Introduction: A New Perspective on Early Cinema Readers

In issue no. 124 (13 December 1928) of Barcelona’s film magazine Popular Film, a periodical which would go on to become one of the most influential cinema magazines in 1930s Spain (Alberich et al. 455), a headlining article about Hollywood’s Latin lover Ramón Novarro began with the author’s rejection of such frivolous considerations as the actor’s physical beauty:

If I were eighteen years old, had long hair, short ideas and even shorter skirts, maybe the beauty of the famous Mexican actor would interest me. With my short hair, with the urgent need I have to shave every day, with the elephant-leg pants I wear and with the ideas that come to my mind, I couldn’t care less about the manly poise of Ramón Novarro. […] How does Ramón Novarro comb his hair? For me, to be honest, he can part his hair in the middle, I wouldn’t notice and it shouldn’t worry me in the slightest. But for you, most beautiful reader, things are different.[1] (Pego 3)

Using the grammatically feminine-marked form of ‘reader’/lector, Aurelio Pego, the article’s author, characterizes Novarro’s fan base, and by extension, the magazine’s readers, as an adolescent young woman of intellectual short-sightedness interested only in silly things like how movie stars do their hair. Whereas female fan behavior is belittled as gossip and a preoccupation with beauty and fashion, the author’s remarks gesture to the male counterpart as a movie fan disinterested in the personal lives of cinema’s movie stars or Hollywood gossip.

In reality, a systematic survey of popular Spanish film magazines reveals Spain’s early cinema fan base was composed of a strikingly large proportion of male readers.[2] In fact, in the years leading up to the introduction of sound film in 1929, male readers avidly read and persistently engaged with popular film magazines through two central modes of interactivity: fan mail and participation in reader contests, particularly the star-search photo contest. Through their inquiries to magazine editors and their expressive photographs, male readers exhibited attentiveness to the sorts of things that Pego attributed to a silly ‘screen-struck girl’—the personal lives of movie stars and where to write to them—and displayed hobbyist dispositions and creative effort as avid movie fans, knowledgeable about the style of movie stars. As the present study demonstrates, male readers from all over Spain, across geographical regions and social classes, were remarkably invested in celebrity consumer culture, revealing that they were not disinterested spectators of cinema but devoted cinema culture readers.

In the burgeoning body of research on the early movie fan,[3] studies of the cultural history of cinema have charted the progressive feminization of movie fandom in the silent period and have traced the rise of the archetype of the ‘screen-struck girl,’ a young female movie spectator overinvolved in her film enthusiasm and feverish in her longing for stardom. Yet few scholars have considered the male cinephile, though many have been careful to note that early movie fandom was never a distinctly female practice. Male movie fans of the silent film period have largely gone unaccounted for, under the assumption that they denigrated or had little interest in cinema culture (Fuller-Seeley 118). This rings true in the case of Spain, where “masculinist elitism” has traditionally defined the cultural and literary canon (Zubiaurre and Kurtz 108), aligning men with the nation’s high cultural repository and to the roles of intellectuals and literary or film critics only interested in aesthetic debates, and not as fans eager to participate in mass cultural celebrity consumer culture, for example.

To our knowledge, a sustained analysis of early male movie fans and their fan practices, in any national context, has been provided only by Courtney Andree (2014), in her consideration of the United States silent film era context. Pertaining to Spain, we have been unable to identify any case studies pertaining to men, either as film fans or, by extension, as consumers of popular film magazines in the silent period, or which offer any demographic data on early film magazine readership more generally. As film magazine readers were necessarily also film viewers, this lacuna in film audience research parallels digital approaches to the study of Hispanic new cinema histories, still underutilized, despite the growing body of digital humanities projects that have turned to computational methods to study, for example, the history of moviegoing, exhibition and distribution in New England during the 1920s (Klenotic 2011), the circulation of silent-era film periodicals (Hoyt 2014), and the ways online databases may shape the study of historical film cultures in the Netherlands (Noordegraaf et al. 2018).

This project contributes to an archeology of cinema fandom broadly, and fan culture in Spain specifically, by spotlighting male film fan readers during the silent film period. We take as a case study fan interactivity with Popular Film, during the magazine’s first three-year period, before the onset of sound cinema, and encompassing 175 issues. The term ‘cinema fandom’ is here understood as a social phenomenon encompassing participatory reception practices—of both creative and critical dimensions—characterized by a love for the movies among mainstream audiences (as opposed to elite, intellectual circles). We characterize Popular Film as a ‘fan magazine’ in that it elicited and received interaction and participation from readers who identified themselves as, or the magazine itself identified as, film ‘fans’—variously referred to in Spain as “admirers,” “aficionados,” or “lovers of cinema.”

To complement hundreds of hours of close reading, this project turns to digital methods—text mining, topic modeling, data processing and data visualization, GIS mapping, and network analysis. In so doing, we reflect on and highlight the need for a ‘toggling’ mixed methods interpretive framework using close and distant reading when conducting digital periodical research, where particular challenges are posed when working with periodicals in a non-anglophone written language, and when there are few studies to rely on to help guide and contextualize the patterns picked up through strictly macro methods. Ultimately, close reading that is augmented by computational evidence allows us to amplify our understanding of Spain’s cinema audiences and magazine readers and enables us to “[…] ground quantitative generalizations in concrete particulars of micro-historical case studies of local situations” (Maltby and Stokes 21).

Turning to an investigation of the two central participatory exercises of the fan magazine Popular Film—that is, the fan mail section and the reader star-search photo contest, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to unearth demographic data on readers of Spanish film magazines, and the second to provide a sustained consideration of early male film fans (in Spain, and in any national context).[4] The scarcity of demographic data on early film audience composition in Spain (i.e. sex or age) renders fan mail and published fan photos invaluable archives towards reconstructing profiles of magazine readerships. Thus, as a sociologically-oriented survey of reader composition, this project provides sorely needed data to reconstruct a profile of early film audiences, a line of study “notoriously difficult to comprehend” in the early cinema period (Biltereyst 228). Building on recent efforts turning to computational methods to study magazines and kiosk literature of the Spanish Silver Age (Romero López and Zamostny 2022), this project is a first step towards broader application of digital humanities methods to the study of cinema print culture in Spain.[5]

Doing Digital Periodical Research in Spanish: Thinking With Digital Methods & ‘Toggling’ Between Distant and Close Reading

In this section we reflect on the challenges of conducting digital periodical research and the affordances of a mixed macro-micro approach entailing distant reading and traditional textual studies of close reading. We adopt the view that a hybrid methodology of distant and traditional close reading enables an augmented reading that is necessary for any kind of computational approach to historical periodical research. As asserted by Ryan Cordell,

[…] the best digital periodicals scholarship moves between scales and media, demonstrating how observations at the macro level, drawn from digitized corpora, align—or do not—with observations at the micro level, drawn from archival texts. Such work pairs the unique capacities of the computer with the interpretive talents of the human reader […]. (Cordell et al. 5)

In a similar vein, scholars in wide-ranging, textual-based digital humanities projects have increasingly promoted combined research methods, highlighting the productivity of integrating both scales of analysis (Liu 2011; Howell et al. 2014). In particular, we borrow Hoyt et al.’s computational metaphor of ‘toggling’ (26) between different modes of analysis. Ultimately, we suggest that it is imperative to think with, and not be substituted by, digital methods, which must be founded, as well as tested, on close reading.

The increasing digital availability in Spain of volumes of cinema-related print forms such as magazines has invited a new line of computationally-driven research on a grand scale. For this project, we relied on the digital repository of Catalonia’s Film Archive (Filmoteca de Catalunya), a large collection of material growing since 2013 that, in addition to film magazines, includes musical scores, personal legacies, film novels, and posters. As new material continues to be added, in 2019 a new version of the archive’s open-access digital collection developed which allowed for simpler navigation and additional content. Supplementing this source for the current project was the City Council of Madrid’s Digital Library memoriademadrid (Biblioteca Digital memoriademadrid) and the Digital Periodical and Newspaper Library of the National Library of Spain (Hemeroteca Digital de la Biblioteca Nacional de España).

The complexity and diversity of periodical formats is a methodical challenge for digital research (Fyfe and Ge 2). Such print publications comprise text alongside images, varied spacing and fonting styles (size, color, and typeface such as bolding or italics), intricate page bordering, advertisements, chunks of small texts, and content arranged in different layouts through columns, slanted, or circular divisions on the page. It is often overlooked that with periodicals there is also the frequent inclusion of non-alphabetic symbols in the text, such as numbers (references to prices, times, dates) or musical notes. In the particular case of Spain, where many early film plots were adaptions from lyric theater, and where there was a strong musical-dance tradition, Spanish film magazines often included sheet music to popular zarzuelas (plays set to music).

In addition to the formatting complexities of the original analog form of historical periodicals, there are particular challenges in working with non-anglophone languages. For example, in Spanish diacritic marks are frequent, dashes are used for dialogue transcriptions, and there are a greater number of punctuation marks pertaining to exclamation and interrogation (i.e. ¿?, ¡!). Thus, finding suitable computational tools was difficult, especially as concerns free, open-access software that could perform accurate optical character recognition (OCR).

Adding yet another layer of difficulty was the varying digitization quality of the magazines we consulted, and the lack of availability of plain text files. The digitized periodicals in the repositories we consulted provided downloadable PDF texts that required conversion into plain text. Thus, we needed to create our own corpus of plain text files, a task entailing considerable effort, particularly where keyword-based searching was not possible due to the poor quality of the scanning. In addition to this, we had to manually perform post-correction on the OCR output, since significant issues arose with incorrectly recognized characters and layout formatting (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, OCR software is notorious for struggling with layout, particularly as it pertains to multiple-column periodical formats where images are interspersed with the text (Daems et al. 3). Given how time-consuming text preparation is, in these situations it is useful, and the only logistically feasible option, to work with focused corpora. Thus, for our exploratory case study, we chose to center on one magazine (in this case, Popular Film), and to focus our efforts on only some sections (here, fan mail and reader contests).

Hoyt et al.’s ‘toggling’ method becomes more imperative when considering early, understudied film industries where there are few studies to help guide computational research and contextualize the patterns picked up through macro methods. Thus, it was necessary for us to limit our computational approach to Spanish film print culture to a small data set, since distant reading would not have yielded a reliable, totalizing conclusion at this early stage of the study. Our analysis fundamentally depended on our human eyes to carefully and thoroughly read each individual magazine issue. Working with the media specificities of periodical culture, where material was produced and consumed in installments which built on one another in consecutive sequences, made it important for us to read as readers read, in the order they read, at the time the magazines were published. As will be illustrated ahead, doing otherwise—reading only distantly and relying on the algorithmic methods of keyword-based searching of the digitized archive—ran the risk of decontextualizing the materials into inaccurate and inauthentic bits of information. Even discovering the treasure trove of fan photos that were published was due to the manual page-by-page reading of these magazines. By closely reading these issues as film fans would have, we were able to detail instances of the ways magazines coached their readers to be devoted fans, identify special notes to readers, determine if and when pen names were used by readers in their correspondence to magazines, and scrutinize the photos of stars as readers would have.

Lastly, a mixed methods approach is particularly necessary for interdisciplinary collaborations involving research members unfamiliar with the language of the primary material and its cultural context (in this case, Spanish, and the cultural milieu of Spain’s early cinema history). The required hard work that is manual in nature (e.g. reading each individual magazine issue, creating tabular data for digital analysis, etc.) compels us to accept that some projects like these take time, entailing immersion both with the media texts in question (magazines) and the broader cultural context.

Tracing & Visualizing Reader Demographics of Popular Film

By the second decade of the twentieth century, cinema in Spain had become a mode of entertainment boasting wide networks of distribution and projection. A specialized illustrated press devoted to cinema had begun as early as 1907 with magazines such as Cinematógrafo (1907, Madrid), Arte y Cinematografía (1910-36, Barcelona), El Mundo Cinematográfico (1912-1927, Barcelona), and El Cine (1912-1935, Madrid).[6] During the 1920s, with nearly eighty film magazines circulating the peninsula (García Carrión, “Spanish Modern Times” 198), these publications were affordable—costing between 20 to 50 cents, or less than half an hourly wage[7]—and easily accessible, distributed via mail order subscription and available in kiosks, stationary shops, mobile shop stands, and cinemas (Woods Peiró 181).

We chose Popular Film for its breath and popularity, and for its widespread availability in digitized form across various online repositories (Filmoteca de Catalunya, Biblioteca Digital memoriademadrid, and the Hemeroteca Digital de la Biblioteca Nacional de España). Published in Barcelona from 1926-1937, Popular Film was a weekly magazine with national and international distribution that came to publish more than 500 issues (García Carrión, Por un cine 88). With varied content ranging from articles on fashion, beauty product advertisements, interviews with stars, directors, and literary writers, film commentary and reviews, gossip columns, and critical essays on the state of the domestic film industry (Vernon and Peiró 295), Popular Film played an important role in educating readers how “to consume cinema and be cinema fans” (Vernon and Peiró 179), knowledgeable in the inner workings of film creation and in how to be successful movie stars, and with insights into the personal lives of celebrities.[8]

Though data exists about film exhibition and distribution, as well as film premiers, in early twentieth-century Spain (e.g. García Fernández; Cabero), the scarcity of demographic data of early film audience composition which documents, for example, the sex or age of audience members (we have not found any such data), in parallel with a lack of demographic information about readers of film magazines (we have not found any such data), alongside an absence of magazine subscription records—the number of subscribers, length of subscription, or subscriber information (e.g. name and address)—renders the fan mail section, or Estafeta, a particularly rich archive to provide key insight into reader demographics. In the case of Popular Film, the Estafeta was a regular section featured in almost every issue. It was most often featured at the middle-point of each magazine, ranging in length but which most often was a small corner of the page (it eventually was overrun by the women’s reader correspondence page “Correo femenino”). Notably, the Estafeta featured editors’ responses to individual letter-writers (as opposed to the letters themselves) (Fig. 2). Included in editor responses was the name of the reader and the origin of their letter (e.g. city). In the instances in which readers were addressed by a pen name or alias (e.g. ‘un simple aficionado’/a simple fan, ‘el indomable’/the indomitable, ‘Clara Bow’),[9] or by their initials only, the gender-marked grammar (masculine/feminine) of the Spanish language used by the editor provided clues to the gender (male/female) of the letter-writer. However, it should be noted that where we were unable to determine their gender, 1/5 of letter-writers (20%) were marked as ‘unknown.’ Thus, the basis of forming our dataset of the Estafeta was marking the issue number, date of publication, respondent name, gender, and city/region.

A data visualization of the distribution of letter-writers, by gender, who received responses from editors that were published in the Estafeta, reveals that male readers inundated the magazine in numbers that far exceeded those of women (Fig. 3). The magazine’s fan male letter-writers constituted approximately 67% of correspondents (754/1132) (compared with women, at 13.4%).

This is a striking result for several reasons. We were not expecting this to be the case, since contemporaneous news coverage in the Spanish general press emphasized the presence of (middle-class) women and adolescents in movie theaters, leading researchers to argue that women and children were the primary consumers of film in Spain (Montero Díaz and Paz Rebollo 123, 125). Indeed, women’s increasing importance as consumers occurred as film was gaining an audience in Spain in the first decades of the century. The urban leisure culture of which movies were becoming a key component “relied in unprecedented ways on the active participation of women” (Kirkpatrick 66), with female consumers thus forming “a salient proportion of the mass audience that the film industry rapidly developed” (67). Moreover, film historians have provided sustained analyses of the progressive feminization of movie fandom in the silent period and have traced the gendered discourse of film magazines in the 1910s and 20s, particularly in the United States, “and the degree to which these magazines increasingly spoke to women” (Orgeron 3). Parallel to this trend, Popular Film had a significant portion of fixed sections dedicated exclusively to women, increasingly providing more content ranging from cooking recipes, general beauty and relationship advice, articles about fashion, and beauty product advertisements. The magazine also boasted having the most women correspondents in its staff (García Carrión, Por un cine 88–89 nt. 132). Yet, in spite of the increasing content directed to women, our results demonstrate that men disproportionately contributed to the reader correspondence section, and as we will see, to reader contests.

Returning to our analysis of the Estafeta, with access to the names of the locations from which readers sent their letters, we also decided to look at the spread of the readership around and beyond the Iberian Peninsula. First, we extracted unique locales from our dataset, after which we automatically determined their latitude and longitude using Wikipedia parsing (in Wikipedia markup, <span> tags and the “latitude” and “longitude” classes are responsible for these parameters, respectively). If we could not determine a location automatically, we added the locale and all relevant information manually. As a result, we had a total of 168 locales in our dataset. In addition, we also collected statistics on how many letters came from which locale. Adding these to our dataset allowed us to mark points on the map built in the RStudio program with the help of the parzer (responsible for parsing geodata) and leaflet libraries (allowing us to visualize geodata) and to determine the “weight” of the locale in the corpus of letters. We attributed the highest weight degree to those locations from which the editorial staff of Popular Film received more than 48 letters; the lowest weight, in turn, was typical for the places from which readers sent at most 3 letters.

A geospatial analysis of letter-writer origins demonstrates cinephile audiences beyond the large metropolises of Madrid and Barcelona, as in the middle-size cities of northeastern Bilbao (Basque Country) and Zaragoza (Aragón), the northwestern city of Valladolid (Castile & León), southeastern Valencia and Alicante, and southwestern Málaga (Andalucía) (Fig. 4). On occasion, some readers wrote from beyond the Spanish mainland, including from neighboring north African Spanish-colony Morocco (particularly Tetuán, Larache, and Ceuta), the Spanish Canary Islands (particularly Las Palmas), and Mallorca. The geospatial visualization underlines one surprising detail: Barcelona, the magazine’s home base and an important and powerful center of early film production, exhibition, and distribution in Spain until about 1923 (Pavlović et al. 6-7), did not produce a majority of letter-writers. One possibility to account for this anomaly is that Estafeta entries addressed to ‘Ciudad’/city (about 10%) may be a reference to the Catalonian capital; there was also about 29% of editor responses that did not include a city or regional reference, and we marked these in our dataset as ‘not listed.’

Topic Modelling Fan Mail: Subscribing to Celebrity Craze

As readers wrote from all over Spain, topic modeling Popular Film’s fan mail section provides a broad snapshot on the issues and subjects that most interested readers. Topic modelling is a method stemming from text mining, “a research practice that involves using computational analysis to discover information from vast quantities of digital, free-form, natural-language, unstructured text” (Zubiaurre and Kurtz 119). From text mining, topic modeling allows researchers to summarize topics of interest by identifying words that tend to appear together and in close proximity (120).

To build the corpus of texts for topic analysis, we recognized the Estafeta section from the digitized numbers using ABBYY FineReader, resulting in 93 plain text files (corresponding to the number of issues featuring the Estafeta, out of 175 total issues consulted) and a total of 34,765 words in the corpus. These were subsequently manually proofread and “cleaned” of irregular spacing, inconsistent accent-marking and punctuation, name misspellings, and mojibake. The following preprocessing of texts consisted of basic steps: first, we lemmatized the corpus using the python library spaCy, which supports processing of Spanish language, and second, we eliminated punctuation and “stop words.” Since we were interested in examining content words (nouns, adjectives, verbs) rather than function words (articles, conjunctions, prepositions, pronouns), the latter made up the majority list of “stop words.”

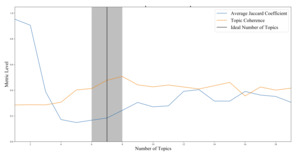

Using the preprocessed corpus, we built topic models based on the popular Dirichlet Latent Distribution algorithm (LDA) using MALLET software. As an input, the algorithm receives the texts and the number of topics to be detected in the corpus. As an output, it produces lists each consisting of the most typical words within the corresponding topic. To determine the optimal number of topics, we set the range of possible values of to be from 1 to 20. Then we built a separate LDA model for each number of topics in this interval. As a result, for each between 1 and 20 we got lists of words defining topics for the th model (one list for the first model, two for the second one, and so on). After that we used two approaches to select the ideal topic number from this range.

The first one is based on the comparison of each pair of neighboring LDA models (one topic LDA model vs. two topics LDA model, two topics LDA model vs. three topics LDA model, etc.), using the average Jaccard similarity coefficient. This coefficient helps check the degree of topic overlap and define a moment when the extraction of a new topic is excessive. The lower the coefficient of topics similarity the better, since this means that the topics are more heterogeneous. Consequently, if comparing the th model with the th model produced a value greater than in the previous step (when comparing the th model with the th model), then is the optimal value of the topics. According to this measure, the ideal topic number for our corpus equaled 7.

To confirm this value, we used the second approach, founded on the results of Topic Coherence measurement. In comparison to the Jaccard coefficient, the Topic Coherence method estimates the degree of semantic similarity between high-weighted words inside one topic and helps to define whether the topic is “high-quality.” The “high-quality” in this case means that all the words in the topics are more or less from the same semantic field. To calculate the coherence of each topic, we count the semantic relatedness of each pair of words from the topic and sum these values. For each pair of words, the value will be high if the words often co-occur in the texts, and low if they are more often found separately.

Next, we average the coherence scores for all the topics in a given model (the 1st LDA model will have one score, since it consists only of one topic, the 2nd LDA model will have an average of two scores since it is comprised of two topics). Selecting an excessive number of topics will result in topics with a random set of words, and hence a low coherence score. As a consequence, the average coherence will decrease, which means that the point of optimum we are interested in should be reached at the maximum of the average. If we look at the plot (Fig. 5), we will discover that the optimal value of the coherence score is at the same mark as the value obtained by calculating the Jaccard coefficient, which means that this is an ideal number of topics for this collection of texts.

With the heuristics described above, we detected 7 topics in our corpus and represented each of them as a word clouds formed of 150 of the most weighted words in each. Below we discuss the most telling of these topics, some of which emerge as among the most frequent, and what they reveal about readers’ interests (Fig. 6). Overall, the thematic trends discussed below emphasize that readers were eager to 1) learn about, and reach out to, their favorite stars, and 2) become magazine subscribers.

Topic model no. 6, most prevalent in the Estafeta’s first year between issue numbers 3-62 (Aug. 1926-Oct. 1927) and prominently featuring words such as ‘California’ and ‘New York City,’ among others, reveals readers were eager to send fan mail directly to film celebrities. Male readers inquired most for the address (‘dirección’) of Hollywood stars (women and men), and editors most frequently directed readers to the addresses of Paramount, Universal, and MGM headquarters. Topic models 3 and 7 suggests that readers were also eager to learn the names of stars/protagonists (‘estrella’/‘protagonista’) of various films and the studios (‘estudio’) they pertained to, and sought advice about the language in which they should direct their fan letters, visible in topic model 7 in such references to Spanish (‘español’), Castillian Spanish (‘castellano’), know (‘saber’), and speak (‘hablar’). Though a significant disadvantage of topic modeling is that word analysis often separates words that tend to appear together, such as names, and that there is no capitalization of these (Bonmatí Gonzálvez 130, nt. 17), we were able to piece names together and learn who some of these stars were. According to topic models 3, 6, and 7, they were Gloria Swanson, Norma Talmage, Lili Damita, Bebe Daniels, Douglas Fairbanks, Mae Murray, Greta Garbo, Mary Pickford, and the romantic duo Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. Though male readers exhibited a transnational fandom in their inquiries about Hollywood stars, they were also invested in the local industry and eager to connect with Spanish-speaking actors they could write to in Spanish, visible in the references in topic model 7 to Antonio Moreno, Ramón Novarro, Raquel Meller (in her role as ‘Carmen’ in the 1926 film of the same name), and Manuel San Germán, a protagonist of the Spanish-hit Malvaloca (1927), whose Madrilenean home address (‘San Bernardo 5’) appeared constantly throughout the Estafeta. Overall, reader enthusiasm to write to celebrities reflects the magazine’s efforts to encourage fans to write to stars, regardless of the fan’s cultural, geographic, and even linguistic origins.

Male readers were also eager not to miss a special issue of Popular Film and were keen to regularly read the magazine by becoming subscribers. Topic model 2, appearing rather consistently in spurts throughout the entire corpus but more intensely at end-of-year and new year issues (between issue numbers 51-72 and 125-131), shows that readers often inquired about subscription information (‘suscripción,’ ‘importe’/price), particular issue numbers (‘número’) (such as issue number 5, dedicated to Rudolph Valentino following the announcement of his death in the fourth issue), and an interest in special end-of-year issues, such as the 100-page 1928 almanac edition, advertised in no. 72 as containing “numerous portraits in rotogravure of the brightest stars of foreign and national cinematography; artistic photographs of the most beautiful women on the screen; caricatures of great film artists, and literary works” (17).

Featuring the most frequent items throughout the entire corpus of the Estafeta was topic model 5. Yet these were not revealing, consisting of grammatical elements—auxiliary verbs such as ‘be’ (ser) and ‘have’ (haber) and determiners/pronouns such as ‘that’ (ese) and ‘one’ (uno). However, we note the presence of the plural possessive ‘nuestro’ (our) suggests an effort to reader inclusivity. Indeed, Spanish film magazines constructed an inclusive network of fan culture through generic reference with the definite article, such as “the spectator” or “the public,” and the possessive first-person plural “our readers” (masculine gender forms by default in Spanish). This was complemented by a patent effort to directly address women and men, through gender-marked suffixes, such as feminine amiga lectora “reader friend” and masculine lector amable “amiable reader.”

Network Analysis of Popular Film’s Photo Contestants: Young, Aspiring Actors-Sportsmen

In addition to fan mail, another key mode in which male readers participated in fan culture was through magazine reader contests. Demonstrating a remarkable mastery of films and stars, male readers bombarded film magazines with entry ballots to reader contests, ranging from naming and visual identification contests to puzzles and writing competitions. A closer look at announcements of contest results reveals that male readers cultivated keen star knowledge since they often won first or second place in these contests, or were featured in most numbers as having correctly guessed answers.[10]

In addition to demonstrating their expertise on film stars, male fans displayed ambitions for stardom and fan creativity in their participation in a very different kind of reader contest: the photogenic, or star-search contest. Compared with mail inquiries or reader contests such as writing competitions, the concurso fotogénico involved a deeper kind of personal participation, as it spoke to the professional aspirations of movie fans. In her consideration of the star-search contest in the United States, Marsha Orgeron has argued that this was “the ultimate and in some ways most radical act of sanctioned participation” (4) in that it most intensely “appealed to the transformative fantasies of movie fans” (15).

To entice readers, these contests played into the allure of easy celebrity by promising the possibility of instant fame with the pledge of acting contracts to the victors, to be chosen by readers by mail-in vote (though the prospects of these contest winners usually never materialized). Unlike similar contests abroad, those in Spain had no set age limits (e.g. that contestants had to be between 18 and 30) nor were they geared to women only.[11] In fact, the contests were actively aimed at all sectors of Spanish society, including children and teenagers, by promising two winners, one male and one female reader. Strikingly, in four “photogenic” star-search contests run between 1922-1930, among the magazines Cine-Revista, El Cine, Popular Film, and Siluetas, featured male fan photographs far outnumbered those of female contestants, forming a whopping 79% (282/358) of total published photos across all four magazines (Table 1).

Particularly notable for the number of male participants is Popular Film’s star-search contest ¿Tengo condiciones de ser artista de cine?/“Do I have the conditions to be a film star?” which ran over a six-month period between 1926 and 1927. Readers residing anywhere in Spain (regardless of nationality) were invited to send two photos, a bust and full body picture, together with information pertaining to their age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, sports they played, intellectual abilities, and artistic experience. This information formed the basis of two datasets, the first of which contains the metadata of the magazine and information about the name, gender, and age of all contestants, while the second is devoted exclusively to male contestants and includes more complete personal data on height, weight, eye color, hair color, and different types of hobbies.

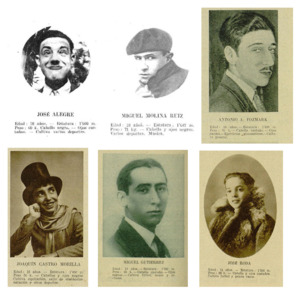

To entice readers to participate, the magazine promised that the winners would be cast in a future film (though this never actually transpired). As it turns out, adolescent boys and young men—primarily between the ages of 14 and 22 (160/196 male contestants, or approximately 82%) (Fig. 7)—flooded the publisher with photographs, forming an overwhelming 82% (196/240) majority in contestants whose photographs were published.[12] A data visualization makes it easier to observe, in a systematic way, the increasing number of photographs of male readers as the competition progressed (Fig. 8). While we don’t know the total number of photos that the magazine received from readers (male & female), a closer look at an editor’s response to one letter-writer indicates that the magazine received over 1,500 photos.[13] Given the competition’s success, one suspects that this estimate is likely to be true and that the magazine simply didn’t have the space to publish all photos, suggesting that editors made a selection of reader photos to publish, rendering the featuring of male reader photographs even more remarkable. Following the lead of the first four reader contestants to be featured in the contest—who were all adolescent boys and young men (notably, the first contestant was a 12-year-old Manuel Bernal de los Santos, the second a 14-year-old Bernardino Alonso del Olmo)[14]—male readers were overwhelmingly featured in full-page spreads of the magazine (Fig 9).

Depicting creative versatility, reader photographs often emulated the expressions, postures, and costumes of stars, including comic and serious poses, front-facing and side-facing portraits, and elegant dress (Fig. 10). With professional-looking photographs, and given the way they looked and dressed—clean haircuts, suit and tie, luxurious-looking fur coats, bow-ties, pocket squares, or top-hats—most male contestants appear to be upper middle class or of aristocratic backgrounds. Attire alone, however, can be misleading about the social classes of the magazine’s male readers, since appearing glamorous was part of the goal in emulating the grace and style of movie stars (Juan 207).

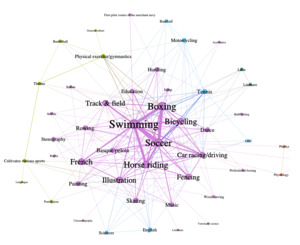

Offering more concrete clues is a network analysis of the sports and intellectual-artistic experiences that male fans listed with their photo submissions. To prepare the dataset, we manually created an Excel spreadsheet listing each hobby and intellectual/artistic experience of each individual contestant (ranging from 1-7 sports & 1-4 intellectual/artistic experiences for each reader-contestant, when listed). For example, among sports and intellectual/artistic activities were “boxing,” “swimming,” “soccer,” “dance,” “theater,” and “literature.” We note that for the more consistent network of hobbies we minimally modified the descriptions of intellectual/artistic experience and united some under a more uniform label. For example, the “Music” category includes descriptions by reader-contestants such as “8 years experience with piano, harmony, and composition,” “Student of Alicante’s Municipal Band,” and “Violin professor,” while the “Education” category included such self-descriptions as “High school education,” “Advanced in primary education,” and “Secondary school education.”

Using this list of hobbies and experiences, we generated a co-occurrence matrix, which consequently became the basis for the visualization of our network (Fig. 11). In Gephi software, we got an undirected graph of 49 nodes and 234 edges, where nodes are the names of hobbies and edges are their co-occurrence in a list provided by one person. The size of the nodes depends on the number of connections with other nodes, while the weight of the edges represents the number of intersections of a pair of nodes. The network is colored according to the modularity measure that allows us to detect different communities in the graph. Thus, after the calculation of this measure, we discovered 5 main groups of hobbies, inside which sports and other activities have the densest connections. An important feature of this network is that it does not represent such a category as “cultivates various sports,” a note that accompanied approximately 24% of male contestant photos who did not list specific sports or intellectual/artistic experiences, and, consequently, had no nodal connections to other hobbies. The same pertains to those we marked as “not listed” (13%), when male contestants had no sports or hobbies included with their published photo.

The sports that male readers listed suggests a more nuanced mixture of readers than their sophisticated poses in front of the camera first suggests. In Spain, sports were an urban phenomenon “that involved sharp class distinctions” (Cuesta 331). Alongside prestigious activities such as drawing or knowing a foreign language like French, bicycling, horse-riding, fencing, and car-racing was practiced by the middle-upper class and aristocracy. Yet soccer and boxing, two of the top sports mentioned by readers, was a modern mass-spectator sport in Spain that “brought the lower-middle class and the working class into the sports world” (Cuesta 331), suggesting that a portion of male readers may have pertained to these sectors.

What Lies Beyond the Word: Reading Contextually with Our Eyes

Digital methods such as text mining, topic modeling, and network analysis work well as exploratory techniques that can reveal clues and patterns. Yet while digital methods may make it easier to mine large amounts of data, the challenge remains of framing and interpreting that data, particularly in areas of study without prior research to draw from. Unsurprisingly, a manual reading of the magazine’s individual issues provided a more complete picture of the magazine’s readership and insights that our computational text analysis of the Estafeta alone would not have detected. While we don’t know how many letters the magazine actually received (on a weekly/biweekly/monthly basis), occasional ‘special notes’ reminding readers to become subscribers with the benefit of gaining priority in receiving responses from editors make reference to having to respond to “more than 500 letters.” Although we also don’t know the total number of photos submitted to the star-search photo contest, coverage of the contest’s outcome in later issues provided some clues to the remarkable size of voter participation: an announcement of the upcoming results in no. 56 mentions that votes are in the “several thousands” (p. 16) and the announcement of the winners was accompanied by the number of votes they received (14,273 for the male winner, and 18,615 for the female victor).[15]

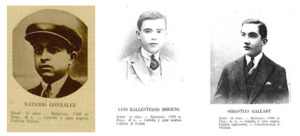

Fan photos provide a treasure trove for film audience studies in authenticating the existence of a community of movie fans. Where fan letters have been questioned by film historians as to their authenticity and accurate reflection of magazine readers (e.g. Fuller-Seeley 153), a close-reading of the Estafeta revealed that many readers writing to the magazine were also featured in the photo contest, connecting the names to the faces. As we manually read each editor response and noted the names of those readers who appeared multiple times, we were able to identify the names of those whom we may refer to as ‘super fans’—readers who wrote more than once to the magazine and who submitted a photo that was published. These male super fans wrote not only to ask about their favorite stars, but were anxious to know whether their photos had been received and when they would be published. This was the case with 15-year-old Nazario González from Elche and 16-year-old Luis Ballesteros from Málaga (Fig. 12), who each wrote to the Estafeta editor on at least three occasions about the photo competition and inquiring when the magazine would create a new contest they could participate in.

With this information, we were then able to do make use of the affordances of computer keyword searching for particular names in other magazines, learning that some of these super fans were simultaneously writing to various magazines at once. 16-year-old Sebastián Gallart wrote repeatedly to Popular Film in 1927 with subscription questions, but also occasionally to the reader opinion section “Our readers say” of the Madrilenean film magazine La Pantalla. One of Gallart’s opinion letters was deemed “the best,” winning first prize in La Pantalla’s third issue. Demonstrating his keen enthusiasm for cinema, the young teenager praises the black-bottom dance routines in the Hollywood motion picture Cabaret, criticizes Gilda Gray’s at times “exaggerated” performance in the film, and applauds Tom Moore’s role as the detective in love.[16]

Lastly, our topic models of the Estafeta did not capture the fervency of male readers in presenting themselves as devoted and informed movie fans keen to share opinions and critical expertise. A close reading of the first twenty issues of editor responses to fan mail reveals, early into the magazine’s lifecycle, that male fans exhibited hobbyist dispositions and creative inclinations by regularly corresponding with the publication to pitch ideas to the editorial board and requesting to collaborate with the magazine to publish original work. Further examination of the magazine’s early issues demonstrates that the publication promised to be a site of cinephilic exchange for a community of movie fans, where readers could share with one another—and prove to each other—their critical expertise and creative talents by enticing readers with the opportunity to voice their opinions in their new section “Nuestros lectores colaboran”/Our readers collaborate.

The section, short-lived in that it appeared in only 13 issues over six months between December 1926 and May 1927, featured brief prose essays, poems, and short stories, and encouraged readers to submit “brief works that are sent to us spontaneously” (no. 20, p. 2). Readers debated the state of the Spanish industry, praised and critiqued films and stars (e.g. Ben-Hur, Mae Murray), and commented on the artistic divide between theater and film. Of the 28 readers who were featured, only two were women; several male readers were featured multiple times, including an L. Linares Lorca, a reader who had written to the Estafeta inquiring about whether his work was ‘publishable’ and who would go on to become a regular contributor to the magazine’s content, as well as to other contemporaneous film magazines, including El Cine. The brief lifespan of the new section and the interruption of inquiries about collaborating with the magazine suggests efforts to curtail the excessive interaction of some readers with the magazine.

Conclusion: New Sources of Evidence

This project contributes to an archaeology of cinema fandom broadly, and Spain’s early film fan culture specifically, by turning to digital methods—text mining, modeling, data processing, GIS mapping, data visualization—to trace male movie fans in Spain. As an exploratory case study, we considered fan interactivity with the magazine Popular Film. In particular, we considered reader participation in two particular sections of this magazine: the Estafeta, or fan mail section, and the reader photo contest, “Do I have the conditions to be a film star?” Our results counter any assumptions that male moviegoing audiences, unlike the star-struck female fan, were composed of emotionally detached spectators or who were uninvolved in celebrity consumer culture. Analyses of correspondence and photos demonstrate that Spain’s early cinema fan base was unequivocally composed of a strikingly large proportion of readers who were male and who were actively ardent fans. That male readers actively engaged with the magazine by sending mail inquiring about movie stars and how to reach them and eagerly participating in the star-search photo contest, appears to suggest that male readers were remarkably invested in celebrity consumer culture.

Methodologically, in conducting this study, we reflected on the challenges of digital approaches to pursuing historical periodical research and advocated for the affordances of a mixed macro-micro approach entailing distant reading and traditional textual studies of close reading. By adopting a hybrid framework, digital methods provide new opportunities to discover evidence of male movie fans in Spain.

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/K8R6MV

This and all subsequent translations are our own.

This project was made possible by an ACLS/DRIVE Postdoctoral Fellowship in Humanities-Based Data Studies and Digital/Social Transformation at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2020-2022) awarded to Anna Torres-Cacoullos. A special note of thanks to the Filmoteca de Catalunya for access to the archive in Barcelona, and to the graduate student assistants involved in various stages of this project, including Morgan Lundy for helping jumpstart the digital exploration of Spanish magazines, Lázaro García Angulo for astute readings and invigorating discussions and, above all, Liza Senatorova.

See, for example, Kathryn Fuller-Seeley (1996); Shelley Stamp (2000); and Diana Anselmo-Sequeira (2015).

See Courtney Andree’s consideration of early male movie fans, in the United States context.

The so-called ‘Silver Age’ of Spain (in Spanish, ‘La Edad de Plata’), is a term commonly used in conventional literary histories to refer to the period of 1898 to 1939 characterized by flourishing of artistic and cultural production, alongside a burgeoning urbanization and a boom in mass culture. The term was popularized by José Carlos Mainer’s La Edad de Plata (1902-1931). Ensayo de interpretación de un proceso cultural (1975). See Antorino (162), and Zamostny & Larson’s Kiosk Literature (2017).

The dates of publication for El Mundo Cinematográfico are inconsistent across various record sources, some indicating, for example, a start date of 1915 (see López Yepes 164). We draw our dates from Palmira González López (928).

Speaking to the affordability of cinema’s print culture, Emeterio Díez notes that a worker in Madrid circa 1925 earned 1.25 pesetas per hour (49).

See Eva Woods Peiró’s study of the ways film magazines in Spain “tutored” their readers to be knowledged film fans (179).

Popular Film No. 19 (p. 11), No. 29 (p. 11), No. 123 (p. 8), respectively.

For example, based on the names listed of readers who guessed correctly, Cine-Revista’s 1922 competition “The masked aces,” (e.g., the masked Carol Holloway and Sessue Hayakawa), featured 28/46 male readers (61%) (no. 33, p. 4), Cine-Popular’s 1923 cropped-eye puzzle game, “Whose eyes are these?” had male readers winning 1st-4th place (no. 111, p.15), and Siluetas’ 1930 rhombus puzzle contest listed 18/23 male readers (78%) (no. 15, p. 10).

Richard Abel has argued that American local talent contests targeted “mostly young women” (134), and Myriam Juan has noted that in France these competitions were often “for women only” (204).

The published photographs featuring male readers participating in Popular Film’s photo contest can be found on p. 16 in issue numbers 17-18 & 20-22; on p. 12 in issue numbers 23-33; and on p. 16 in issue numbers 34-44.

Popular Film, No. 91, p. 10.

The photographs of these first two contestants can be found in Popular Film’s issue no. 17 (p. 16) & no. 18 (p. 16), respectively.

Popular Film, no. 57, pp. 4 & 5, respectively.

“Nuestros lectores dicen,” La Pantalla, no. 3 (2 Dec 1927), 39.

_from_our_first_attempt_at_plain_text_conv.png)

.png)

__in_*popular_.png)

_in_*pop.png)

_(p._16)__featuring_numero.png)

_from_our_first_attempt_at_plain_text_conv.png)

.png)

__in_*popular_.png)

_in_*pop.png)

_(p._16)__featuring_numero.png)