1. Introduction[1]

Aim of the study

Jewish German filmmakers went into exile in 1933 or a few years later because they were dismissed or not offered further employment in the German film industry. Anti-Semitic attitudes determined many areas of German society even before the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. The exclusion from the Reich Film Chamber in 1933 sealed the impossibility of finding work; it was de facto a withdrawal of the work permit, often accompanied by further threats to life.

By being forced out, at least indirectly, and often fleeing Germany unprepared, exiled filmmakers brought great benefits to other film industries. Hans Kafka summarizes this benefit in an article (Kafka 2) in which he writes about Hollywood’s gain from the new influx of talent. A list of artists who gained a foothold in Hollywood, including names still famous today, and the list of Oscars seal his argument.

“That is what Hollywood did for the immigration. On the other side of the balance is an equally impressive number of achievements. 1937 was the triumphal year when the Central European immigration cashed in forty percent of the academy awards: Luise Rainer, for acting in Good Earth, Joseph Schildkraut, for acting in The Life of Emile Zola, Heinz Herald and Geza Herczeg, for writing Zola, Carl Freund for photographing Good Earth. “Oscars” of other years went to George Froeschel, for writing Mrs. Miniver, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, for the score to Robin Hood, Luise Rainer for acting in The Great Ziegfeld, Max Steiner for composing The Informer, and to many others.”

The emphasis on productivity and success stories seemed necessary to Kafka in 1944 to portray European immigrants as beneficial to American society. The overall pressing zeitgeist emphasizes work ethic and awards over the story of flight and expulsion.

It should be noted at the outset that the flight and the new beginning in another country took place under the most difficult conditions. The friends and family members who had to be left behind and most of whom were murdered do not appear in data analyses of film professionals and cooperations (Klages and Schneider 237). Nor can the many people whose escape and other lives were not recorded by the data collection be identified further. Consequently, the aim of this study with digital methods is to highlight the film work of the exiled persons as an exceptional achievement despite personal stories of expulsion and to make this fact more visible in charts and numbers.

Basic information on the data set of the Straschek estate

The analog estate of over 125 archive boxes and approximately 3,357 personal files of film exiles with bio-bibliographical data and correspondence of Günter Peter Straschek came in 2014 to the Deutsche Exilarchiv 1933-1945 in Frankfurt am Main. The personal files of Günter Peter Straschek - compiled over almost thirty years - usually contain a cover sheet. This sheet, often closely typed, summarizes various information in the file. It is structured along the lines of names, pseudonyms, dates of birth and death, spouses, countries of transit, professions, and sometimes information about personal interviews, the archives Straschek consulted, and a brief biography of the film work. These cover sheets form the data basis for the presented research.

For Günter Peter Straschek, the German film exile includes all persons involved in the German film industry and film culture between 1920 and 1933 who went into exile before 1945. His definition also includes film critics and employees in the field of film distribution and screening. Straschek decided whom to have in his collection based on his research between 1976 and 2009 (Klages and Schneider 222–27). His list is not a complete list of exiled filmmakers. Nor does Straschek’s list of names include the numerous film and cultural workers murdered by the Nazis.

Nevertheless, the Straschek estate contains a wealth of data, e.g. on the escape routes and various countries of exile, which emerges from interviews conducted and correspondence. In other reference works, many of the people contacted by Straschek cannot be found, so his collection is sometimes the only reference to this person.

Assessing the data presented is necessary to show that more information on exiles is needed on all online resources connected to the project, such as GND, Wikidata, and IMDb.

Straschek’s collection

Straschek used the contact data from the WDR broadcast series “Filmemigration aus Nazideutschland” 1975 to send extensive questionnaires for his research project systematically. The questionnaire asked for life data, information on family members, curriculum vitae, escape history, and occupation in exile. Detailed questions also addressed work permits abroad, union membership, artists’ agencies, difficulties in the context of House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings, and experience with aid organizations. These details were only rudimentarily recorded in the reference works (Strauss et al.). The recollections and reports in the Straschek files make the working and living conditions in exile vivid. After all, exile fundamentally differs from moving abroad as part of career planning. These details illustrate the conditions under which the numerous films were made, evaluated under 2. and 3.

Verification of the data and challenges

Since the Straschek estate was handed over to the Exile Archive of the German National Library, the persons in the personal files have also been recorded as individuals using the GND, the standards file. Thus, a digital record of the personal data of the collection is now available. The exiles often have multiple pseudonyms, so verifying an individual presents challenges. Before a person is recorded for the GND, the person in question is confirmed by two sources. For this purpose, various encyclopedias and reference works are listed for the GND. In many cases, the Straschek estate was now considered one of these sources, as he had also collected exiled persons’ birth and death certificates in his files when available. These analog sources were considered when the personal data were included in the GND and, in some cases, corrected if they contained incorrect information or were unavailable.

The traces have disappeared; how do we show the gaps?

The collection’s research status is in 2009 when Straschek died, and many files still need to be revised or updated with new information and findings.

The files show that the data must be completed. Furthermore, who today can still research a cinema technician who once lived in Vienna, had to give up his residence after 1938, and whose only entry in the Vienna City and Provincial Archives is “deregistered for Madrid, Spain”? There is only one name and one outdated address. The traces have been covered. The trail of the rupture can be found in these gaps.

The gaps in the data sets should be presented at the beginning of the investigation to relate the results to the missing data and the many people who remain without references. The missing data shows that many more people, including film industry employees in the broad sense, went into exile than can be determined.

“Computational methods neither replace interpretation and hermeneutics nor do they melt with them. No number, no datum interprets itself. As part of the Humanities, the Digital Humanities have to deal critically with the scope and limits of data-driven methods.” (Krämer)

For this article, the exiles who were still children (born 1921 and younger) are not included in the population of the tables. Those persons who were given a file by Straschek but were not counted as part of the film exile because they remained in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945 and sometimes continued to work for the film industry were also sorted out.

There are 3,357 personal files in the Straschek estate. The higher number of persons in the GND with 3,615 can be explained by the fact that even more names appear in the single files, but these names do not have a file in the Staschek estate. However, these persons without a file still received a GND number for an existing person. For example, the cameraman Willy Goldberger has a file with Straschek, but his brother Isidoro Goldberger does not; he is listed under his brother’s file. Nevertheless, he received a GND number, which is how the different numbers of the estate and the GND come about.

Wikidata contains 2,471 of these persons but has more vital records for this number of persons; this shows that if Wikidata has a person entered with his or her ID, that person also mostly has entries in the vital records. IMDb, on the other hand, lists 1,931 people from the Straschek film exiles, again with fewer vital records on this platform since this database focuses on filmographic data rather than vital records. However, these are sometimes incomplete and subject to the platform’s rules.

The total person count combines the different sources on the names and emphasizes the importance of cross-reading the database when working with vital records in a digital project.

The comparison of biographical data in the various online resources reveals that different data sets can produce different results and statements about people in the film exile. The data situation should be reflected and put into perspective. In the Straschek files, we are partially missing over eight hundred entries on years and places of death, and even with the years and locations of birth, there are still over four hundred people listed without this data. Wikidata has only 64% of the persons in the aggregated holdings (100% equals 3,870 persons). On IMDb, only 1,931 people have film credits and thus represent 50% of the aggregated stock of 3,870 persons; this will be important later for the data analyzed in 2 and 3. The proportion of film collaborations involving exiles was even higher than it became traceable via online platforms.

2. A devastating loss

Productivity

“The quantifying, computational methods of the Digital Humanities operate like computer-generated microscopes and telescopes into the cultural heritage, ongoing cultural practices, and even the culturally unconscious.” (Krämer)

Hans Kafka (see above) could have extended his list of persons even further to include the entire build-up issue presented above, as the number of film credits per exile reveals an astonishing productivity of 13,866 film credits in the study period 1930 to 1950. These numbers do not include the very productive years from 1950 to 1980 (a total of film credits over the period 1900 to 1997 yields 46,385 film credits by persons with an IMDb ID (1,931 persons), including multiple film credits for one film when, for example, two activities were credited to one person). Individuals who worked on films but were removed from credits for political, financial, or union reasons are not included in this list. However, they are counted if listed as “uncredited” on IMDb.

The numbers do not give any information about the respective CVs, e.g. the multiple changes of exile countries.[2] They only refer to the collaboration on films despite flight and expulsion from 1933 to 1945.

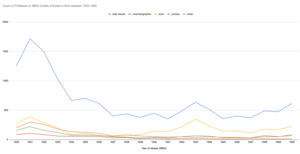

This table lists the exiles’ IMDb credits per year of release from 1930 to 1950.

The number of participants in the film industry after 1933 dropped from 1,033 film credits in 1933 to 667 film credits in 1934. The result speaks to the effects of exile and flight on the possibility of successfully practicing the profession as it was still in the early 1930s. During the war years, the numbers decreased even further to 380 credits in 1939 and 352 credits in 1941. Moreover, even up to 1950, this number of participants in film projects via film credits has not recovered significantly.

Global search for employment: Countries of production

The table supports the thesis of the worldwide participation of exiles from Germany in the international film industry after 1933 and the exodus from Germany.

The number of professional activities of the exiles in the films from 1930-1950 was listed and analyzed in Table 3. Table 4 shows the number of exiles in the films from 1930-1950. Both Figures 1 and 2 indicate the rupture. In 1932, the production country Germany (without co-productions) still employed 1,112 film credits, which shrank to 24 film credits in 1939 for exiles. In the USA (also without co-productions), on the other hand, the situation is reversed; there, only 27 film credits for émigrés can be recorded for the production country USA in 1932 - in 1939, on the other hand, there are already 182 and one year later in 1940 we count 275 film credits.

3. Collaboration on the flight: Interconnectedness

The well-trained émigrés were able to stay in their professions. The camerapersons of the film exile found work everywhere, and their technical know-how was in demand - except the union of the country of exile, as in the USA, would not let them join (Asper 351). The cameraman Adolf Schlasy is an example of someone who quickly finds work abroad. He worked in Austria, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Argentina (see Figures 3 and 4 for Adolf Schlasy).

The graph (Figure 3) shows only the film collaborations with other émigrés, but Adolf Schlasy also worked on other films. The graph reveals information in an abstract form. In laying open the data sources and gaps (see above 1. Introduction), meaning can be extracted only by adding historical context, and the investigation can progress. Compared with other personal graphs for the same period (Figure 4), this meaning can be set into relation.

Frank Planer worked in a seemingly denser network of exiles (Figure 4). However, his connections to other émigrés were much more vital for his German films in the 1930s. These are visualized around the mauve knot “Germany” in the upper right part of the graph, showing his German productions and émigrés involved.

The instrument of a graph visualization of a given data set can show the interconnectedness through film projects in a set period. It is always only the beginning of a historical investigation, a tool to find a close working relationship for that time. It cannot be the end of a set research question, as the graph leads to more rather than fewer questions. In the different personal graphs, there is an exploration of numerous collaborations possible.

Support for artists on the run also came, for example, from already well-connected individuals such as the film producer and film agent Paul Kohner and the Kohner Agency in Hollywood. If they had worked together successfully, cinematographers, scriptwriters, producers, actors, and other film personnel followed producers or colleagues in a film project.

The following tables should examine this collaboration. Table 5 lists the 1,656 individuals who can show association with another émigré from the Straschek list on a film project. This table includes all films with exile participation from 1900 to 1997, so collaborations from the 1920s or the 1960s were also counted.

Table 5 shows the names of the exiles (column B) and their total number of films (column C), as well as the number of films made with other exiles (column D), the number of jointly realized projects with people from the film exile (column E), their gender (column F) and their activities, arranged alphabetically according to the sources Straschek Nachlass, GND, and IMDb (column G).

The number of realized projects among émigrés clarifies some interesting background on the production history of films. Hans J. Salter stands out as a composer of film music with 573 entries, but among them are many entries for stock music, which are nevertheless counted here as “uncredited.” The observation that film musicians, composers, and conductors got a good start in Hollywood also emerges from the research literature (Horak; Asper; Weniger). This table reaffirms the findings of said film historians. When actors stood before the camera, they had to know the new country’s language or lost engagements and roles. Film music was ahead of the actors in that music is a universal language.

It turns out that actor Jack Mylong-Münz collaborated with other émigrés 447 times in 159 film projects, the highest frequency among exiles. It is hardly surprising after a closer look at his filmography because he had also worked for the German film industry since the early 1920s. Many joint film projects date back to the 1920s and early 1930s before the exile. He also starred in many US Anti-Nazi films.

Thus, the collegial relationships from the 1920s that developed during film work on German productions or co-productions provided a foundation for later working relationships in exile.

4. Conclusion

Film émigrés rendered an excellent service for their countries of exile. Digital methods helped to uncover the agency even further. In Digital Humanities research, digital sources must be reviewed across multiple platforms.

Why are the film exiles so interesting for transnational and digital film history?

In a very short time, they had to flee the German film industry and find a foothold in another one. Among them are the most prominent and productive representatives, such as Paul Abraham, with over sixty film credits, whose songs were the talk of the town, or Franz Planer, a very successful cinematographer, who later recorded the classic “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and shows over 160 film credits. They crossed many national borders, worked in many places, and they adapted to the circumstances. On the contemporary level, film émigrés bring forth transnational research and collaboration, as researchers from different countries are interested in their films, biographies, and activities for the very reason of moving to other film industries. Digital history does not occupy a singular position between the digital and the historical (Kemman). A continuous development exists, transcending national borders in research (Noordegraaf et al.) and cross-disciplinary engagement. Reading German film exile with digital methods allows to discover global interconnectedness within film history even further.

Funding

This article is based on the DFG-funded project “Mapping German Film Migration 1930-1950. Eine datengraphbasierte Perspektive auf die Filmemigration aus NS-Deutschland” (project no. 444817764).

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ILHFPM,

This article is based on the DFG-funded project “Mapping German Film Migration 1930-1950. Eine datengraphbasierte Perspektive auf die Filmemigration aus NS-Deutschland” (project no. 444817764). Horak, Hilchenbach and Asper’s pioneering film historical work lays the foundation for the research in this field.

Individual biographical details can be found either in the individual personal files of the Staschek estate or in the biographies and autobiographies of the exiles.

_limited_t.png)

_worked_with_other_exiles_on_film_projects_from_1930_to_1950.png)

_worked_with_other_exiles_on_film_projects_from_1930_to_1950.png)

_counts_of_collaboratio.png)

_limited_t.png)

_worked_with_other_exiles_on_film_projects_from_1930_to_1950.png)

_worked_with_other_exiles_on_film_projects_from_1930_to_1950.png)

_counts_of_collaboratio.png)