Introduction[1]

The German publication market is one of the most active in Europe when it comes to publishing translations. With 208,240 translated titles with German as the original language, according to the Index Translationum, German is the third most translated language after English and French (“Statistics on Whole Index Translationum Database”). Nevertheless, even though databases like the Index Translationum, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) and the German National Library (DNB) collect and provide access to bibliographic translation data, a comprehensive dataset that allows for the quantitative analysis of German literature in translation is still not available to researchers. This is surprising since the German National Library grants open access to the bibliographic data 22,232,147 of items (Sälzer and Schmitz-Kuhl 50), which makes it the most valuable resource for studying the corpus of translations produced in Germany.

Why then are we to date still lacking a dataset for translated German fiction? As I argue, one reason for this lack in datasets is in the invisibility of translation in national catalogues and the institutional practices regarding translations such as collection policies and cataloguing standards. While the translator’s invisibility is a much-discussed topic in translation studies (see Venuti; Rybicki), translation invisibility in national libraries or book reviews and its consequence on the availability and accessibility of translation data is a more recent topic (see Teichmann and Roman). How translations are catalogued and collected by national libraries has a significant impact to how we can find, extract, and use bibliographic translation data. Differentiating a translation from an original edition is the one of the main challenges when searching for translations of German fiction in the German National Library catalogue. Since translations are not their own category, they visually are not different from non-translated catalogue entries. For cataloguing, translations are treated as any other edition. In our recent article “Bibliographic Translation Data: Invisibility, Research Challenges, Institutional and Editorial Practices” (Teichmann and Roman) we argued that the fact that translations are not treated as their own category, both in book reviews and library catalogues highlights how cultural and institutional practices converge in the resulting translation invisibility.

Besides these larger implications for the status of translations in literary production, reception, as well as canonization, which lie beyond the scope of this article, translation invisibility results in significant challenges to extract bibliographic data from national libraries. Oftentimes translations in national library catalogues can only be identified based on a well-designed search query that includes a definition of what a translation is. E.g., if we want to find an English translation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis in a library catalogue, we will most likely search by the author’s name or the title and then get a list of all titles that correspond to our query. However, if we want to find all translations of Kafka’s works, we will receive hundreds of results, including his originals and secondary texts.[2] Poupaud et al. have described this central challenge of finding and extracting translations by narrowing it down to a matter of definition and filtering. Poupaud et al. assert that “the term ‘translation’ needs to be defined explicitly” (268) according to the prior filter and the research filter that give translation status to a given work of writing. A prior filter, for instance, may be institutional, as in the case of a library catalogue and collection where the selection and annotation process are handled on an institutional level. A research filter, on the other hand, is developed through the final selection of what is defined as translation by the researcher, which varies from project to project. Data extraction thus depends on how translation is defined and how it is applied as a filter. It is therefore necessary to transparently discuss the pre-existing and applied filters as part of documenting the collection and cataloguing practices on an institutional level and for curating the “Mapping German fiction in translation” dataset.

In this paper I address the following questions: How can we define outgoing translations in order to filter the library catalogue for translations and then extract their data? And how does this condition the data quality and representativeness? First, it is important to note that this paper builds on Reynolds and Vitali’s definition of translation as an “act of translation” that includes “both the first publication of a new translation and its republication in a different place” (Reynolds and Vitali 3), meaning that each title in the dataset is seen as a unique linguistic event and can therefore include various editions which may be reprints of an existing translation. Secondly, for the “Mapping German fiction in translation” dataset a translation is defined as a work which has been published in a different language than what it was originally published in. As part of my research filter, the bibliographic entry therefore always includes at least two languages: one source and one target language. As this paper demonstrates by evaluating data representativeness, quality, and reliability this definition has been proven to be effective in finding and extracting bibliographic data on translated German fiction from the German National Library.

In order to highlight the challenges and limitations of extracting translation data from the DNB the aim of this paper is to not only document the DNB’s collection and cataloguing practices in the light of the dataset curation process but also to provide researchers a set of various measures for data quality and representativeness to make visible the prior and research filters and contextualize them in the light of cataloguing practices. While the aforementioned challenges in finding translations in national libraries persist, introducing a reproducible definition based on cataloguing standards such as MARC allows for increasing the visibility of translations in our national repositories. By introducing the first bibliographic dataset of translated German fiction extracted from the DNB, I want to underline the importance of library data for translation, literary studies, and digital humanities. Such a dataset allows for exploring not only questions of translation invisibility but also to what extent the library is a “crucial institution in which world literature is defined, imagined, and redefined” (Mani 240), and a “place for knowledge production and collective knowledge” (Koh 385). In line with Mani and Koh, I have developed various tools and used the “Mapping German fiction in translation dataset”, to highlight women writers in translation (Teichmann, Visualizing German Women Writers’ Translations in Geographic Space), literary transfer (Teichmann, Casestudy on Geomapping Translations of German Fiction Extracted from the German National Library) of German fiction, networks of translation (Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation), and differences in the German and Austrian National libraries.

The extraction and documentation of the “Mapping German fiction in translation” dataset happened in four phases. After establishing inconsistencies across library catalogues and databases for bibliographic translation data, I designed a search query to extract the data from the DNB applying my definition of translation and compiled my final dataset. I then selected the main variables for my analysis and conducted a data quality assessment.[3]

The data quality assessment considers possible sources of bias to provide an overview of how representative the extracted dataset of German fiction in translation is, as well as to guide the reader through any data inaccuracies or inconsistencies that result from collection or cataloguing practices. In order to document the various biases of the applied filter on the relevant variables and the resulting dataset, I discuss four major categories of data quality assessment methods: consistency, sampling bias, accuracy, and completeness.[4] After presenting an overview of how representative the dataset source (the DNB) is in comparison to other major translation databases—comparing the selected records with the Austrian National Library (ÖNB), the Index Translationum (IT), and VIAF to review inconsistencies across datasets—this paper moves on to document collection practices and further evaluate the fitness of purpose for the dataset source. Additionally, a brief assessment of representativeness and bias was conducted by measuring falsely identified translations on a subset of data. For variables I assessed completeness (the amount of missing data) and variable accuracy, that describes the errors and data heterogeneity within the DNB translation dataset by measuring the ratio of data to errors for all relevant variables. The last section of this paper is dedicated to the challenges and limitations for applying the proposed extraction method to other national libraries.

Inconsistencies across databases: the DNB compared to the ÖNB, VIAF, and IT

As a pre-step to data curation, I evaluated how consistent or complete the translation data of the German National Library is compared to other resources for bibliographic translation data. To assess inconsistencies and estimate in what ways the data of the DNB may be missing records compared to other translation databases and catalogues, I compared the timeframe, the number of translations, and records for a selection of prominent authors in the German National Library catalogue (DNB), the Austrian National Library (ÖNB), the Virtual International Authority File database (VIAF), and the Index Translationum (IT).

As table 1 shows, the main challenge in assessing inconsistency lies in the different timeframes and scope of data entries. While in terms of the number of translations the IT appears as the most comprehensive resource, in April 2021 it did not include any data after 2012.[5] The IT mentions German as number three of the top 10 original languages with 208,240 translations documented between 1979 and 2019[6] – 2008 being the last year containing entries for German as a source language.[7] In comparison, the dataset analyzed in my thesis (extraction date: April 15, 2021) consists of 35,972 translations from German (fiction and non-fiction) in total between 1980 and 2020. While it is not possible with the current query function to assess the total number of translated titles for German, in 2017 VIAF had a total of 11,767 entries of works for German fiction in translation, representing not even half of the translations in the DNB for the years between 1980 and 2017 (34,863).[8] Not only do we see significant differences in the size of the databases—the IT appears to be a very comprehensive resource comparatively, while VIAF seems to not even include half of the translations in the DNB until 2017—the VIAF and IT’s differing timeframes do not allow for comparing the data. Due to a lack of a comprehensive report and documentation, it is only possible to roughly compare the datasets, which is why a closer look at a subset of data to highlight the caveats is necessary at this point.

When comparing translated editions in the DNB with ÖNB, VIAF, and IT for some prominent authors who have been originally published in German, we can get a sense of the dataset consistencies across different library collections and databases.[9] The Austrian author Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel Malina, for instance, appears with 34 entries of translations in the ÖNB catalogue and 51 entries of translations in the DNB dataset, which suggests that the latter is a more comprehensive resource, most likely because the novel was first published in Germany, and therefore most translations were registered at the German National Library. VIAF only lists eight entries for Malina: the Russian, Polish, Hebrew, French, and English translations are all part of one expression alongside the German original.[10] In comparison, the IT cites a total of 11 translations of Ingeborg Bachmann.[11] In summary, this suggests that the DNB includes the most records on Bachmann’s Malina, while other databases have less information, both in terms of catalogue entries and data categories available.

Another example that illustrates some of the data inconsistencies of these sources is Patrick Süskind’s novel Das Parfum (1985), which was first published with Diogenes in Zürich and received the PEN translation prize in 1987, as well as bestseller list status. The ÖNB only lists the Bulgarian translation from 2007,[12] while the DNB catalogue lists 106 translated editions among 20 publications in German and many schoolbook adaptations. VIAF lists nine translations (Arabic, three editions in English, Hungarian, Croatian, Korean, Polish, and Russian).[13] Again, similar to the previous example, the German National Library appears to include the most records for this prominent novel.[14]

The above examples show how inconsistent databases are and the related challenges of working with bibliographic data of German fiction. The biggest challenge in assessing inconsistency across databases and libraries is the lack of sufficient documentation, differing timeframes, and the restricted accessibility or availability of raw data. These examples nonetheless suggest that the German National Library is the most comprehensive and accessible resource for data on translations of German fiction[15] compared to VIAF and the IT, which currently do not provide open access to their data.

Data collection

The “Mapping German fiction in translation” dataset has been extracted from the Datenshop[16] of the DNB, which offers an online, free, (Creative Commons Public Domain) resource to query all bibliographic data of the library. From the Datenshop a set of data in CSV (comma-separated values) format[17] has been extracted for each year with publication dates between 1980 and 2020.[18] An expert search for each year of publication was conducted in order to filter the DNB catalogue for translations based on my definition: any work classifies as a translation that has been originally published in German while having another target language. The following line of Boolean search code extracts all works of fiction that originally appeared in German and then were published in other languages. In other words, it says: search for any work that has German as the original language (spo=ger) and limit all results to German literature (sgt=59) and fiction (sgt=B) for the year 2020 (jhr=2020).[19]

spo=ger and (sgt=59 or sgt=B) and (jhr=2020)[20]

With this query, the following catalogue entry can be identified:

With the above query, 35,972 titles of German fiction translations for the years 1980-2020 were identified and extracted. When looking at the total number of titles of fiction in the catalogue by using the same query omitting spo=ger, we can see that translations occupy 3.5% of fiction titles in the catalogue (n= 1,002,420 titles of fiction in all languages).[21] This result suggests that the search query has been an efficient method to extract translations from the DNB, however a closer look at a sample as well as the overall distributions is necessary to evaluate the quality of the dataset.

Translations in the DNB: Sampling bias, cataloguing and collection practices

In this section, I evaluate how successful the search query is in extracting translations from the DNB and examine the frequency of collected translations for different extraction dates (collection practices). This is important for establishing how representative the extracted dataset from the German National Library is in terms of its sampling bias and for documenting institutional practices, not only in collecting but also in annotating translations (cataloguing practices).

Sampling bias

In order to establish how confident we can be that the search query indeed identified all translations based on my definition, I measured the false positives for the year 2020, manually annotating false positives by identifying titles that have been extracted as translations from German but are actually translations from another language.[22] Based on the filter and definition of translated work, I manually verified all entries (n=552 from 35,972 total records in the DNB)[23] that can be identified as translations into German. However, outliers that can still be included are works in more than one language of translation, multilingual works,[24] and a small number of translations from English, which were published in Germany (3) and therefore selected. Additionally, translations from a German dialect (such as Plattdeutsch) are included. Anthologies of selected texts by non-German authors also appear among the extracted catalogued items. Only two false positives were found in the dataset for the entries marked as German.[25] Additionally, 65 (11%) of all extracted translations have a publication place in Germany. This is an especially interesting category since after close examination, most of these records are self-published translations and smaller publishers focused on translations. Overall, only the previously mentioned two translated works from English into German published by a German publisher can be identified as false positives. Based on this assessment of a smaller subset, it can be deduced that the definition and designed search query enable a comprehensive extraction of translations without adding data entries of non-translations in the data.[26]

Summary statistics illustrating cataloguing and collection practices

Besides defining a filter for extraction and establishing a definition of translation that reveals a reliable dataset, documenting collection and cataloguing practices is another crucial step when working with translation data from the DNB. It is important to note that works of translations are not consistently collected or identified as such across national libraries.[27] First, like most library catalogues, the DNB does not include a separate field to mark translations that clearly distinguishes translations from other editions. For the catalogue a translation is just another edition. When searching for translations hence, other fields need to be consulted, such as the language.[28] Besides the language field, the common indication that a work is a translation may appear as plain text (trans./Übersetzt von/übers./trad./ceviren/etc.) in another field and does not follow a standardized format. Irregularities like these, and the fact that translations are not categorized as such in the catalogue in a standardized way, are a drawback of current cataloguing practices and need to be investigated prior to data extraction. The abovementioned search query used to extract the dataset present a viable solution for this challenge.

Secondly, as identified by (Mäkelä et al.) and as the inconsistencies across data resources show, cataloguing practices vary and therefore result in gaps in bibliographic datasets. For instance, I was informed by the librarians of the DNB that the codes for language were not assigned before 1992. From 1992 onwards, they were assigned consistently to all Germanica and translated German works (cod=ru), and only from 2010 onwards to all publications; however, as part of their ongoing cataloguing work, they retroactively assign language codes to older entries. Hence, for certain years before 1992 the applied search query by original language may yield fewer results and therefore requires additional extraction at a later point in time. Therefore, for the “Mapping German fiction in translation dataset” first extractions were done in 2017, while the final dataset was compiled in April 2021,[29] leaving enough time to observe fluctuations in data for the years before 1992.

Lastly, inconsistency in collection practices (the rate at which translations are added to the collection) pose additional challenges and limitations for extracting and modeling the translation data of the DNB catalogue. While the legal deposit regulation ensures that translations are collected by the DNB, annual fluctuations in title data persist and visualizing the frequency distribution of title sums per year reveals collection practices, raising the question of whether the extracted dataset can support a longitudinal analysis. In order to show collection practices and how the extraction date affects the number of translated titles, I compare the title frequency distribution per year for two different extraction dates of the dataset (April 2021 – the last extraction date for the final dataset for the thesis – and May 2023– the most previous extraction date).

Comparing figure 3 and 4 shows that the date of extraction especially affects the years closest to that date. For example, figure 3, which shows the frequency distribution of translated titles per year in the DNB catalogue, reveals how the title count for 2020 is still very low (552 titles), even though the data was extracted in 2021.

Comparing figure 4 and 3 shows how cataloguing practices have affected the presence of translations for specific years. As we can see on figure 4, only one title has been added for the years 1980-1989 after the extraction in 2021. However, on both figures, the overall number of titles is increasing, especially from 2012 until 2016.[30] Lower numbers before 1994 may be correlated to the fact that language codes were assigned mostly after 1992 or to lesser submissions to the German National Library collection. For both extraction dates 2016 appears to be the year with most translations which again only shows that there were significant efforts to catalogue this year.[31]In summary, this comparison shows that the years closer to the extraction date have fewer translated titles; these titles are then added in the successive years. For the year 2020 a total of 381 titles have been added between 2021 and 2023. Accordingly, specific year ranges (especially around 2010 and dates within a range of five years before the extraction date) appear to receive a retroactive boost in their catalogued translations, it is important to take these fluctuations into account.

A second method to assess possible challenges related to collection practices is to measure how the number of translations compare to the overall number of translations in the catalogue, or in other words: How large is the share of translations in the DNB catalogue and how large is the share of fiction in translation vs non-fiction? This was done by calculating percentages of German fiction in translation in the library catalogue for each year and compare the overall distribution for different extraction dates. By comparing percentages of fiction with the frequency distribution of fiction and non-fiction, the space that translations occupy in the DNB becomes visible. As mentioned above, the number of outgoing translations in the DNB is at 3.5% of all fiction titles in the 2021 dataset. For the dataset extracted in 2023 out of 1,102,480 titles 403,55 were translations of German fiction, representing 3.6%, illustrating a slight increase in translated titles. Again, when comparing the percentage of translated German fiction to non-fiction titles in the DNB, we can see especially which years experienced an increase in collected translations.

Figure 5 shows that at the time of the extraction of the final dataset for analysis in April 2021, translated fiction has the highest percentage of all fiction in the DNB in 1997 and the lowest in the 1980-90 range and 2020 (the year closest to the extraction date). Again, considering that after 1997 numbers improved for fiction, this comparison also illustrates a general tendency in collection practices.[32] Extracting the data with the same query on different dates can hence also serve to document the collection practices of translations by the DNB and to observe shifts over time.

Comparing the percentage of translations in the DNB extracted in 2021 and 2023, we can see on figure 6 that for the years before 2017 the overall translation sums have not changed significantly. However, after 2017 translations have retroactively been added to the DNB. For 2020 for instance the percentage of translations has increased from 1.5% to 3.5%. This again confirms the previous observation that, especially for the years leading up to the date of extraction, the numbers are still shifting while for previous years they appear to have stabilized. Any analysis hence needs to consider the delay in collection practices, especially when applying longitudinal modeling of the data.[33]

Data quality of variables

Collection and especially cataloguing practices affect not only the title frequencies per year and representativeness of the dataset, but also the data quality of variables. This section is dedicated to the data quality and challenges related to each variable in the dataset.

Variables

Before measuring the data quality of each variable, it is necessary to introduce what type of metadata is contained in the catalogue and which variables are central to my analysis. The CSV tables extracted from the Datenshop contain metadata on the creator (author, translator, illustrator), title, publication year, publisher, and the publishing place amongst others.

For the data collection and analysis, “language”, “country”, and “creator” serve as the main variables. The language variable can serve as the main category for analyzing into which German fiction is most frequently translated (see Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation in the German National Library Catalogue, 82-90). The publisher field includes the publishing place, which is another variable in addition to the country variable that can be used for mapping and spatial analysis of the literary transfer of German fiction (see Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation in the German National Library Catalogue, 143-150). As mentioned in the previous section, cataloguing practices are not always consistent across variables, e.g., in the DNB metadata languages have been assigned retroactively after 1992. We therefore need to evaluate whether the variables central to my analysis – title, creator, language, country, and publishing place language – are complete (have few to no missing values) for all entries in the dataset. The following two sections are dedicated to evaluating how reliable those variables are in terms of completeness and error rates.

Completeness

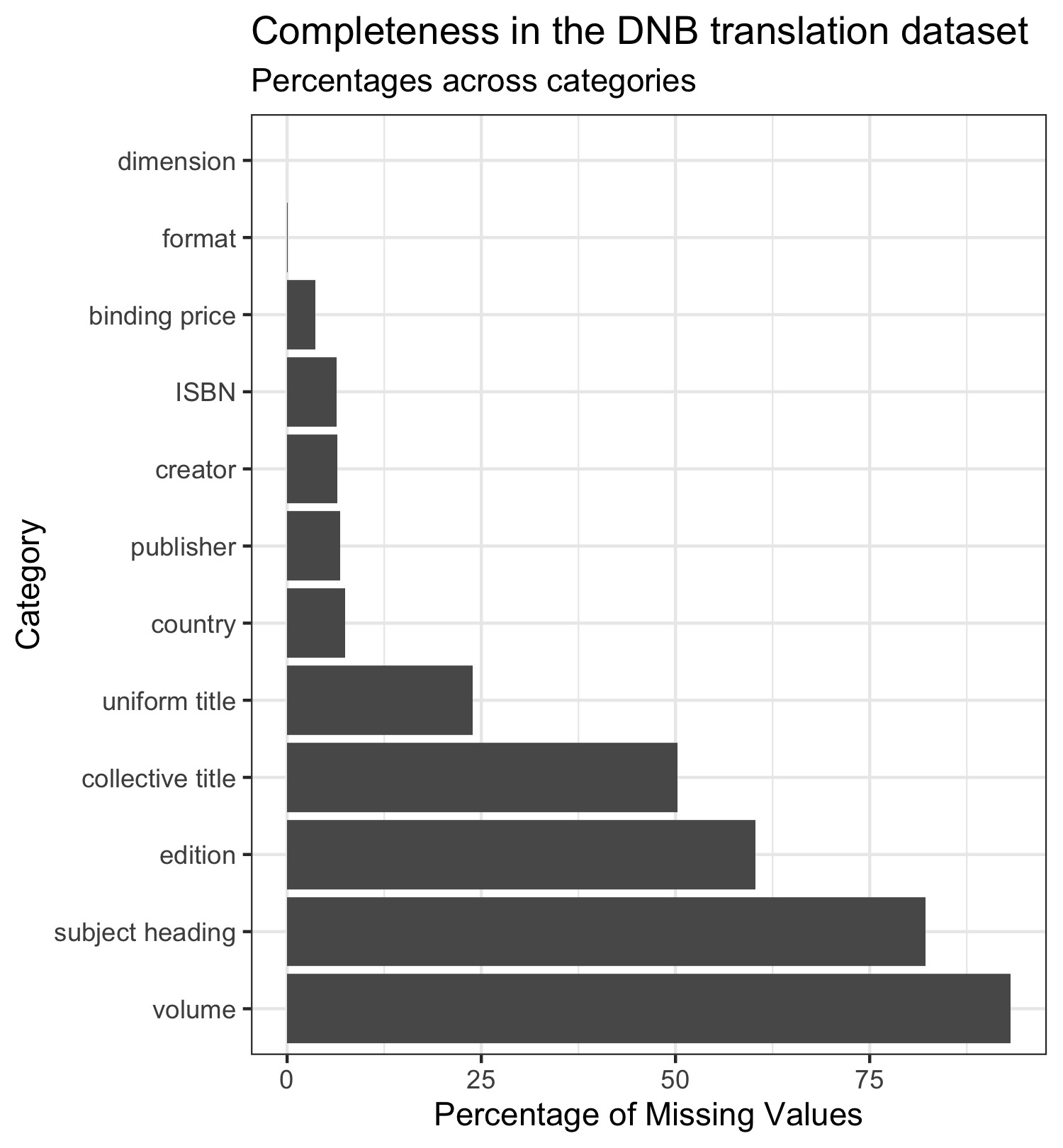

Completeness is assessed by counting missing values for each variable. As figure 7 illustrates, the most complete variables are publisher (6.9% NAs),[34] creator (6.5% NAs), country (7.5%), ISBN (6.3%), and format with only 34 missing values. Hence, measuring completeness shows that my central variables don’t raise major challenges.

Several categories have an increased number of missing values. Volume and edition appear as the two categories with the most missing values, with 93% of missing values for volume and 60% for edition.[35] Binding price appears to be a more complete category, with missing values for only 3.6% of all works. Additionally, collective title (i.e., translated title) with 50.2% missing values, subject headings with 82.2% missing values, and uniform title/original German title with 23.8% missing values are also categories with an increased number of missing values. Language and year (publication date) are the most comprehensive categories with no missing values. These numbers allow the evaluation of the limitations of each variable, and thus which variables can be reliably included in further analysis.

In summary, evaluating the completeness confirmed that the variables central to my analysis—title, creator, language, country, and publishing place—do not pose major limitations for analysis. However, additional data cleaning and aggregating needed to be done in order to prepare the data for analysis. The publishing place for instance had to be extracted from the publisher metadata before doing the geocoding and mapping. Likewise, the author had to be extracted from the “creator” variable, which also includes translators, editors, and illustrators. Additionally, due to the increased number of missing values for the original title (uniform.title), the analysis of this variable has only marginally been done (see Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation in the German National Library Catalogue, 148-149) and instead focuses on variables with few missing values such as author. As I discuss in the following section, some variables such as author names may raise additional challenges such as name ambiguity or variations that can represent sources of error for the analysis.

Sources of errors across variables (accuracy)

In this section I address the variables’ accuracy and by evaluating sources of common errors in bibliographic data identified in scholarly literature, which allows me to establish whether my main variables for analysis pose major challenges for their analysis. To assess data quality of bibliographic data, accuracy is defined as the ratio of correct and incorrect values with a focus on sources of errors mentioned by previous studies on bibliographic data (Olensky 22–23). According to Olensky, areas of concern in data accuracy for bibliographic data are: inconsistent and erroneous spellings of author names, author names with accented characters, names with prefixes, double middle initials with or without punctuation, misspelling of author names with many adjacent consonants, various abbreviations and punctuation in journal titles, and lack of journal title standardization of the numeric bibliographic fields (publication year, volume number, pagination). The variations of an author’s name are one of the main identified sources of errors according to Olensky, while standardization in each bibliographic field is also an issue.

To get an estimate of all unique values, authors’ names have been extracted from the “creator” column[36] and then aggregated to identify possible ambiguities. The process wielded 6,457 authors with 4,963 unique author names[37] that are coherent in orthography and not ambiguous. Only two authors’ names were not identifiable, which suggests a high object-level accuracy for the author field.[38] According to the German National Library’s cataloguing practices, authors have a standardized format which ensures that they do not include variations in spelling. Accordingly, the authors’ names appear to not pose significant challenges when modeling this variable.[39]

For all other variables, I examine accuracy across a random sample of 100 catalogued items with attention to publication place, language, and country codes.[40] When looking at the accuracy for each variable, I found that sometimes two publishing places are included, only for one of which the country code matches (typically the first one). The publisher field also includes place names, which are erroneously or inconsistently used, such as Barcellona and Barcelona. Additionally, several place names include the country of publication as well, while others do not, posing challenges that require solutions such as fuzzymatching or string detection and grouping of place names (see Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation in the German National Library Catalogue, 142).

Similarly, language is also a category with very few errors, whereby only eight entries are marked with “und” or “zxx”, meaning that the language has not been identified. Language is also the most complete category, with no missing values.[41] However, some categories have specific properties. Here is an example which shows language as “ger” (German) while the title is actually in Dutch:

For the record in figure 8 we have a publisher located in the Netherlands and in Belgium; however, only the latter appears in the country field. Similarly, for language, the catalogue only includes German and not Dutch. This appears to be a bilingual publication, based on the publication place and country information.[42] These types of entries make up approximately 3.6% of the whole dataset for which the language is German with another language that is not marked, and is therefore treated as their own language category.[43] Additionally, my definition of translation—a work with differing target and original language—also naturally includes any bilingual (“ger”) and multilingual (“mul”) publications for which German is at least one of the languages.

In summary, author name, language, and country appear to be accurate and consistent variables, and hence can be used for further analysis of the complete dataset. Assessing possible error sources for the main variables of analysis was not only necessary to develop strategies to tackle related challenges and limitations, but also to document how representative, complete, and accessible the German National Library’s bibliographic translation data is.

Conclusion and outlook: working toward a catalogue snapshot repository

Consistency, accuracy, completeness, and sample bias provide insight into the limitations and challenges of the dataset, as well as which variables appear to be reliable sources of information for further analysis. By measuring consistency, accuracy, completeness and sample bias, the following can be concluded: first and foremost, the DNB is one of the most comprehensive resources for bibliographic translation data for German fiction, but in order to extract translation data, a definition of what constitutes a translation needs to be formulated and an expert search designed accordingly. Secondly, as opposed to the literature on common sources of errors in bibliographic data, author name ambiguity does not appear to be a major challenge since the DNB follows orthographic standards. In other data variables, such as language, erroneous data are below 0.1% of all cases, resulting in a high-quality dataset for analysis. Third, incomplete data is a minor challenge that can be solved by splitting data in columns such as “creator” to extract author and translator names or substituting some variables such as country with information from other fields. The most problematic variables in terms of missing value such as edition, volume, and subject heading are not central to the analysis. Lastly, bilingual and multilingual works require additional annotation of languages.

As the aforementioned numbers show, in order to support claims about a library collection, it is necessary to assess the representativeness of the dataset by documenting biases, errors, and scope of the analyzed data (see Mocnik et al.; Pechenick et al.; Mäkelä et al.). For bibliographic datasets of translation, the bias is often defined by the dataset selection or sampling criteria on the one hand—for example, prestigious authors, such as prizewinners (see Pechenick et al.)—and collection-specific bias on the other. The latter, for example, has resulted in previously “unreported bias” (Lahti, Mäkelä, et al. 287) within Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO), which in turn lead to the repeated underrepresentation of specific aspects of literature of this period within scholarship using this dataset. Especially for widely available resources, such as Google Books, which are biased toward prestigious authors and published alongside tools such as the ngram viewer to visualize keyword frequencies in the corpus, the question of representativeness in relation to the dataset quality and bias is important to take into consideration. Mäkelä et al. point out regarding projects in the digital humanities, “without facilities for acknowledging, detecting, handling and correcting for such bias, any results based on the material will be faulty” (Mäkelä et al. 82). This is why scholars of the digital humanities, bibliographic data analysis,[44] and literary studies recommend assessing, documenting, and most importantly accounting (Pechenick et al. 12) for the data quality, sample bias, and the overall representativeness of bibliographic datasets. This data quality assessment hence is an attempt to evaluate the unreported bias’ of national libraries due to their cataloguing and collection practices and to document the potential of the DNB as a source for translation data.

However, there are no best practices or standardized methods established yet for translation data specifically, and methods proposed by scholars working on bibliographic data are mainly focused on scientific journal data (see Van Kleeck et al.; Olensky; Demetrescu et al.),[45] which raises its own challenges regarding the applicability of the proposed data quality assessment methods to translation data. The common point of these approaches is to first identify the possible sources of bias. For bibliographic data, for instance, some sources of bias, inconsistencies, and inaccuracy have been identified as author name ambiguity due to MARC cataloguing standards, multiple editions not being linked, and collection bias, alongside cataloguing practices which create gaps in certain periods (see Mäkelä et al. and Lahti, Mäkelä, et al.). In this data quality assessment and description of the dataset, previously documented challenges are considered while also proposing solutions for developing best practices in curating bibliographic translation datasets from national collections.

The workflow presented in this paper for tackling these challenges documents the extraction and curation process, as well as possible solutions to working with translation data from the German National Library. Hence, the proposed methods range from formulating an expert search based on a definition of translations to simple frequency counts, and any findings shall be disclosed in a field guide for other researchers interested in the dataset. This is especially important since, too often, “decisions about how to handle missing data, impute missing values, remove outliers, transform variables, and perform other common data cleaning and analysis steps may be minimally documented” (Borgman, Big Data, Little Data, No Data 27). As I argue, clearly defining what a translation is in the context of the data source (here the DNB), documenting the data extraction process, and assessing challenges and reliability of data quality are necessary steps toward building a dataset for analysis.

Additionally, this paper proposes a reproducible workflow for the extraction of translations to compile a repository of datasets for translations that represents snapshots of the catalogue in different points in time. With the same search query based on original language, German, datasets for different dates have been extracted in 2021 and 2023 to document and compare collection practices and their shifts over a period of time. The resulting datasets which are published alongside this paper are the fundamental building blocks to assemble a repository of datasets that allows researchers to analyze translations at a given point in time in the collection while also analyzing the archive as a whole over time. In that regard the work for which this paper is only the beginning may be of interest not only to literary scholars but also to critical archival and information science researchers as well as book historians for examining how cataloguing and collection practices change over time, how national library collections evolve and what this reflects on the field of translations and their importance in a literary culture.

Compiling these first datasets for German fiction in translation from the DNB and my discussion on inconsistencies across catalogues as well as databases such as the IT or VIAF also compels us to think about possibilities to apply some of the proposed extraction and data quality assessment to other bibliographic data sources. In line with Borgman’s call for more transparent documentation and Tolonen et al.'s work toward a standardized workflow and documentation of data harmonization for library datasets this paper is but the beginning to analyze bibliographic data across national libraries by developing a reproducible workflow to extract bibliographic data from the DNB and therefore make translations visible in the library.[46] How we can operationalize extraction and systematically document cataloguing and collection practices and data quality is still a challenge when applying it to various libraries. Besides further building a snapshot repository for translation data in the DNB, a future step of this project is to test the definition and query to identify and extract translations from other libraries such as the ÖNB, the Swiss National Library, or the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). This would enable us henceforth to study translations across different national collections. This paper, I hope, provides initial steps in the direction of providing researchers with the tools to access, extract, and use the wealth of bibliographic translation data that is available. Additionally, I hope this paper contributes to a more general discussion on the status of translations in regard to institutional practices by contextualizing cataloguing and collection standards in the DNB and the ways in which researchers can help make translations visible in our national libraries.

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LJFLL9

This paper is based on my thesis. (See Teichmann, Mapping German Fiction in Translation in the German National Library Catalogue) Parts of this paper have been presented at the annual conference of the Canadian Association for Translation Studies in May 2023 in Toronto and the conference of the Association for Digital Humanities 2023 in Graz.

Christine Borgman argues that one reason why library catalogues are hard to use is that it requires to know exactly what one is looking for: “Query matching is effective only when the search is specific, the searcher knows precisely what he or she wants, and the request can be expressed adequately in the language of the system(e.g., author, title, subject headings, descriptors, dates).” (Borgman, “Why Are Online Catalogs Still Hard to Use?” 494)

The quality assessment presented in this paper is predominantly on the dataset analyzed in my thesis (extraction date: April 15, 2021). The datasets extracted in 2021 and 2023 serve to compare the results of the data quality assessment and to illustrate collection practices.

(Olson 24–42), whose assessment of data quality and bias included the following: value representation consistency (varying orthography), changed induced inconsistencies (changes in the way the data has been recorded), valid values (value is accurate and consistently used), missing values, object-level accuracy (if objects are missing in database, appears to be complete but is not), and object-level inconsistencies (fluctuations in changes made to the dataset by removing or adding data).

At the time of data curation (January 2019 until April 2021), the Index Translationum web portal was under construction and no assessment could be made on the variables in the dataset. An initial extraction in 2017 showed that the dataset did not include work titles or publication year and publisher information, but only raw counts of translation numbers into each language.

Since April 2021, the IT has included a “Last Updates” page with information about the time and amount of data deposits. It indicates that for German the last received year is 2019, while “2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 currently being processed by the INDEX team.” (“Contributions from countries”)

According to the catalogue accessed on 18 Dec. 2023.

The presented numbers refer to the translations catalogued until August 2022. They may vary for later dates, since translated editions are continuously being added to the catalogue.

(“Bachmann, Ingeborg, 1926-1973. Malina” n.d.)

The IT only includes author name and translation frequencies per language, which complicates tracing single works.

The Swiss National Library catalogue does not contain any translations for Süskind’s Das Parfum.

One of the main reasons that the DNB is a rich resource for translation data is their collection policy, according to which any printed or digital work originally published in Germany (which includes translations) as well as any works on Germany (Germanica) need to be submitted to the library (see the section “Sammelpflichtige Veröffentlichungen aus dem Ausland” in (“Unser Sammelauftrag”)). The legal deposit regulation (PflAV) specifically includes “media works published abroad for which a publisher or a person who has a legal domicile, business premises or their principal residence in Germany has sold (licensed) the right to publish the work abroad”, Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) § 17 Auskunftspflicht: “Die Ablieferungspflichtigen haben der Bibliothek bei Ablieferung der Medienwerke unentgeltlich die zu ihrer Aufgabenerfüllung notwendigen Auskünfte auf Verlangen zu erteilen. Kommen sie dieser Pflicht nicht nach, ist die Bibliothek nach Ablauf eines Monats seit Beginn der Verbreitung oder öffentlichen Zugänglichmachung berechtigt, die Informationen auf Kosten der Auskunftspflichtigen anderweitig zu beschaffen.” (“Sammlung Körperlicher Medienwerke”)

One set of bibliographic records may not exceed 10,000 entries and a user can conduct 200 queries.

Additional options for formats include MARC, which requires transforming the data into tables by using a Python script. Hence, CSV was the most accessible format to use in RStudio for the proposed model. In the dataset the original data structure and format have been conserved so that any accompanying scripts can be run on datasets extracted at a later point in time or comparing findings for datasets extracted in 2019, 2021, and 2023.

In 2020, numbers for that year were still very low (64 book titles in May) relative to the average amount of titles per year, which is why the final dataset for 2020 was extracted in 2021.

In order to collect incoming translations to study the role of translation in the German publishing landscape, a different method would need to be developed that includes conditions as to the work being originally published in another language as German, but published in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland. This can be achieved by simply designing a similar search query that follows the same logic as the one used for this dataset, e.g., “geo=de and spo=eng and spr=ger and sgt=B” where “geo” selects works published in Germany, “spo” selects the original language and “spr” again selects publications in German.

spo" stands for original language, “sgt=59” for German literature, and “sgt=B” for Belletristik (fiction).

When applying the query mentioned above for incoming translations, we can see that they are significantly more present in the catalogue with 114,969 titles of fiction corresponding to 11.4% of all fiction titles.

A comprehensive analysis of precision and recall would require having a comparable dataset with complete, consistent bibliographic data in the same categories as the DNB. As discussed in this paper, due to data inconsistency in translation datasets, this lies beyond the scope of this project. For the same reason, an assessment of false negatives is not included here.

See file in data repository: dnb-datashop_ger_2020_precision.cs"v

Such as Deutsche Gedichte zweisprachig: Kurmanji-Kurdisch/Deutsch / herausgegeben und übersetzt von Abdullah İncekan which was marked as German.

When measuring precision for a random sample of 100 titles, only two titles were identified that are not translations, further confirming the first finding. See file: alldnb_random_sample_precision_ch2.0.csv.

To assess false negatives, a classification of all records would need to be done on a total of 100,545 titles (translations included) in the fiction category, which at this current point in time lies beyond the scope of this study.

One question I asked myself was if I could combine the DNB dataset and Austrian and Swiss catalogue data. However, in the case of the Austrian National Library, a large-scale extraction of translation data is challenging because the collection Austriacae only includes all Austria-related publications (“Katalog”). A Python script for extracting MARC data from the ÖNB however exists and as part of future work can be adapted for translations. See https://labs.onb.ac.at/gitlab/labs-team/catalogue/-/tree/master

The MARC entries include a field (41) that indicates the edition’s language. Subfields 41ǂh then indicate the original’s language (“041 Language Code (R)”). This appears to be consistent across catalogues and also true for the ÖNB catalogue data. The search query used to extract my dataset by original language apparently draws on this field and the DNB intentionally also includes this information in the catalogue search and query functions which makes it possible to identify and extract translations. For other catalogues such as the ÖNB this is not the case and translations are less visible or easy to extract by querying the catalogue.

As stated on the library’s Datenshop page, metadata is constantly being updated, which may lead to varying numbers of titles and therefore requires running any statistical testing on the most recent dataset.

For frequency counts per year see: alldnb_2021_titlesums_peryear.csv and alldnb_2023_titlesums_peryear.csv in the data repository.

This has been confirmed by the librarians of the Datenshop.

When comparing numbers of fiction with non-fiction we can see that for specific years (such as 1997 as compared to 1993), publications of translations of fiction versus translations of non-fiction do not overlap. 1997-2000 have by far been the best years for collecting translations of fiction, while for non-fiction that period came earlier (1992-1994).

A longitudinal analysis of this data therefore requires a larger window between extractions (minimum three years) and hence lies beyond the scope of this study.

NA stands for not available and therefore for missing values.

Dimensions are missing for 7.7% of all entries; in contrast, for weight, data is missing for 99% of entries.

In the “creator” column of the DNB’s CSV data the author’s name precedes “Verfasser” (see the first column in table 3). This annotation has been used to extract the authors’ names.

For 6.4% of titles the author value is missing, and 48.9% of all titles have missing values for translator.

Author names: “3010!1102173592!”; “-ky”

For titles, however, 5% appear to be not unique, meaning that they do not follow a standardized format. Considering that the title variable varies according to the edition’s language and also includes information on the translator and the original title, accuracy is difficult to assess. There is no procedure to assess the accuracy of work titles, since they are a unique set of strings which would need to be validated with an external dataset. Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that most of these 5% only include information on edition and not the title.

Several variables have problematic levels of accuracy, such as volume, edition, and publisher. Volume, edition, and publisher are categories that include more ambiguity compared to language, title, and author. For volume and edition, erroneous values mostly result from ambiguous categorizations, especially of editions. Edition and volume information is included in each work’s target language (e.g., Bd. 1, ed. 1, 1. Aufl, etc.). Additionally, volume also includes the original titles and translated titles. Data of these categories is too inconsistent to give an estimate of accuracy. See file: alldnb_random_sample_precision_ch2.0.csv.

Besides the relevant variables, format is also one of the most accurate and complete categories, including information on page numbers, dimensions, and weight. However, the orthography is not consistent and for each unit, there are a number of variants (e.g., Seiten, pages, S., gr., g, Gramm).

Same for: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/847838967. Additionally, some online resources list Germany as country: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027479955.

According to statements from researchers at the Datenshop, the category “ger” in the language field has only been used after 2007, which is why it only affects catalogue entries from after that date.

Lahti et al. define Bibliographic Data Science as follows: “Bibliographic data science derives from the already established field of data science. It associates this general paradigm specifically with quantitative analysis of bibliographic data collections and related information sources. While having a specific scope, BDS is opening up pragmatically oriented and substantial new research opportunities in this area, as we have aimed to demonstrate” (Lahti, Vaara, et al. 18).

Van Kleeck et al. propose a comparison with another database as reference and to assess completeness (e-resources only). Olensky assesses differences in data quality between journal platforms such as WOS and Scopus, while Demetrescu only focuses on journal articles.

Tolonen et al. emphasize to highlight aspects of data by visualizing document dimensions, publication years, author life spans, and gender distribution based on timelines, scatterplots, and histograms to identify outliers and possible biases in the dataset. Besides documenting data harmonization and analysis efforts, they propose natural language processing, feature selection, clustering, and classification as methods to control for duplicate entries, inaccuracies, and errors in bibliographic data.

_from_the_german_national_library_(all_translated_wor.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(all_translated_wor.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(all_translated_wor.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(all_translated_wor.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(.png)

_from_the_german_national_library_(.png)