1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the reception of Classics in Early Modern England during the hand press era, concentrating on printed documents between the 1470s and 1790s. Starting from a research interest in the reception of classical works, we aim to enhance our understanding of the processes involved in canon formation and the transmission of knowledge. Among other things, our analysis reveals an intriguing cultural transformation in the 18th century: while the total number of printings of classical authors increased, there was a noticeable decline in authorial diversity. This phenomenon reflects broader shifts in cultural formation during this era. We explore the benefits of the integration of digital archives, as a complement to earlier research, which was predominantly conducted without the assistance of digital technology. In doing so, we contribute to the growing field of quantitative book history (Suarez; Buringh and Van Zanden; Lahti et al.). Before presenting our data (Section 2) and the results obtained (Sections 3–4), we present a survey in which we outline how our aims relate to the state of the art (Section 1.1).

1.1. State of the art and aims

The notion of canonization — i.e. the process for which some literary texts are singled out as exemplary or noteworthy — is the object of extensive publications and discussions (see for instance Altieri; Bloom, The Western Canon; Calvino; Guillory; Moretti). Its impact on the teaching practice notably stirs controversy (Bloom, How to Read and Why), as does its tight relationship with the social and political phenomena (Bourdieu; English). In this research area, the ‘afterlife’ of classical texts is the object of a number of established strands of inquiry, most notably the study of the classical tradition (Kallendorf, A Companion to the Classical Tradition; Grafton et al.) and classical reception studies (Martindale and Thomas). The circulation and canonization of Classics are umbrella–terms that cover a broad array of phenomena, which can be examined from multiple perspectives, and often entail a variety of sensitivities and controversies that fall outside the scope of this paper (see e.g. Jenkins 21–22; Lamers 27–28 for further references). Kennedy’s “The Origin of the Concept of a Canon and Its Application to the Greek and Latin Classics” provides a high-level overview of the complex process of loss, discovery and establishment of a set of classical authors which were read, studied, and published across the centuries.

The same complexity can be observed in specific time-periods and countries. For England, the monumental five-volume publication of The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature reflects the multiplicity of points of view from which the question can be tackled. The field, even when narrowing it down to 17th and 18th century Britain, is vast.

Several scholars focus on the reception of specific classical authors in British culture. Some monographs stand out: for instance, the case of Homer (Clarke’s A Historical Introduction to the Iliad and the Odyssey and Simonsuuri’s Homer’s original genius: eighteenth-century notions of the early Greek epic 1688–1798)[1] and the reception of Virgil, Homer’s Latin counterpart (Thomas’ Chapters 4 and 5 of Virgil and the Augustan Reception, and Hardie’s The Last Trojan Hero: A Cultural History of Virgil’s Aeneid). Lord’s Classical Presences in Seventeenth-Century English Poetry and Ogilvie’s Latin and Greek: A History of the Influence of the Classics on English Life from 1600 to 1918 provide a more general overview of the presence of Classics in Early Modern Britain[2].

Equally ubiquitous are studies detecting the influence of Classics on writing and thought of modern authors. For English literature, the most popular cases appear to be Shakespeare and Milton, and the writers and translators Dryden and Pope (cf. the chapters dedicated to Shakespeare, Milton and Dryden in volumes 2 and 3 of The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature, and Hopkins’ chapter on Homer in volume 3).

Finally, several studies approach the societal aspects of the presence of Classics in later contexts: for Early Modern England, the place of Classics in the curriculum in Britain grammar schools has been studied in the seminal work of Baldwin (William Shakspere’s Small Latine and Lesse Greeke) and Foster (The English Grammar Schools to 1660), while Wilson, “The Place of Classics in Education and Publishing” discusses how the printing and teaching activities show the tension between the expansion and canonization in the circulation of Classics. Directly linked to the educational dimension is the role of translation for the circulation of Classics (Lathrop, Translations from the Classics into English).

This paper aims to complement this genre of meticulous scholarship, along with the myriad articles that accompany it, by exploring whether we can offer a panoramic, bird’s-eye view of the issue. To the best of our knowledge, a thorough exploration of what Jan M. Ziolkowski refers to as ‘shifting canons’ has yet to be undertaken (Ziolkowski 22): we therefore aim at quantitatively mapping the fluctuating perceptions of the classical canon across different time periods and regions.

This paper assumes that bibliographic metadata catalogues can serve as tools for investigating the emergence of a canon of ancient authors in Early Modern Europe (Tolonen et al., “Examining the Early Modern Canon”). Most of the analysis targets the 17th and 18th centuries, due to the larger availability of data stemming from the rapid increase of printing in these two centuries (Febvre and Martin). The datasets on which we rely, described in detail in Section 2, have a specific focus on publishers based in Britain. As a result, this paper does not take into account the import of books from abroad (e.g. France and Low-Countries), even though it is well-known that this played a substantial role for the English market (for references, cf. Hosington 3, n.1).

Section 3 tracks the printing of Classics in Early Modern Britain, focusing on the evolving fortune of classical authors. How many authors were printed; did this number change significantly over time; and can we identify rising stars and forgotten authors through metadata analysis? We systematically refer to studies on the fortune of the (groups of) authors discussed, to embed the data analysis in the deeper understanding of the cultural trends identified by previous scholarship.

Section 4 presents the results of analyzing the language in which Classics were printed, based on the available metadata and manual enrichment of the data. In this way, we disentangle the circulation of Ancient Greek and Latin works, also from a (socio)linguistic perspective and we complement the studies on the role of translation in the classical tradition.

In the Conclusions, we discuss the limitations of our approach, while briefly introducing some complementary methodologies which could shed additional light on the questions discussed in the paper.

2. Data

This paper relies on three distinct data archives, each with its unique characteristics and significance.

The English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC)[3] is a comprehensive resource, including metadata on early books, serials, newspapers, and selected ephemera printed before 1801. It covers materials from various regions, including Britain, Ireland, British colonial territories, the United States, and items with substantial English, Welsh, Irish, or Gaelic text. The ESTC amalgamates multiple catalogues, resulting in a total of more than 480,000 records. Despite some potential issues, it is a valuable tool for investigating historical publications and their availability in libraries worldwide (Tolonen et al., “Examining the Early Modern Canon”).

Early English Books Online (EEBO)[4] constitutes a digital compilation of early printed works from 1472 to 1700, originating in England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and British North America (ca. 146,000 records). EEBO-TCP, or the Text Creation Partnership, has transcribed roughly 50% of these texts into machine-readable format. Although the initial transcription process introduced certain biases such as a preference for canonical works, EEBO-TCP made its transcriptions publicly accessible for research in 2020 (Gavin, “How To Think About EEBO”; Gavin, “EEBO and Us”).

Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) is a digital database exploited by Gale-Cengage (Gregg; Tolonen et al., “Anatomy”)[5]. It grants access to the full text of an extensive collection of 184,536 titles published between 1700 and 1800. ECCO stands out as one of the largest online repositories of eighteenth-century materials available to academic institutions, opening new venues for textual research (Tolonen et al., “Corpus linguistics”) and significantly influencing how researchers explore this historical period. The entire set of ECCO texts has been transcribed with Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

EEBO and ECCO have been linked to the harmonized ESTC, and the metadata of the three datasets enriched (Lahti et al.). To identify classical works in the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC), we followed a two-fold approach. First, we exploited biographical information available in the ESTC “actors” database (Tolonen et al., “Examining the Early Modern Canon”). We looked for authors writing in Latin and Greek of which either the date of birth or death was prior to the 6th century AD (as a conventional end date for Late Antiquity). The resulting list, manually checked, contains 294 authors. A second approach relied on existing authority lists for the classical world. Trismegistos Authors (TM Authors)[6] provides a comprehensive gazetteer of ancient world authors (800 BC – AD 800), at the time of writing 7374 entries (October 2023). It is based on authority files and metadata such as the Leuven Database of Ancient Books, PHI Latin, TLG, Pinakes, Wikidata, Perseus Catalog, etc. Of these collected authors, 3326 are dated to a period before the 6th century AD. We matched the VIAF IDs, present in both ESTC authors’ database and TM Authors, but the number of authors retrieved in this way (only 258) was unexpectedly lower than the number obtained using the previous approach. An examination revealed that 45 authors appeared only in the “Trismegistos list”, and 80 only in the list based on ESTC biographical information. The differences between the two were mostly explained by i) the presence of multiple VIAF IDs for the same individual[7]; ii) the lack of a VIAF identifier in either ESTC or Trismegistos; iii) the omission of an author in TM Authors, which is often due to differing interpretations of the concept of authorship (e.g., Jesus Christ is considered an author in ESTC but not in Trismegistos[8]). The two lists were manually checked and subsequently merged, providing a total of 312 classical authors attested in ESTC[9].

Subsequently, the classical authors’ IDs were mapped to the corresponding works, and from there to their EEBO and ECCO identifiers, which are used for Section 4. No text-mining was carried out on the titles of the works. As a consequence, the records are mostly editions and translations of ancient authors. Monographs and commentaries on ancient authors are rare in the dataset. An example is the work “Aristarchus Anti-Bentleianus quadraginta sex bentleii errores super Q. Horatii Flacci odarum libro primo spissos nonnullos, et erubescendos” by Johnson Richard. Since ESTC does not list Horace as an author, it is rightly excluded from the database. Unsurprisingly, however, our data retrieval reflects some inconsistencies in the ESTC metadata. For instance, for the book titled “A modern essay on the tenth satyr of Juvenal” (ESTC ID: R22431), Juvenal is listed as an author by ESTC, against its general policy. For consistency, in this paper we refer to the ESTC records associated to Ancient Greek and Latin authors as “classical editions”, or “editions of classical authors”. One ESTC ID corresponds to one edition (and not to one extant copy) of a work, and for multi-volume editions the same ID is assigned to all volumes. “Editions” in our usage include both texts in the original language and translations. A distinction between the two categories is made in Section 4. When multiple ancient texts are published or translated in a single work, the classical authors often remain anonymous, for instance in the work “Poetical translations from the ancients. By Gilbert Wakefield, B.A” (ESTC ID: T98000), where only Wakefield is mentioned as author. On the other hand, when classical authors have been listed in the ESTC “actors” database, they have been retrieved. An example is ESTC ID R21069, “Miscellany poems in two parts: containing new translations out of Virgil, Lucretius, Horace, Ovid, Theocritus, and other authours: with several original poems by the most eminent hands / published by Mr. Dryden”, where the five Latin authors are listed. There may, however, be inconsistencies in annotation on this level as well. Moreover, anonymous works are potentially not retrieved with this approach. To account for these, we exploited the Trismegistos Authors database, that lists “Anonymous authors” up to the 8th century. A manual check of the main entries revealed that the works had effectively been retrieved, because they were assigned to a ‘fictitious’ authors in the ESTC[10]. Hence, the impact on the total results should be minor[11].

Table 1 shows the number of classical editions (i.e. the number of ESTC IDs) retrieved for every collection mentioned. When discussing EEBO and ECCO, we keep as unit the ESTC-ID, because EEBO and ECCO apply different criteria to assign identifiers (e.g. for multivolume editions in ECCO, every volume received a different ECCO identifier).

In Section 4 we will use the language information newly annotated for the ECCO dataset only (for feasibility reasons); moreover, we aim at assessing the feasibility of the study of full text of printed books, which is available for EEBO-TCP and ECCO-TCP collections and not for the full ESTC. It is therefore important to assess how well ESTC classical editions are represented in EEBO and ECCO-printed books.

Table 2 compares the numbers of EEBO and ECCO with those of ESTC records corresponding to the time periods covered by each of the databases. ECCO’s representativity is rather stable across time, while that of EEBO fluctuates until the mid 16th century[12].

While the representativity for EEBO is rather good, Table 2 shows that 35% of the books are missing from ECCO, while only 25% is present in EEBO-TCP. In Section 4 we disentangle this information based on languages.

3. Classical Texts and Authors in Early Modern Britain

In this section, we describe trends in the printing of Classics from the 15th century to the end of the 18th century. We use the ESTC metadata to provide a general overview of the classical editions circulating in England. Our focus is on their overall impact on the printing activity in Britain (Section 3.1), on the diversity of the authors printed (3.2), and on the changes in the set of authors printed (Section 3.3).

3.1. The number of classical texts published

As explained in Section 2, we selected cases in which ancient writers were indicated as the work’s authors.

A first finding is the steady increase of ‘Classics’ editions across time, as can be seen in Figure 1.

This growth, however, largely results from the growth of book printing in England. When normalized against the total number of ESTC publications per decade, the proportion of Classics publications actually decreases from the 16th to the 18th century, as visible in Figure 2.

For the incunabula the percentage is at first sight much higher than for later periods, but a note of caution is in order due to the sparsity of data. According to Jones, the print of classical authors represented up to 10% of the total printing activity at the early stage of the printing “revolution” (up to 1500) in Italy, but in England it would only be 2.8% (Jones). This figure is in line with our findings for the period up to the first half of the 17th century, when the proportion of Classics ranges between 2.5% and 5%. This period corresponds to the English Renaissance, during which Classics played a major role (Mack). Except for a brief resurgence in the mid-16th century, the ESTC figures show a steady decline in proportion. The sudden drop around the year 1640 can be attributed to the outbreak of the English Civil War, which disrupted the publishing industry and redirected its focus toward the production of war-related pamphlets (Tiihonen). From approximately 1650 to 1750, the observed values stabilize around 2%, after which another decline becomes evident. Overall, as the printing industry takes off in England, the corpus of classical works loses prominence among the circulation of printed material.

3.2. The diversity of authors published in Early Modern Britain

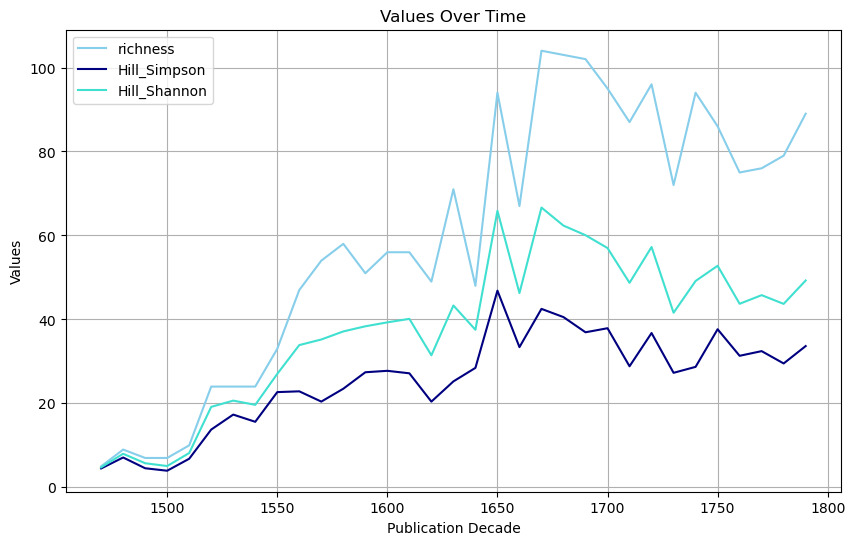

Despite a growth in the total number of publications, a diachronic analysis of the number of different authors published per year shows that initially it correlates with the increase in the number of publications, but in the second half of the seventeenth century it stabilizes (Figure 3).

The number of different authors is known as the “richness” (in terms of authors) of the set of publications that we are analyzing. In ecology, several indexes are developed that capture the variety of species within an observed sample, by taking into account not only the total number of different species, but also the proportion that each different species represents on the total of the community (its abundance). The difference between richness and diversity can be explained with an example: if two datasets of 100 editions feature two distinct authors, the richness of both datasets will be 2. However, if for one dataset, 90 books are attributed to one author and 10 to the other, while for the other dataset the ratio is 50/50, the diversity values will differ, the second dataset being more diverse than the first.

Two well-known indexes for diversity are the Shannon and Simpson index (Magurran). Metrics assessing this kind of information can be applied to collections of cultural artefacts (Kestemont et al.). Here, we compare the trend of three metrics across time:

-

Richness: already visualized in Figure 3 (blue line), simply counts the number of different authors published every decade. This measure has several drawbacks, the most important being the fact that it is highly sensitive to sample size. Since in our case the amount of books per decade significantly increases over time, the change in size impacts the results.

-

The Hill-Shannon diversity index (Roswell et al.) takes into account the relative abundance of the species, and is sensitive to both variations of the most abundant species (i.e. the most printed authors) and of the rarest ones (the least printed authors).

-

The Hill-Simpson diversity index (Roswell et al.) is particularly suited if we are interested in differences in abundance of the most common species (here, the most frequently printed authors).

Figure 4 shows how these metrics evolve across decades.

After peaking in the second half of the 17th century, all measures start to decrease, the steepest decrease being visible for the Hill-Shannon index (accounting for all classes of authors), and the smoothest for Hill-Simpson (mostly focusing on the main authors). In order to test whether this trend can be observed above chance and independently of the amount of classical editions per decade, we proceed to test the robustness and statistical significance of the results with a sampling approach. First we verify whether the same trend is visible when randomly sampling in the same number of books over a certain span of time (Figure 5).[13]

The peak around 1670 is neatly visible also in this case. In order to test whether the second part of the 17th century is significantly “more diverse” than in the following period, we proceed with further verification, by using a permutation test.

For every period of 40 years, we count the number of books published and the number of distinct authors. We then sample randomly across all time periods the same number of books, and verify whether the number of distinct authors in the various samples is significantly higher or lower than in the time period examined[14]. Figure 6 indicates for every time period the p-value of the test of whether the period is unusually rich (positive values) or unusually poor in terms of distinct authors (negative values). The peak of the 1670–1709 period indicates the significance of the value[15], while the rest of the 18th century turns out to have a significantly low number of distinct authors. This confirms that we observe a sharp contrast between the second part of the 17th century and the 18th century and that we might be spotting the phenomenon of canonization.

These different metrics naturally lead to the conclusion of a reduction of the diversity of authors. To further investigate this hypothesis, we focus on the list of 20 most frequent authors in the total dataset[16]. Taken together, they are published in 3905 records, whereas the remaining authors (290) are published in 3244 records. Both sets of editions increase linearly over time, but as is shown in Figure 7, the rate of change is higher for the frequent authors than for the others[17].

As a result, in the course of the 18th century, the overall weight of the editions of the “top authors” steadily increases, to the expense of the remaining authors. Figure 8 shows the relative impact on the total number of classical editions of the two groups per decade. After 1650 we can clearly see a steady growth of the top-20 authors, and, consequently, a decrease of the other group.

In order to better explore how the two groups evolve in the 18th century in comparison with the 17th century, we check whether the growth of publications (predicted by the 17th century — in red) mirrors the (actual — in blue) growth of the publications of top-20 authors of the 17th and 18th century, and of non top-20 authors (Figure 9). To this scope we trained two negative binomial regression models[18]: one is trained on the 20 most frequent authors of the 17th century, and predicts how they are published in the 18th century; the other is trained on 17th century less-known authors and predicts how they are published in the 18th century[19]. Both models take as predictors the publication year and the number of “non-classical” publications per year (in order to better account for the fluctuations in publication frequency).

When used for predicting 18th century evolution, the two models visibly behave differently. The most popular authors in the eighteenth century had their works printed about as much as we would expect based on the seventeenth century. However, for the other, less well-known authors, it is a different story. Their works were printed much less than we would have predicted based on the seventeenth century. There clearly has been a shift over time, and the most popular authors are taking up more and more space in the world of classical literature, while the lesser-known authors are getting less attention. Two metrics confirm this difference: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), which is the average absolute difference between what we expected and what actually happened, and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), which tells us how much the predicted values differ from the actual values. For the popular authors, the MAE and RMSE are smaller than for less-known authors (10.2 and 12.9, vs 23.9 and 27.5)[20]. Our 18th century predictions based on the seventeenth century are closer to reality for well-known authors, and further off for less-known ones. The less-known authors are clearly not getting as much attention in the eighteenth century compared to what we might have thought based on the previous century.

3.3. A change in taste in Early Modern England

The classical authors and works printed in Britain naturally vary over time. A more granular examination of these fluctuations offers a more nuanced understanding of how the dissemination of classical literature evolved.

This analysis is based on ESTC data, split up in the periods 1470s–1690s (EEBO) and 1690s–1790s (ECCO). Given that we observe a drop in diversity in the 18th century, we first focus on the two sets of authors that were printed only in one of the two time periods. For the first period, we find 258 authors published in a total of 2337 books, while in the later group there are 197 different authors in a total of 3923 books. Of the 258 authors published up to the end of the 17th century, 113 are not published in the following century. 52 authors have been published only in the 18th century, however, and not previously. Table 3 and Table 4 list the most frequent authors exclusively published in each of the two periods.

The two tables show a very clear trend: late-antique authors (both Greek and Latin) lose weight in the circulation of Classics, whereas archaic Greek lyric authors such as Sappho, Alcaeus and Tyrtaeus, appear ex novo in the 18th century. The printing of the Byzantine encyclopaedia Suida indicates a renewed interest in the 18th century in Ancient Greek culture[21]. The list of authors exclusively published in either of the two sets confirms these trends: of the works of authors published exclusively in the 17th century EEBO span, Christian ones account for 109 titles, while ‘non-Christian’ ones number 223 (a 33%-77% ratio); in contrast, in the 18th-century ECCO span, there are only 23 Christian works versus 128 non-Christian ones, a ratio of 15%–85%. The Reformation and Restoration of the 16th and 17th certainly play a major role in explaining this phenomenon[22].

Changes can be observed also when looking at the “most important authors”. Table 5 lists the 10 “most published authors” for both periods, with the count of ESTC IDs, while Figure 10 shows the comparison of the relative number of prints in the two periods of the same authors. Some authors grow in (relative) importance over time (e.g. Horace[23], Homer[24], and Aristotle[25]), whereas others appear to become less central in the printed production of the 18th century (Plutarch[26], Augustine[27] and Seneca[28]). Conversely, Terence and (the Latin version of) Aesop are relatively stable authors in the two lists: they were key authors (alongside with the Dicta Catonis) in the English education in grammar schools (Verbeke, “Cato in England”: 139, Baldwin; Foster). Overall, the table predominantly features authors that were taught in grammar schools and universities (Mack), which suggests the large impact of education materials in the total publication output. To have a better overview of the authors whose importance changes the most, Table 6 displays the authors who gain and lose relative importance more strongly between the first and second period[29].

In order to have a systematical comparison of the two rankings, we use the Rank Biased Overlap (RBO, Webber et al.) metric, which assesses the distance between two rankings that do not necessarily contain the same authors, and where different weights can be assigned to the difference/similarity of the top positions in the ranking, by changing the hyperparameter “p”. A score of 1 indicates that the two rankings are identical, a score of 0 that the two rankings are constituted of entirely different items. In this case, most of the actors will be identical, but the score will reflect differences in the order. Here, we set p to 0.9, 0.99, 0.995 so that the first 10, 100 and 190 ranks respectively are assigned approximately 85% to 86% of the weight of the evaluation. The results (0.59, 0.58, 0.41) show that the two rankings display relevant differences, especially when the set of “lower ranked” authors is taken into account[30].

These observations confirm that the loss in diversity coincides with a shift in interests. Significant differences can be observed among the most prominent authors (namely, the increased importance of Homer, Aristotle, and Horace). However, the most substantial impact of this transformation appears to affect the authors who are least printed, many of whom cease to be reprinted as new interests emerge (e.g., Greek archaic poetry).

4. Differences in Ancient Greek and Latin publications

In this section, we focus on the linguistic dimension of the circulation of Classics. We combine ESTC, EEBO and ECCO metadata to distinguish the trends of publication for Latin and Ancient Greek authors respectively, and to identify the languages in which they were published. First, we compare the printing of editions of Ancient Greek and Latin authors with the number of editions in the three most attested languages for this set, namely English, Latin and Ancient Greek (Section 4.1). With section 4.2, we delve into the inclusion of these texts and languages in the two catalogs (EEBO-TCP and ECCO-TCP) which, among other things, are the starting point for studying the circulation of Classics based on the full text of the publications. Section 4.3 and 4.4 investigate the distribution of languages for classical editions in EEBO and ECCO respectively.

4.1. Ancient Greek and Latin authors: comparing trends

When studying the circulation of Latin and Ancient Greek texts in Early Modern Britain, the language aspect is a central question. First of all, the availability of large datasets allows us to investigate the relative importance of literature in Ancient Greek and Latin, and how the interest for these two faces of the classical world evolved over time. Section 3 already pointed to a renewed interest in Greek literature in the 18th century. To confirm this impression, we have manually divided the ancient authors into those writing in Ancient Greek and Latin respectively. The balance between Latin and Greek authors evolves over the years. While in the first stages of English printing, Latin authors predominate, in the second half of the 18th century the two values are balanced (Figure 11)[31].

Moreover, the language of publication of classical works provides an overview of the impact of translation in the access to classical texts. The importance of translation (and of import) in the evolution of printing in Britain is well known (Hosington; Ellis et al, in particular volumes 1–3)[32], as well as the complexity of the process, often based on intermediary translations and not relying on the original languages of the works. This applies to Classics as well (Hosington 11). Previous studies highlight the complexity of the cultural operations involving translation (see Section 1.1 and Verbeke, “Cato in England”; Verbeke, “Types of Bilingual Presentation”; Schurink): for this reason here we do not focus on the process of translation per se, but simply on the broad picture emerging from the language-information attached to the metadata as this can be mined from the textual snippets. In general, the translation of Classics has been recognized as a fundamental aspect not only for the access to the ancient culture, but also for the shaping of the Early Modern literary production in England (Gillespie 65–67).

The version of the ESTC catalogue currently exploited features the field ‘language primary’, identifying one language per record. The most represented languages in classical editions up to the last decade of the 18th century are shown in Table 7.

The two predominant languages are English and Latin, followed at a distance by Ancient Greek[33]. The evolution over time of the three main languages is shown in Figure 12, and turns out to be rather stable. The “revival” of Ancient Greek authors does not result in a stable increase of the circulation of Ancient Greek texts. However, the field “primary language” does not account for the circulation of publications in multiple languages. For instance, for the ESTC ID “R231767” “Pindarou Olympia, Nemea, Pythia, Isthmia Pandari Olympia, Nemea, Pythia, Isthmia : una cum Latina omnium versione carmine lyrico /per Nicolaum Sudorium” (ESTC ID “R231767”), only the language Ancient Greek (or better, erroneously “Modern Greek”) is recorded, whereas it is clear from the title that the work presents a Latin translation together with the original text.

4.2. Representation of classical editions per language in EEBO, EEBO-TCP and ECCO

In view of a future study of the circulation of Classics based on the full text recorded in EEBO-TCP and ECCO-TCP (cf. Conclusions and Future Work), we assess how the classical editions are represented in the two databases based on the language, and we break down the counts of languages of publication on the basis of the language of origin (i.e. Ancient Greek or Latin). This elucidates what type of material is available for the study of the full-text transmission.

In Section 2, we have already highlighted that the inclusion of Classics in the full text catalogs presents highly different patterns: high representation in EEBO, very low in EEBO-TCP and only partial in ECCO. It is natural to wonder whether the language of publication (e.g.. English translations of classical works vs non English editions) or the script of editions (Ancient Greek alphabet vs Latin scripts) influences the selection. This is highly relevant, especially in view of the identification of passages of classical editions in the rest of the catalogues.[34] In the following paragraphs, we indicate the languages appearing in the published book as “language(s) of publication” or “language(s) of edition”, while the expression “original language” refers to the language in which the works were written in Antiquity (for this study, either Ancient Greek or Latin).

Ongoing studies highlight that the coverage of EEBO and EEBO-TCP varies on the basis of the language of publication of works: while English, Scots and Welsh works are well-represented in both, EEBO-TCP rarely features more than 10% of the works in other languages, while EEBO’s coverage ranges from 70% to 80% (Mäkelä et al.). These numbers are confirmed for the specific subset of classical editions, as it can be seen in Table 8.

Although EEBO’s coverage of Classics is quite high (above 80% for all languages), EEBO-TCP’s significantly declines for editions in Latin and Ancient Greek: it is safe to conclude that the transcription of the full text was carried out almost exclusively for classical editions featuring an English translation. The inclusion in the ECCO catalogue (and hence in ECCO-TCP) only partially differs from EEBO. Table 9 demonstrates that the common trait between ECCO(-TCP) and EEBO-TCP is given by the complete exclusion of Ancient Greek editions, while, contrarily to EEBO-TCP, Latin editions are well-represented in ECCO(-TCP). It is important to underline that at this point we are only discussing the language of edition, and not the original language. In addition, since we are relying on the ‘primary language’ metadata field only, the multilingual dimension of the texts is not captured. Both points are expanded in the next two paragraphs.

In the following paragraphs, we analyze the situation of the languages of publication in EEBO and ECCO in relation to the original language of the works. The exploited version of the EEBO catalogue contains only one language of edition[35], and we can infer the language of origin thanks to the mapping of the authors (Ancient Greek authors are assigned as language of origin Ancient Greek, and Latin authors Latin). For ECCO, we manually annotated both the original language of the work and all the languages of publications.

4.3. Latin and Ancient Greek authors in EEBO

Figure 13 shows two columns with the amount of Ancient Greek (grc) and Latin (lat) authors published in EEBO, each specifying the distribution of the languages of publication.

Publications of Latin authors outnumber those for Ancient Greek ones (1235 vs 875, i.e. 59% vs 41%). Ancient Greek works are mostly published in English or Latin (resp. 543 and 222), with only 106 works published in the original language (i.e. 12% of the publications of Ancient Greek authors). As the ECCO data will show, it is likely that more Ancient Greek texts are present, but coupled with Latin or English translations. These simply do not surface in an annotation system where only a single language is detected. A simple search for the string “Grae*” in the title of the editions whose author is labeled as Ancient Greek, but whose language of edition is not Ancient Greek, identifies a number of bilingual editions that are not visible through the metadata. For instance, the EEBO edition ‘Platonis De rebus divinis dialogi selecti Græce & Latine in commodas sectiones dispertiti : annexo ipsarum indice.’ (ESTC ID R10294) is a bilingual edition (Latin-Ancient Greek) of an Ancient Greek work, with ‘Latin’ as metadata language. Latin is better represented as language of edition of Latin authors: of the 1235 Latin works, 511 (41%) are published in the original language, while 58% in English.

Table 10 provides a detailed examination of the EEBO-TCP situation.

The balance between Latin and Ancient Greek authors in EEBO-TCP is rather similar to EEBO: 336 vs 241 (60% vs 40%). From this point of view, the coverage of the two sets is comparable. In terms of language, however, we are left almost exclusively with English translations, and a very small set (13) of Latin original editions, or of Latin editions of Ancient Greek works (2). Hence, using EEBO-TCP for exploiting the full text of the editions would yield a balanced representation of Ancient Greek and Latin authors, but would provide a very bias account of their circulation from a linguistic point of view.

4.4. Latin and Ancient Greek works in ECCO

In this section, instead of relying on the ‘primary language’ found in the metadata, we rely on the manual annotation of students of Classics. The students only annotated ECCO data (and not the full ESTC) for feasibility reasons and as a propedeutic exercise to the full text analysis of ECCO-TCP. For each text, both the original language and all the language(s) of publication are indicated based on the title and on information available online. In the ECCO database, the distribution of original languages is similar to the one in EEBO, even though Greek authors gain some prominence, consistent with the trends displayed in Figure 11: 1890 works of Latin Authors vs 1477 works of Ancient Greek ones (56% vs 43%). The comparison with EEBO, however, only partially holds, since we have seen that, while EEBO includes metadata of editions published in Ancient Greek, ECCO excludes them[36]. Hence, the real figure for the 18th century should in all likelihood be more in favor of Ancient Greek authors. The quality of the human annotation allows a more precise analysis of the way in which editions of Ancient Greek and Latin authors circulated. Table 11 shows how many editions (ESTC IDs) feature 1, 2, 3, … languages, split according to their original language.

Most of the publications are thus monolingual (1082 Latin texts, and 682 Ancient Greek texts). When more than one language is found, the situation can vary significantly: in some cases, we find bilingual publications in the form of the original text accompanied by a translation. For instance, the ESTC ID T67047 “Pub. Virgilii Maronis Georgicorum libri quatuor. The Georgics of Virgil, with an English translation and notes. Illustrated with copper plates. By John Martyn, F. R. S. Professor of Botany in the University of Cambridge” contains a Latin edition of Virgil with an English translation.

In other cases, the work is essentially monolingual but some specific part of the text is published in a different language. As an example, the ESTC ID T132865 “The selected dialogues of Lucian. To which is added, a new literal translation in Latin, with notes in English. By Edward Murray, M.A. [Two lines of quotations in Latin]” contains a Latin translation of Lucian (work originally written in Ancient Greek), with notes in English.

Since quantifying these nuances is problematic, we focus on the monolingual editions, representing the vast majority of cases[37]. Figure 14 compares the language of edition for monolingual editions of Ancient Greek and Latin works.

Monolingual publications of Latin authors outnumber those for Ancient Greek ones (1079 vs 682, i.e. 61% vs 39%). It is important to recall again that none of the 254 Ancient Greek works present in ESTC for this period is included in ECCO, which of course heavily undermines the reliability of this statistic. Within the ECCO selection, hence, Ancient Greek works are mostly published in English or Latin (resp. 612 and 43). On the contrary, the circulation of Latin among the monolingual publications of Latin authors is clearly visible: of the 1079 Latin works, 594 (55%) are published in the original language, while 43% in English. Ancient Greek is frequently attested, however, in bilingual editions: out of the 239 bilingual editions of Ancient Greek authors, 217 feature Ancient Greek as one of the languages, either combined with Latin (212 cases) or with English (5 cases). The titles confirm that in most cases the edition of the Ancient Greek text is coupled with its Latin (and in a few cases, English) translation (on the Renaissance period, see Binns).

The main conclusion of the analyses of languages in ESTC, EEBO(-TCP) and ECCO is that the increase in editions of works of Ancient Greek authors during the 18th century, does not translate in a clear revival of editions in the original language, whose number remains rather stable. However, we cannot account for the evolution of printing of Ancient Greek editions with their translation, due to the fact that the ESTC metadata set used only includes the primary language. Moreover, in terms of representations in the catalogues with full-text transcription, Ancient Greek works are substantially excluded, while the presence of Ancient Greek and Latin authors remains balanced.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

The statistical analysis conducted in this study provides valuable insights into the circulation of Classics in Early Modern Britain. It reveals the dynamic and complex process involved in establishing a ‘canon’ of Classical authors. While the overall number of printed Classical authors increases, their influence on the broader printed production of Modern Britain consistently diminishes over time. Moreover, a notable narrowing of the pool of authors receiving attention becomes evident, with lesser-known authors experiencing reduced printing in the 18th century, contrary to 17th-century trends. A shifting focus of interest is also apparent, with religious authors losing prominence and Ancient Greek authors, particularly those from the early period, gaining increased attention, eventually rivalling the distribution of Latin authors.

From a linguistic perspective, an intriguing pattern emerges, indicating an opposing trajectory for the two languages under scrutiny. Monolingual Greek editions of Ancient Greek authors noticeably dwindled in the 18th century, while Latin retained a substantial role in the dissemination of Latin authors. The diachronic analysis is made difficult, however, by the different annotation processes of the EEBO and ECCO catalogues. It is nonetheless worth mentioning that Latin translations associated with the original Ancient Greek texts widely circulated in the 18th century. This observation highlights the significant role played by English translations in the dissemination of Classics, reaffirming the unique character of the English press, where vernacularization seemed to take root particularly early, and the impact of translations was notably pronounced.

From a methodological perspective, using metadata is a practical way to examine large-scale phenomena and to study how the works of various authors, both classical and modern, were disseminated. A valuable future endeavor would be to contrast the chronological dynamics uncovered in this study for the British Isles with canonization processes in other regions, such as German- or French-speaking areas. Such research efforts would benefit greatly from the existence of an author-based retrieval system equipped with unique identifiers. Generalizing over several countries would allow to spot more complex patterns bridging the political and historical dimension with the cultural one, contributing to the field of cultural evolution (see for instance Henrich).

In order to get a better picture of the circulation both of specific authors and of languages, we are undertaking a two-fold approach, that we wish to develop in the future. On the one hand, we are exploiting the available transcriptions of the EEBO-TCP and ECCO datasets, to detect passages of classical editions that are reused in non-classical editions. This allows to map what authors were quoted the most, which complements the information about the amount of printed editions for each author. However, this endeavor comes with several challenges[38], namely the noise of the detection, and the difficulty of distinguishing between one author quoting another one and two authors quoting a common source, e.g. the Bible. A second approach, consists in detecting the language of the reused passages, and comparing them to the surrounding snippets of texts. This results in the identification of, for instance, Latin passages in an English context, and refines the information provided by metadata on the language of editions of the texts. For instance, focussing on text-reuse, we are currently working to single out cases of reuse of common sources, in particular to eliminate biblical references from the matching pairs. To efficiently produce statistics on the reused passages, we will cluster similar texts to identify the reused snippets. In addition, it would be relevant to run the language detection not only on the reused snippets, but also on the whole body of source texts. This would allow us to be more precise about the mixture of Latin, English and other languages, and enrich the metadata with these results.

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KUDWJJ

Peer reviewer: Glenn Roe (Sorbonne University), Mike Kestemont (University of Antwerp)

_identified_as_classical_editions_published_per_decade.png)

_vs_number_of_unique_classical_authors_published_(.png)

_attributed_to_frequent_classical_authors_(sky_blue)_and_thei.png)

_to_the_ot.png)

_vs_the_rest_of_the_auth.png)

_authored_by_the_top_10_most_prolific_authors__either_fr.png)

_attributed_to_latin_authors_(in_orange)_vs_number_of_estc_i.png)

_and_latin_(lat)_original_works_and_their_languages_of_publi.png)

_identified_as_classical_editions_published_per_decade.png)

_vs_number_of_unique_classical_authors_published_(.png)

_attributed_to_frequent_classical_authors_(sky_blue)_and_thei.png)

_to_the_ot.png)

_vs_the_rest_of_the_auth.png)

_authored_by_the_top_10_most_prolific_authors__either_fr.png)

_attributed_to_latin_authors_(in_orange)_vs_number_of_estc_i.png)

_and_latin_(lat)_original_works_and_their_languages_of_publi.png)