The library cards and logbooks preserved in Sylvia Beach’s papers confirm the conventional image of Shakespeare and Company: the bookshop and lending library sat at the very heart of interwar modernism. The shop conjures images of Ernest Hemingway perusing the bookshelves and Gertrude Stein stopping by from her home a few streets away. James Joyce, George Antheil, and André Gide are among the many names we associate with the bookshop’s dazzling community. And the Shakespeare and Company records reflect their presence.

But the records, digitized by the Shakespeare and Company Project, also reveal a different community—one not present in these images of the Lost Generation. The names of Aimé Césaire and Paulette Nardal, architects of the Négritude movement, also appear in the records: Shakespeare and Company was a node in the vast and vibrant network that defined the rise of Black internationalism in Paris, a point of contact for Black intellectuals from both sides of the Atlantic.

This article explores Shakespeare and Company’s place in this network. It begins with the Harlem Renaissance writer and artist Gwendolyn Bennett, and how her relationship with Shakespeare and Company reveals a porousness between the “Lost Generation” and “Paris Noir” in Beach’s bookshop. The article then examines how Beach sought to connect writing from Harlem to Black intellectuals in Paris, who were in the process of creating a new anti-colonial articulation of race.

In June of 1925, Gwendolyn Bennett arrived in France. She came to Paris as a burgeoning talent of the new Renaissance of Black art that had begun to flower in the United States. Her poem “To Usward” was published in both The Crisis and Opportunity Magazine in 1926. As an artist she had gained early recognition as well: her work was selected as the cover for the Christmas edition of The Crisis that year. Bennett was twenty-two when she arrived, alone, in Paris to study art at the Académie Julian on a $1,000 scholarship from Howard University.

Bennett’s experience was perhaps not exactly what she had been expecting when she departed from New York. She was certainly enchanted by the French capital. In a diary entry from her first week in Paris, she wrote “There never was a more beautiful city than Paris . . . there couldn’t be! . . . One has the impression of looking through fairy-worlds as one sees gorgeous buildings, arches, and towers rising from among mounds of trees from afar” (Diary). But this awe of the city was punctured by the fact that she felt homesick for America. She yearned for a community, which she found hard to find in Paris. Shakespeare and Company was just down the street from her first address in the city and became a place of note and connection for her. In August of 1925, she wrote Countee Cullen that she had “joined a very interesting little, private library here - ‘Shakespeare and Co.’ by name” (Letter). Indeed, the name “Miss Bennett” shows up in Beach’s logbook in June of 1925, the same week that Bennett arrived in Paris. Her private writing reveals her attachment to Beach’s shop (Lending Library Logbook). In one August entry in 1925, she wrote about reading Troubadour: An Autobiography (1925) by Alfred Kreymborg. Reflecting on the book, she wrote, “On Reading in Troubadour about Shakespeare and Co I felt the warmth of contact with the author because I know the place and haunt it” (Diary).

Bennett’s language when describing the bookshop is so evocative that it fills in some of the gaps in what we know about her sojourn in Paris. Bennett’s lending library card has not been preserved, so we can’t know what she read while she was there, or how often she frequented the shop. But the choice of the word “haunt” conjures such a specific image, of her returning again and again, lingering in the bookshop down the street. “Haunt” also imbues this space with a magnetic quality, implying that she found herself called to this environment. The word “warmth” also stands out in Bennett’s diary. Chilly imagery permeates Bennett’s diary when she discusses Paris. She finds Paris brilliant but cold. Cool gray rain unsettles her during early weeks in the city; her descriptions of her loneliness are spiked with iciness. The “warmth” of the shop stands out in contrast. The importance of the shop for her is also visible in a guide to the city she created for a friend. In her short guide, she recommends Shakespeare and Company as one of only a few locations her friend must visit (Untitled List). Miscellaneous papers and unpublished writing found at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture show Bennett continuing to reflect on Shakespeare and Company and Beach with fondness as her career progressed in New York (“I Have Seen…”).

Bennett’s correspondence discusses some of the books she borrowed at Shakespeare and Company. In one letter to Langston Hughes she shared that she had found Jean Toomer’s experimental Cane (1923) at the bookshop (Barton). Perhaps she used her subscription to read the writers she felt so disconnected from when she moved abroad. After all, one of the causes of her homesickness was that she had the distinct sense that she was missing out on the flourishing of Black art at home. In a letter to Cullen she expressed that the shop was interesting because Beach featured all “newer” writers. In that same letter, she shares that she had been able to purchase Ulysses (1922) (Letter).

Bennett’s writing shows that her experiences at Shakespeare and Company were not necessarily congruent with the broader dynamics she encountered in Paris. Her story “The Wedding Day” (1926) examines the way that Paris was segregated, expressing an outrage at the treatment of Black Americans in Paris that is not present in her extant diaries. The story is a biting critique of the way that American racial politics were imported to Paris, as Americans, both Black and white, started to populate the city after World War I. The protagonist is Paul Watson, an African American man in Montmartre, who purposefully keeps his distance from white Americans who’ve come to stay in the city. When he does encounter white Americans, he is met with familiar slurs and violence. Despite his caution, he falls in love with a white American woman, Mary, who when he first meets her is destitute. This is not a story of how racial barriers could be surmounted in Paris in a way they could not be in the United States. On the day of Paul and Mary’s planned wedding, he finds a note instead of his bride: “white women just don’t marry colored men” (28). Despite France’s reputation as “color-blind,” Bennett’s short story reveals a society where American prejudice remains inescapable. While Bennett’s writing speaks to racism between Americans, her own experience in France reflected prejudice and exclusion from French society. Bennett spent her year studying at the Académie Julian after facing rejection from the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts—a rejection she strongly suspected was due to her race (Barton).

Bennett’s story speaks to the experience of a generation of Black Americans in Paris. World War I brought African American soldiers to Paris in unprecedented numbers. For many of these soldiers, the experience of being in France was shocking. The relative acceptance they found in their French encounters served as a stark contrast to discrimination faced in the US Army and at home (Fabre, From Harlem to Paris 49). At the end of the war, some African American soldiers decided to stay in France, ultimately helping to create the enduring notion that there was racial equality in the country (Fabre, From Harlem to Paris 53). “Paris Noir,” as historian Tyler Stovall has called the Paris that African Americans inhabited, became an undeniable cultural force in the city. But while there may have been less open discrimination in France, the country was not a land of racial equality. In Paris, white and Black Americans lived separate lives, even when they did casually intermingle. As Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting writes in Bricktop’s Paris (2015), the separation between white and Black Americans was even more pronounced among women (11). Bennett captures this separation in her short story: the Black Americans live in a lively Montmartre community, a world apart from white Americans in the center of the city.

For this reason, Bennett’s description of Shakespeare and Company, traditionally understood as a “Lost Generation” space, poses new questions about the way that “Paris Noir” and “Lost Generation” Paris overlapped. To some extent, the Shakespeare and Company records confirm a separateness between the Black and white worlds in Paris. Based on information in the logbooks, books by Black authors were never bestsellers, and it must be noted that books with troubling, exoticizing, and degrading characterizations of Black people were circulated in the library. As Joshua Kotin and Rebecca Sutton Koeser note, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936) was even more popular than The Great Gatsby (1925) (“Top Ten Lists”). Yet when we follow Bennett’s trajectory through the bookshop, we gain insights into the broader relationship the shop had with Black American art. Bennett introduced Beach to Paul and Eslanda Robeson at a tea held at Shakespeare and Company (Bennett, Untitled List). This was a significant encounter. Paul Robeson would go on to be one of the most significant actors and performers of the twentieth century, known for bringing a new depth and humanity to how Black characters appeared on stage. Robeson’s political voice was as impactful as his stage voice, as he used his platform to promote his views on segregation, anti-fascism, and communism. Eslanda Robeson’s writing and research would lead to her own independent involvement in anti-colonial and anti-racist movements (Ransby). Bennett’s introduction sparked a productive relationship between the Robesons and Beach: that year Beach offered Shakespeare and Company to Robeson as a performance space. At one event, Robeson performed African American spirituals that he was preparing for his world tour (Weiss 38). Beach ensured that Robeson not only had a platform, but also fanfare and press as she invited reporters along with friends to his performance. Adrienne Monnier, Beach’s partner and the owner of the French bookshop La maison des amis des livres, covered Robeson’s performance in her literary journal Le Navire d’Argent (McDougall 56).

When the Robesons came to Shakespeare and Company, they already had a distinct vision for what Black art could do. In her biography of her husband, Eslanda Robeson captured his philosophy at the time of his tour: “If I can teach my audiences, who know almost nothing about the Negro, to know him through my songs and through my roles, as I have learned to know the sea without ever having been actually near it — then I will feel that I am an artist, and that I am using my art for myself, for my race, for the world” (59). Robeson envisioned his performance as an embodiment of Black American history and humanity, and saw art as a space through which justice and equality could be realized. Robeson’s performance at Shakespeare and Company was inherently political. If Bennett’s experience shows Shakespeare and Company as a welcoming space in Paris, her involvement with the Robeson performance illuminates a flow of ideas and art, from Harlem to Paris. This performance also shows Shakespeare and Company serving as a door between Black intellectuals in the United States and a transnational public in Paris.

Opening doors like these was significant not just for the Black Americans in Paris, but for the scores of Black thinkers and artists who arrived in Paris from across the French Empire. The interwar period was marked by an influx of men and women from France’s colonies. This influx was in large part a consequence of World War I, which had permanently altered the way the French Empire functioned. Over the course of the First World War, 500,000 soldiers were recruited from the colonies to fight in the French army while 200,000 colonial subjects were conscripted to work in France. The French decision to call upon the colonies provoked a reckoning of racial logic and Empire, as well as the idea of a “blood debt” that colonial soldiers created, “a new language” for colonial subjects to challenge their relationship with France (Boittin 78). In this way, a new space opened in metropolitan France as a means of paying off this debt. The presence of these new actors from France’s colonies fundamentally changed the culture of the city, making the French capital what Jennifer Boittin has called a “colonial metropolis.” The arrivals of these new groups in Paris created a parallel environment to Harlem where “people of African descent from a variety of classes and places converged and formed self-conscious communities” (Wilder 154). Through this convergence, a new hunger developed to communicate across cultures and languages, to realize a Black identity that existed beyond the barriers of nation.

Beach was evidently not only aware of this flow of knowledge between Harlem and Paris, but determined to help facilitate it. In 1937, she wrote across the Atlantic to the Friendship Press in New York for expert advice in curating her lending library’s carefully selected stock. “The French Negro students in Paris rely on my lending library to keep them in touch, as much as possible, with American Negro Literature” she wrote to the Press, showing a familiarity with the nature of the exchange occurring in Paris. “I have a number of very interesting books by poets and novelists, and studies on the subject of the problems of the American Negro,” she continued, “but not as many as I should like” (Beach, Letters 178–79). As Beach states, her intent in seeking out this writing by African American authors was to help connect Black English and French speakers.

Beach’s articulation of intention is significant. As both Black English and French speakers were aware, Black aesthetics had become a fad in interwar Paris. In the aforementioned Bennett story, she wryly marks time in Paris as before and after “colored jazz bands were the style” (“Wedding Day” 25). In her diaries she wondered why she had not met Carl Van Vechten, the white patron of so many Harlem Renaissance artists: “I suppose, though,” she remarked, “that I shall meet him when I return to America—that’s if his enthusiasm for colored folk lasts. I doubt it will though.” In a 1928 article in La Dépêche Africaine, Jane Nardal, a Martinician scholar who, with her sisters, were key figures in the Négritude Movement, critiqued the way that Black women in the city were seen as “exotic puppets” in the white gaze (2). In Colonial Metropolis (2010), Boittin describes the fad of the bals—the bal nègre, bal antillais, bal colonial, where white French people socialized with the city’s new Black residents—as often superficial and occasionally fetishistic (5). It is impossible to determine the motivations of everyone who checked out books by Black authors at Shakespeare and Company—perhaps some readers of Langston Hughes or Countee Cullen sought out these books due to the “tumulte noir.” But what we can tell from Beach’s letter is that there was a French-speaking Black audience at her bookshop and lending library, and that these books were to be there for them.

Shakespeare and Company records reveal that the “French Negro students” included the interwar period’s most significant writers about race. Logbooks and lending library cards reveal that Aimé Césaire signed up for a subscription in 1937 just before writing his masterpiece Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (1939). Paulette Nardal, sister of the aforementioned Jane Nardal, was also a member of the lending library. She has been called by scholar Brent Edward Hayes a crucial “cultural intermediary” between English and French discourses because of her creation of the bilingual journal Revue du monde noir (120). She also ran a salon, not far from Beach’s shop, where she hosted leaders of Black internationalism (Edwards 119–20). A “Damas” also shows up in the logbooks in 1935—possibly Césaire’s collaborator Léon Damas.

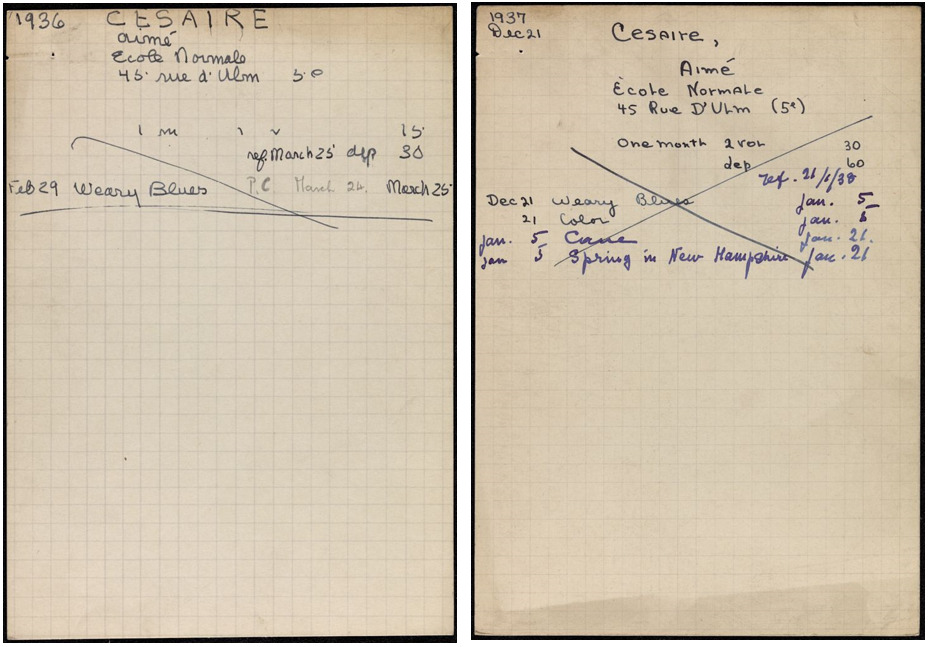

Unfortunately the Nardal and Damas lending library cards have been lost, and with them further insight into the ways that crucial ideas and texts flowed through Shakespeare and Company. But Césaire’s cards are extant (fig. 1). The cards offer an especially illuminating glance into not just Shakespeare and Company but also the larger literary world around it. Césaire first came to Shakespeare and Company in 1936, where, according to the records, he sought out new works by African American writers. Twice he checked out Hughes’s The Weary Blues (1926). Cullen’s Color (1925), Claude McKay’s Spring in New Hampshire and Other Poems (1920), and Toomer’s Cane (1923) filled out the rest of his library cards.

The very presence of Césaire’s cards offer insight into how sought after these books were in the 1920s and 1930s. Unlike some of Shakespeare and Company’s more transient American readers, such as Hemingway, who remembers scouring the bouquinistes to find stray English-language books, Césaire was well-connected to French institutions when he signed up for a subscription at Shakespeare and Company. As the address at 45 rue d’Ulm on his library card indicates, Césaire was a student at the École normale supérieure. By 1936, his resources would have extended well beyond the walls of his university. One year earlier he had formed the journal L’Étudiant noir alongside Léopold Senghor and Damas, which further connected him to a network of intellectuals in France. The fact that he joined Shakespeare and Company illuminates how difficult it must have been to access books by African American writers, and especially the writers of the Harlem Renaissance, in interwar Paris.

This ability to access African American writers was integral to the development of Négritude in Paris. “I remember very well that around that time we read the poems of Langston Hughes and Claude McKay,” Césaire recalled in a 1967 interview with the Haitian poet René Depestre. The “Negro Renaissance Movement in the United States,” he explained, was not a “direct” influence, but “created an atmosphere which allowed me to become conscious of the solidarity of the Black world” (87). Accessing the literature of the Harlem Renaissance was necessary to create this “atmosphere,” to foster this ability to think beyond the parameters of nation. For Paulette Nardal as well, access to Black writing from America was crucial. In December 1927, she wrote Alain Locke, seeking permission to translate The New Negro (1925) (Edwards 128). In September of 1928, the Shakespeare and Company records show that she had joined the lending library, where she maintained a membership for two years. The absence of Nardal’s library card is a great loss, since her presence at the shop raises tantalizing questions. Did she, like Césaire, use Shakespeare and Company as a resource for accessing books like Locke’s? Nardal expressed an interest in Harlem Renaissance authors such as McKay, Hughes, and Toomer (129). Books by all these writers were in circulation by the time she joined the lending library. Seeing Nardal’s name among these records, one also wonders if her Shakespeare and Company reading played a part in the La Revue du monde noir, which she created in 1931 with Léo Sajous. La Revue du monde noir was a bilingual journal: each piece appeared in both French and English, with the goal of opening new channels of communication between the English and French-speaking Black worlds.

It wouldn’t be surprising if Shakespeare and Company did indeed play a role in helping Nardal create her trail-blazing review. The bookshop certainly participated in the review’s circulation: Shakespeare and Company stocked and sold each issue of La Revue du monde noir in 1932 according to Beach’s logbooks (“Bookshop and Periodical Logbook”). As both Hayes and Sharpley-Whiting have argued, the role of the Nardals in the creation of Négritude has been neglected. Senghor, Damas, and Césaire have typically been characterized as the “fathers” of the movement, while the Nardal sisters have been cast to the side. Recent scholarship has reframed this narrative, crediting the Nardals as not merely “midwives” to Négritude, but among its creators. By circulating Nardal’s work, Shakespeare and Company’s role in this network came full circle.

The fact that La Revue du monde noir circulated at Shakespeare and Company also provides insight into the politics of the bookshop and lending library. As I have explored elsewhere, Beach’s feminist activism was foundational to the creation of Shakespeare and Company (“Secret Feminist History”). Beach had been a suffragist in the United States, and done feminist work in Spain and Serbia, where she worked for the American Red Cross after World War I. When she opened Shakespeare and Company, she had been a part of the feminist-socialist network in Paris. The principles of opening her lending library, which expanded access to English-language books, resonated deeply with her feminist work. As the data from The Shakespeare and Company Project has revealed, women were responsible for seventy percent of the book borrows at Shakespeare and Company. The circulation of Nardal’s journal, with its feminist politics, shows the way in which the shop continued to build on its feminist roots.

Shakespeare and Company closed during World War II. But Beach’s work to connect prominent Black intellectuals from the United States and France did not end. She used her cultural connections in Paris in the 1940s to help Richard Wright establish a foothold in Paris. As the Shakespeare and Company records indicate, Wright was on Beach’s radar years before they became friends in Paris. Beach apparently purchased Native Son (1940) immediately after its publication, as the book shows up in the lending library in 1940. In the few months the book was available, it was apparently popular—checked out at least five times between February 1940 and October 1941. Even if Native Son was only in circulation for a few months before Beach’s shop closed, an analysis of the readers illustrates the reach of the book. From August to September 1940, Simone de Beauvoir, who often used Shakespeare and Company to access contemporary American literature, checked out Native Son. Considering the significant relationship that Wright would later have with the existentialists, especially de Beauvoir, this early encounter is especially striking (Fabre, “Richard Wright” 48).

In addition to putting Wright’s book in circulation, Beach helped Wright interpret the impact of his writing in Paris. As Michel Fabre notes, Wright was quickly translated into French, in both Sartre’s Les temps modernes and by Gallimard. Beach’s insights into French readership allowed her to comment on the reception to his books, which she in part did through assessing the book’s popularity at La maison des amis des livres. In one of her first letters to Wright, she notes that Maurice Saillet, one of the booksellers at La maison des amis des livres, is waiting in anticipation for the translation of Native Son. Her letters also indicate that she helped Wright find an Italian translator for his work. In this way, Beach assisted Wright’s transition to Europe, a transition that would be definitive to the post-World War II community of Black writers and intellectuals who would settle in Paris.

In Sylvia Beach’s memoir, she writes that her goal of opening Shakespeare and Company was simple: she wanted to make English language “moderns” accessible in Paris. The way that Shakespeare and Company connected the Lost Generation has been explored in great depth. Through considering Shakespeare and Company’s role in a larger context of Black internationalist interwar print culture, this article has sought to explore Shakespeare and Company’s other networks. It is clear that Shakespeare and Company existed as a point in a constellation of literary institutions that arranged for the meeting of people and ideas in a way that contributed to internationalist thinking.

By exploring Shakespeare and Company in this new context, a number of other questions arise. Sylvia Beach considered Shakespeare and Company to be only one half of a literary world on the rue de l’Odéon. Her business and life partner Adrienne Monnier’s French-language bookshop and lending library, La maison des amis des livres, completed the world that they called “Odéonia.” If the records from Monnier’s lending library were placed alongside Beach’s, how would this portrait change our understanding of Black networks in Paris? How did the books stocked by Monnier compare to Beach’s? Among the names of Monnier’s subscribers might we find Damas, Senghor, and the Nardals? An exploration of the culture of Odéonia will not only yield a sharper perception of how these spaces functioned, but will offer insight into the complex, transnational world of interwar France.