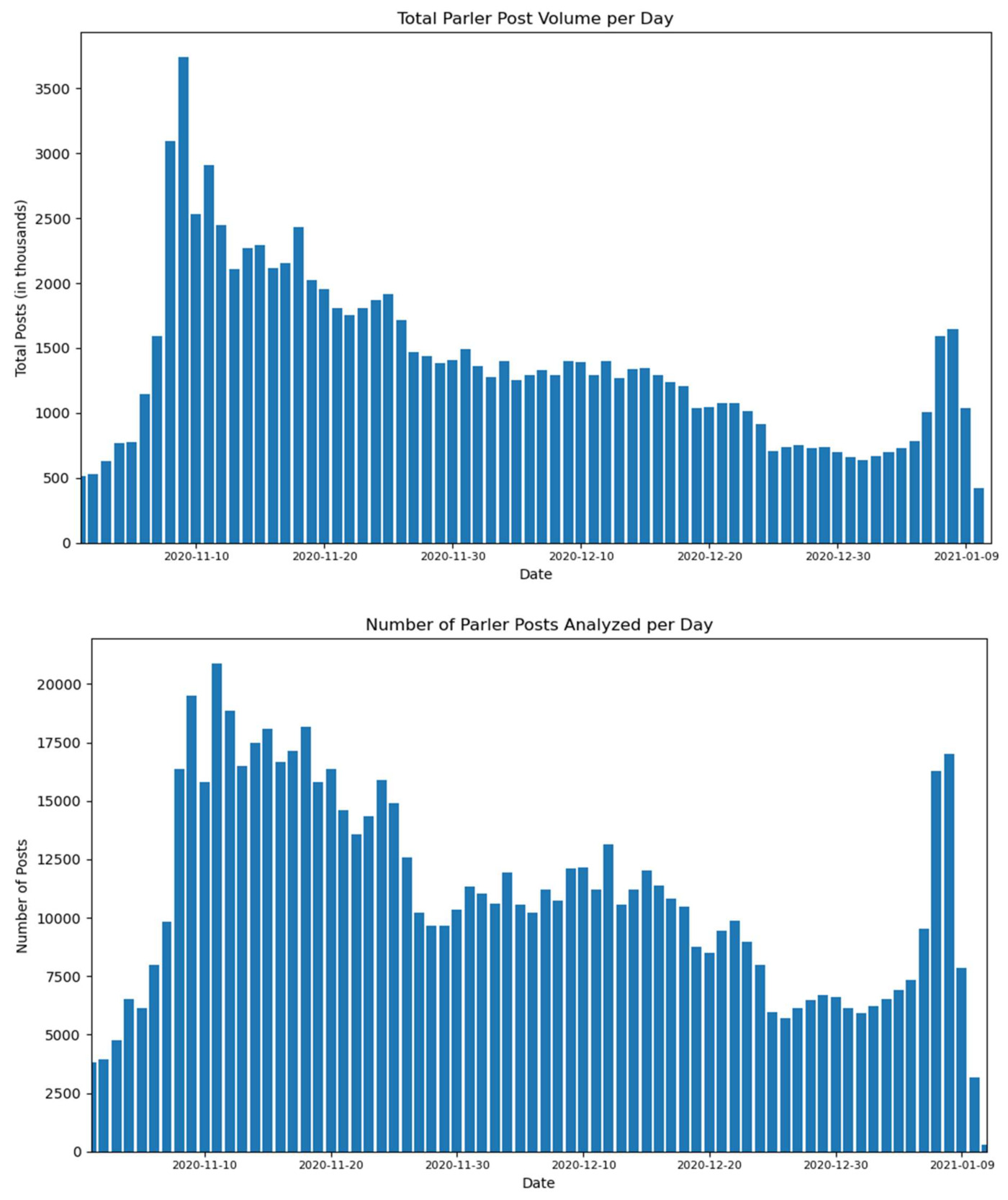

Because we were interested in the daily change of the narrative frameworks, we binned the posts by day. The number of posts per day on Parler varied greatly over the course of our study period, with the highest volume occurring on November 9, 2020 (3.74M posts) and the lowest volume occurring during the earliest days of November as well as the last day Parler was online (419k), with an average of ~1.295M posts per day (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, this volume was significantly greater than what our computing resources could handle.[4] Consequently, we randomly sampled 10% of usable posts in each daily bin, with 2,000 usable posts per day as a minimum threshold; we also added all the usable posts from January 11 to the final day’s graph. This process created 72 bins consisting of 783,021 posts, with an average of 10,876 posts per day (range of 3176 to 20,890).

Methods

For the methods deployed here, we modify earlier work on narrative extraction (Tangherlini, Roychowdhury, et al.) (Fig 2).

After cleaning, we push the data to the topic modeling module, here BERTopic (Grootendorst). BERT embeddings allow us to capture a semantic range that is often occluded in bag of words approaches. Although the standard cTFIDF topic labeling that BERTopic provides as a default is useful, we generate a second set of labels that applies Maximum Marginal Relevance, thereby maximizing the diversity of in-topic keywords. Because each of the posts is retained in the topic clusters, and because each post has a timestamp, we can calculate the change in the topic makeup over time. In our experiments, we found that including the global representation of the topics along with an evolutionary model aimed at discovering change allowed for a less spiky view of the shift in the focus of topic documents over time.

A second module focuses on discovering the underlying actant interaction space, where actants are identified through a combination of semantic role labeling (SRL) and named entity recognition (NER) (Tangherlini, Roychowdhury, et al.; Shahsavari et al.). The module also generates a ranked list of “supernodes” based on a concatenation of the context-specific appearances of actants so that references to “Mike Pence”, “Pence”, and “Penny”, for example, are all concatenated in the “Mike Pence” supernode, while context specific references are preserved as individual subnodes. Relationships between actants are encoded using verb phrases, while hyperedges are decomposed into a series of triples, so that a complex post such as, “Why are our leaders constantly blaming restaurants, bars and gyms as the biggest spreaders of COVID19 when the science says otherwise?”, can be decomposed into the following series of triples: {leaders} {blaming} {restaurants}, {leaders} {blaming} {bars}, {leaders} {blaming} {gyms}, {restaurants} {spread} {COVID19}, {bars}{spread} {COVID19}, {gyms} {spread} {COVID19}, {science} {says} {otherwise} (Tangherlini et al. “Mommy Blogs”). The resulting relationships (often verbs) are used as the edges in the graphs; when we construct the graphs, we add topic assignments as an edge feature. The final output of this module is a graph that encodes the subnodes and supernodes, as well as the edges describing interactant relationships, which can also be grouped according to the topic assignments discovered in the topic modeling step.

In the third module, we generate the narrative framework graphs and focus on two main aspects of the graphs: changes in the nodes and edges based on a binning of the graphs by date; and the identification of subgraphs that we label “narrative communities.” These sub-graphs describe one part of the much larger narrative framework and often consist of a particular sub-narrative, for example, the role of globalists in undermining election integrity.

We used the daily rankings of the supernodes (the concatenation of entities into a single entity) as a means for detecting change points in the overall narrative framework space. A change point was detected whenever the rankings of supernodes among the top fifteen for a particular day changed places by five or more positions. These changepoints were used to create bins for the subsequent aggregation of the narrative graphs, allowing a greater degree of granularity than if we had only worked with the entire graph. We also concatenated the daily graphs into a single union graph. Using the change point detection as a guide, we separated the daily graphs into bins and created additional versions of the graphs: a union graph and an intersection graph for each bin. The intersection graphs isolate those actants and relationships which are stable across the entire time frame of a bin. We also created a union graph of all the bins’ intersection graphs. During the analysis stage, various filters were applied to surface aspects of the graphs occluded by their density. We reduced density either by focusing on higher degree nodes or on certain topics; selecting topics related to “treason”, “fraud” and “Democrats,” for instance, reveals how these topics interact narratively within and across the narrative subgraphs.

Results and Discussion

The results of our multi-stage NLP and graph analytic approach provide a clear mapping of the range of discussions on Parler and reveal how these discussions rest on a single narrative framework. The broad contours of this narrative framework propose that the results of the election were fraudulent, with the deception orchestrated by globalists, Democrats and a vast conspiracy of fundamentally corrupt deep state actors and motivated by self-serving anti-Democratic impulses (the swamp), whose goals were to enrich themselves, undermine Christian values, erode the bulwarks of democracy and destroy a society built on law and order. As such, it is redolent of a comprehensive, totalizing conspiracy theory. A consensus developed that the best strategy to deal with this existential threat was to block the certification process “by any means necessary.” Thus, parallel to the thicket of posts that constructed, elaborated and confirmed the conspiracy theory of “Demonrats” working with globalists and the Chinese Communist Party to steal the election, were numerous posts planning a violent insurrection on Capitol Hill, using BLM/Antifa protests as a model, and using terms such as “peaceful protest” in a deliberately ironic manner.

In the following discussion, we reveal how certain sub-narrative frameworks are linked together to present a monologic world view where patriots and true Americans, characterized by their strong belief in a Christian God (signaled by various appeals to scripture), are threatened from multiple directions. We also show how certain narrative communities can, when considered in the broader narrative context, provide significant insight into how various signifiers, such as BLM or Antifa, are deployed within the discursive context as both justification for proposed actions and models for that action.

Supernode Rankings and Changepoints

The aggregate rankings of the super nodes provide a coarse yet informative view of the main actants in the Parler space. Not surprisingly, people including Trump, the Bidens (Joe and Hunter), Kamala Harris, and Mike Pence, all feature prominently, as do Stop the Steal advocates Scott Fitzgerald and Lin Wood, the globalist George Soros and the tech villain Bill Gates (Fig 3). God, Republicans, Democrats, China and the presidency round out the list of top actants. Further down the list, but still in high ranked positions, state actors such as Russia, and US states, including Georgia and Michigan, are joined by movements including the Proud Boys on the one hand, and BLM and Antifa on the other.

Although these entities are persistently present in the discussions, their relative importance shifts over time as new ideas are introduced into the conversations. Yet, the stability of the entities in the rankings lends support to the notion that the conversations on Parler were focused and consistent in their support of Trump from the start and the underlying consensus that the election was manipulated by multiple nefarious actors was a common point of departure.

We use changes in the rankings of super node actants to estimate change points in the conversation, which then inform the segmenting of the graphs into time-binned subgraphs (Table 1). In some cases, such as bin 8, the change point trails the event (Trump’s announcement of the January 6 rally), while in other cases the change point anticipates the event, such as bin 4 (the permit application and pardon of Flynn). The final bin is an exception, as the final planning, coordination and the events of January 6 all fall within this bin.

Topic Modeling

The topic modeling step provides an overview of the discussion space and, like the change points and entity rankings, is used to help further refine the narrative graph representations. To generate the topics, we pass the usable posts to BERTopic, and generate labels over the topics, thereby reducing the otherwise enormous relationship space that derives from the entity-relationship extractions.[5] Although the topic space is diverse, certain trends are immediately apparent on inspection, and make evident the strong right-wing, pro Trump, Christian chauvinist, “MAGA” slant of the conversations, with the main topics being the “swamp”, the Democrats (here most clearly associated with Biden), and the integrity of the presidential election (Table 2).[6]

These topics provide better insight into the contents of the conversations than the simple ranking of entities: there are community building comments that emphasize areas of agreement between posters; endorsements of QAnon positions captured by, among other things, references to WWG1WGA; discussions of broad social problems; and critiques of and accolades for various social media platforms and media outlets. The largest topic, labeled “swamp” along with Pence, Biden and Giuliani (here referred to as Rudy), captures a major theme in many of the discussions: the election outcome, with Biden as victor, was a result of the corrupt machinations of the Washington DC political swamp. Pence, charged with certifying the vote, and Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s point man on challenges to the outcome, would be the most important players in overturning the results. The second topic captures suspicions of the FBI and the broader role of deep state actors in manipulating the election, while other highly represented topics present conversations related to the connection between the Democrats and long-running enemies of the American right wing, such as the Socialists and Communists, who are often represented in these conversations by the Chinese Communist Party. These conversations align with broader discussions of treason as well as those focused on prominent Democrats and their possible alliances with un-American or un-Godly groups or activities. Potentially fraudulent state election counts, such as those in Georgia and Michigan, emerge in the topics that include many documents, and are supported by smaller, more focused topics relating to fraud, corruption, election machines and legal challenges to the counts. Interestingly, discussions of the COVID-19 pandemic and criticism of federal mandates related to masking and vaccination are clearly represented among these topics, including discussions of Fauci and his role as a metonymic stand-in for concerns about state overreach and scientific fraud. Not surprisingly, given the Christian nationalist slant of these discussions, Islam and Catholicism are both seen as religious threats (Bond and Neville-Shepard; Rowley).

While these topics, taken individually, offer a relatively fine-grained overview of the discussions, exploring their grouping based on their proximity in the topic space can provide clues about the relationships between various actants and discussions (Fig 4).

On a large branch of the dendrogram covering forty-five topics including the largest topic groupings, we discover a branch that has an aggregate label of “vaccine, dominion, swamp, pence, pelosi”, an unusually apt summary of the discussions on the platform. At a more granular level, we find specific inflections of these broader topic spaces. For example, there are accusations of treasonous behavior aimed at deep state actors and politicians, revelations that certain religious and political groups are involved in horrific practices such as pedophilia, that the COVID vaccinations and mask mandates were related to state overreach and faulty or fraudulent science, and that globalists and the tech industry pose an ongoing threat to Democracy.

A dynamic model that considers shifts in the topic space generated by daily posts provides additional insight into the variability in the discussion space over time (cf. Norton et al.). In a highly variable topic space, one would expect frequent changes in the top ranked topics, as well as considerable change in the top ranked words per topic. This is not the case for Parler, with a stable set of top-ranked topics and a similarly stable set of top ranked words (Fig 5 and Table 3).

Of note are the changes in the labels associated with the topics, as they indicate shifts in how the overall topic space is inflected at various points in time. For example, the main topic about “the swamp” shifts more toward discussions of individual senators and a fear of “Rino” insiders who may not support the overall attempts to reverse the election, before breaking on January 6 to mentions of treason, Pence and impeachment. Other similar shifts in the overall topic space can be traced through these dynamic shifts in the labels. The main goal of our use of the topic model is not, however, to provide an abstract summary of the Parler discussions, but rather to provide a mechanism for sorting the contexts in which various entities in the overall narrative graphs interact.

Narrative Framework Graphs

The main output of our pipeline is a series of graphs that capture the narrative framework. The comprehensive graph for the entire study period presents as a “hairball” (Fig 6). To disentangle it, we apply a modularity-based community detection algorithm coupled to a simple labeling step to provide overviews of the sub-narratives and their interconnections (Utriainen and Morris). In these clustered graphs, each edge is assigned a topic. We first consider the narrative frameworks in their entirety, including a discussion of the narrative space implied by smaller subgraphs that capture fundamentally stable aspects of the story space. We conclude with more focused discussions of the narrative graphs for the bins discovered by our simple change point method. For the sake of brevity, we do not consider all the graphs and subgraphs but rather focus on those that help illustrate the overall narrative space. The graphs show that people posting on the platform see their way of life threatened from numerous directions, recapitulating in their storytelling essentially all aspects of Barkun’s model of threat in conspiracy theory, where threat can come from the outside (foreign powers), from the inside (“Rinos” and other “treasonous” actors), from above (globalists and the super-rich), and from below (immigrants, BLM and Antifa) (Barkun). The graphs also reveal how the strategy for dealing with these threats leads to an organized effort—in essence, a conspiracy—for a violent protest on Capitol Hill that, in the words of one poster, will take the “Peaceful Protesting of our opposing side and just raise the bar, a few notches!” (November 17).

Comprehensive Graphs

A union graph of all the days in the study period provides a broad and informative overview of the narrative frameworks driving Parler conversations and their interconnections. Although this main graph presents as a nearly intractable hairball (V=26981, E=3220666, density=0.003, clustering coefficient = 0.61, 79 connected components, with one giant connected component accounting for 63% of vertices), the decomposition of the graph into subgraphs reveals some large, semantically coherent narrative communities (Fig 6). Most prominent among these clusters is a central conversation about Washington, corruption, Democrats, the deep state and the stolen election. Other prominent narrative clusters incorporate discussions of class warfare, China, antifa, the pandemic and vaccination.

These subgraphs can be further decomposed into additional subgraphs that in turn reveal an increasingly fine-grained view of the components as interlocking narrative communities. For instance, one of the larger narrative clusters in the union graph details the role of George Soros and other globalists with their connections to deep state actors such as the CIA and Obama holdovers and their alliance with Marxists and communists, thereby emphasizing their role as enemies of America and her patriotic defenders (Fig 7).

Binned graphs

The contours of the conspiracy theorizing narrative framework becomes clearer through consideration of the complete graphs for each bin and their attendant subgraphs. It is also in these subgraphs that one finds evidence of the emerging conspiracy to take violent action in Washington. The initial narrative groupings in the bin comprising conversations during the run up to the election (November 1-3) already reveal a strong pro-Trump slant to the discussions. Conspiracy theorizing about Hunter Biden, the deep state, Antifa and the connection between the Democrats and socialist/communist forces takes up a large part of the narrative space, with the intercommunity edges coming from a small number of topics (Fig 8). A clear illustration of a small set of topics linking two communities appears between the large subgraph labeled “communist, antifa, socialist” and the smaller “muslim, scum, tech” subgraph, where the edges come exclusively from topics labeled swamp (0), communist (1), Georgia (3), masks (13), antifa (17), and Omar/muslims (36). Concerns about voting are also apparent in graphs from bin 1, even though the election has yet to happen.

In the subsequent bins the narratives become more elaborate, yet the core remains largely the same (Fig 9). The main narrative community in these bins consistently focuses on deep state actors and their machinations to deny Trump’s election. Patriots, family and God are strongly arrayed against these forces, while secondary narrative clusters generate the broad conspiracy theories of globalists, Hunter Biden and his corruption, the role of the Chinese Communist party, and a strong socialist/anti-Americanism among Democrats.

A closeup of a narrative community further partitioned into smaller communities from bin 6, which begins with the Proud Boys March on Washington, ramps up the discussions of alternative slates of electors. The Capitol, which was the site of the Proud Boys march, emerges as a likely locus for future protest, while discussions about the role of globalists and foreign state actors in stealing the election reveals dense connections between these otherwise disparate discursive arenas (Fig 10).

Ivy league professors and other left wing actants are connected through edges with the topics “communists” (2) and “Pelosi” (4) to treasonous politicians in the “Hunter agenda soul Obama” cluster, while the Antichrist cluster is linked through “swamp” (0) and “Communist” (2) edges to Dominion and ballot stealing in the main Sydney Powell cluster. In contrast, the “Helping patriot police” cluster, with a prominent “Trump martial law” node is connected by edges in the “Barr” topic (22) to supportive nodes such as “Republicans” in the “democrat mass communist” cluster and Kyle Rittenhouse in the “socialist online harmful” cluster. This pattern of specific topic edges between subgraphs repeats itself across all our decompositions and lends support to the hypothesis that these narrative subgraphs are connected through edges, largely encoding verb phrases, that are dependent on ideologically motivated interpretations of events or other forms of speculation.

By the later bins, the narrative landscape is clear and consistent, with Democrats aligned with globalists, foreign and deep state actors, tech billionaires, and possibly Satan to undermine the election. Bin 7, covering the period from December 18 when Trump announces the January 6th rally to December 27th, the day prior to Jeffrey Clark sending a letter to Georgia alleging an ongoing investigation into election irregularities, for example, has a major narrative component focused on the Clintons who had previously figured prominently in Pizzagate, with its accusations of Satanic pedophilic cannibalism, and later QAnon; here, they are closely tied narratively to Hollywood, Iran, and Communists. In bin 8, the penultimate grouping covering the period from the Clark letter to the day prior to the Capitol police report warning of potential violence on January 6, one finds a large narrative component focused on prominent Republican party members and an increasing suspicion that they lack commitment to Trump, the broader patriot movement and, by extension, the country (Fig 11).

The graphs from the final bin stand as an outlier, as they include real-time posts from the insurrection as well as posts made in its immediate aftermath. In the days after the insurrection, the antagonistic BLM/Antifa narrative components are flipped on their head, with the violence at the Capitol being blamed in large part on infiltrators from these movements. In one Antifa focused cluster, the role of Antifa, possibly in collusion with the Capitol police and the “dems” overwhelm the patriots and supporters of Trump (Fig 12).

Hiding within the thicket of these conversations starting early in November is the emergent consensus that the best way to challenge the threat to the election posed by the all the different groups marshaled against God, country, patriots and Trump is to plan a protest that matches the perceived violence of Antifa-instigated actions during the BLM protest in the summer of 2020. Exhortations to violent, retributive action and commitments of organizational infrastructure are largely embedded in conversations about BLM and Antifa, and include calls for armed resistance, such as “resist this tyrant [Biden] with every fiber of your being,” while making clear Biden’s close connection to globalists, nazis, big tech, and Islam (Fig 13). Various posts offer aid in organizing, such as “Guys, ten million to Washington is focused on bringing patriot groups together nationwide. If you have a rally or patriot group that needs support…please send us the information…we will help raise awareness”, while posts in the narrative neighborhood of BLM/Antifa endorse violence as a central strategy: “The US Constitution allows for hostile inauguration of a president elect. Will you be first to pick up arms?”

Although there is no single narrative community that could be labeled “strategy” or “armed insurrection,” the conversations emerge across all the different narrative communities, occluded by the more elaborate conspiracy theorizing, yet with the immanent strategy of a violent recovery of the stolen election.

Intersection and Union Graphs

We create an additional set of graphs that capture the intersection of the otherwise dense graphs of actants and relationships for each day in the individual bins. By intersecting the graphs, we capture the consistent features of the narrative frameworks for each bin (Fig 14). Although the method is simple, it reveals shifts in the narrative space over time and, just as importantly, a remarkable consistency in main actants and their relationships, adding additional confirmatory evidence to the observation that the narrative frameworks on Parler were highly focused and consistent despite the enormous rise in users after the flight from mainstream platforms such as Twitter (now X) and Facebook.

For example, the intersection graph for bin 1 (Fig. 14a), in the lead up to the election, presents a relatively simple narrative, with the Trump White House aligned with God in a struggle against the deep state and Chinese Communist party; most of the edges come from topic 0, labeled “Pence, swamp, Biden, Rudy.” In bin 2, the conversations become more detailed, and a consistent message begins to emerge: God is on the side of the American people, who support Trump, while the Communist-influenced Democrats have been involved in perpetrating election fraud. Bins 3 and 4 continue to elaborate on this core narrative, with increasing ire directed at deep state actors such as the FBI, and the ongoing threats of leftists to God and family, with bin 4 emphasizing the role of the Chinese Communist Party in undermining the election. In bin 5, discussions of the pandemic become prominent along with holiday greetings. In bin 6, the alignment of Democrats with communists, socialists, abortionists and pedophiles is apparent, as the president is even more overtly aligned with God and family; edges related to Georgia and the efforts to force a recount are prominent as well, while Bill Gates and efforts at vaccination form a prominent, although disconnected, cluster. In bin 7, the intersection of the narrative graphs becomes less complex, with China and the Democrats aligned clearly against Trump and God, a condensed narrative echoed in bin 8 and the immediate run up to January 6. Importantly, in bin 9, which includes the aftermath of the insurrection, Mike Pence is closely connected to the Democrats, while America and God are closely connected in their own cluster, in opposition to the swamp and the deep state. The Chinese Communist Party continues to influence the Democrats, while Trump, Republicans and patriots play prominent roles in the main narrative cluster.

Conclusion

The events of January 6th are difficult to forget. There has been considerable ink spilled in understanding the confluence of various forces and ideologies that led to the violent insurrection. The discussions on Parler, which we model as driven by an underlying narrative framework, provide insight into some of these forces, and help chart the role that social media may have played in generating consensus both in the context of answering “what happened?,” but also providing support for emerging answers to the question, “what should we do about it?” In a series of narrative links breathtaking in scope, posters on Parler activated many of the different conspiracy theories that had been elaborated by Pizzagate and QAnon forums, and during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the abstract level of the narrative framework, the posters on Parler proposed that deep state actors such as the FBI, who constitute the “swamp” of Washington DC, used their positions of power to collude with state election officials, such as those in Georgia, to corrupt the election process, relying on suspect technology, such as Dominion’s voting machines and servers in foreign countries or satellites controlled by foreign state actors, as well as the machinations of corrupt local and state officials, to elect Joe Biden president. Globalists, tech titans and the mainstream media and popular social media platforms used their untold wealth and extraordinary reach to continue their increasing control of both the economy and power. Democrats, intent on destroying the fabric of God-fearing American culture, and buoyed by the anarchic Antifa and violently treasonous BLM, linked up with socialist and communist forces, most notably the Chinese Communist Party, to pose a sustained threat to American family values, perhaps best seen in their association with Jeffrey Epstein, Hollywood, trafficking and Satanic pedophilia. The COVID-19 pandemic was largely a hoax that, through the offices of the CDC and Fauci, allowed the state to force Americans to submit to restrictions to freedom of movement and threats to their bodily autonomy through vaccination.

These narrative threats to the integrity of the community of God-loving/fearing American patriots demanded action. By mid-November, a conspiracy to take real world action against these narratively constructed threats began forming. In these organizational threads, “patriot” groups offered each other support, while reaching agreement that the date of their action would be January 6th, offering Mike Pence an opportunity to show his true colors; indeed, considerable discussion surrounded the question of whether he would support the true Americans or whether he would reveal himself to be a traitor to the cause. The intentions for this protest were almost certainly violent from the very beginning, with discussions about the planned event linked to discussions of BLM demonstrations from the summer of 2020 that were uniformly seen by posters on the platform as violent, anti-democratic, “fascist” activities, instigated largely by anarchic Antifa protesters. Combining misinformed readings of American history and law with a posture of macho militarism through references to Michael Flynn, guns and ammo, the solution to the imagined threat was to “[k]ill the EVIL LEFTIST SCUM, before they kill you! Stand up KILL for your country, Americans! TAKE TO THE STREETS IN YOUR tens of MILLIONS! Start a REVOLUTION.” In short, posters on Parler were organizing a dangerous real-world conspiracy to counteract the threats of the conspiracy theory they had generated on that same platform.

Data Repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/B8FPFM

This phenomenon of a quickly emergent and stabilizing narrative framework that undergirds conversations on social media forums has also been observed in other contexts including vaccination hesitancy, the PizzaGate and QAnon conspiracy theories, COVID-19 conspiracy theorizing, and political discussions about highly polarized issues such as gun control and abortion (Tangherlini, Roychowdhury, et al.; Tangherlini, Shahsavari, et al.; Shahsavari et al.; Holur, Wang, et al.; Zhao et al.; Chong et al 2021).

An excellent journalistic overview of the January 6 insurrection can be found in the New York Times “Capitol Riot Investigations” collection and the Washington Post, “The Jan. 6 Insurrection” collection. The Report of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol provides considerable investigative insight into the broad events leading up to and the progression of the events of January 6 (2023). The anthology edited by Jeppesen et al. (2022) provides a series of essays that offer critical perspectives on multiple aspects of the insurrection, its supporters, and the diverse roles that social media played in the event.

We created a randomized, anonymized index of the accounts so that we could keep track of posts and reposts by individual accounts without any method for reattaching the user accounts to that index.

Extraction of the daily narrative graph with a minimum of 2,000 and average of 10,876 usable posts took ~120 minutes on the UC Berkeley Savio HPC cluster. Total cluster time was ~147 hours.

We limit the number of topics to 150 to prevent an overgeneration of fine-grained topics. Without a limitation on the number of topics, BERTopic finds 3,888 topics, when the smallest permissible cluster size is set to 15, and the Riemannian manifold for UMAP is set to 5 dimensions. Since the goal is not to generate a fine-grained topic model, but rather to classify edges to reduce graph density, we set a much smaller limit on the number of topics.

We do not include the unassigned documents here (Topic “-1” in BERTopic), even though documents assigned to that topic represent a significant and complex aspect of Parler discussions—although we could have forced a topic assignment for each extraction, such an approach would have done little to make the topic clusters more informative. Instead, we consider the unassigned edges in the broader narrative graph analysis below.