Gertrude Stein “was disappointed in me when I published Ulysses,” wrote Sylvia Beach in her 1959 memoir; “she even came with Alice to my bookshop to announce that they had transferred their membership to the American Library on the Right Bank” (Shakespeare and Company 32). Stein’s move—from Shakespeare and Company to the American Library in Paris—has sustained the ongoing scholarly and popular representation of the two libraries as rivals, framing membership as an act of allegiance. And yet, the relationship between interwar Paris’s preeminent American lending libraries—which both opened their doors to patrons immediately after World War I, in a Paris that was becoming, but had not yet become, the heart of Anglophone modernist literature—is clearly more complicated. The lending libraries shared patrons and milieus, and when Beach had to give away Shakespeare and Company’s books in 1951, she gave them to the American Library, writing to its then-director, “I am glad to feel that the place for my books now is the American Library of Paris” (Letters 223).

Records from Beach’s library, historical newspapers, and the annual Year Book from the American Library in Paris (ALP) reveal connections between the two libraries that transcend simple rivalry.[1] In what follows, I trace the representation of the two libraries in the periodical press; compare their patrons’ locations and borrowing habits; and examine the tastes of Anglophone readers in Paris against Americans in the US. Modernist studies has increasingly replaced the model of the genius working in isolation with the idea of collaborative networks.[2] This essay asks that we extend our understanding of this cooperative atmosphere beyond individuals to institutions, retelling the story of Shakespeare and Company and the American Library in Paris to emphasize their similarities (and symbioses) alongside their differences.

Rivals or Peers?

Sylvia Beach herself seeded the idea that Shakespeare and Company and the ALP were in competition nearly as soon as her bookshop opened its doors. Writing to her mother in 1920, as the ALP struggled to sustain itself after its war-time financial support from the American Library Association expired, Beach reported “Miss Gertrude Stein says the great American Library rue de l’Élysée is going to fail for lack of funds she thinks, and I hope so I’m sure. It’ll be a glad day and hurrah for it” (Letter, in Wang 151).[3] Decades later, this narrative of a rivalry was cemented in both Shari Benstock’s and Noël Riley Fitch’s influential 1980s accounts of the Left Bank’s women. Despite little evidence beyond Beach’s comment to her mother to support it, this antagonistic framing has continued in contemporary scholarship: in 2014, even as historian Nancy L. Green acknowledged that the ALP was “of course not in direct competition with Shakespeare and Company,” she referred to the two bookstores as “rivals” and made much of their disparate memberships (38).

The local press emphasized the differences between the two institutions from their earliest years. In the “Paris American” newspapers—most prominently the editions of The New York Herald and The Chicago Tribune produced and published in the European city—Beach’s library was represented as the haunt of artists and intellectuals, while the ALP was described in prosaic terms. A 1921 Paris Tribune article titled “Literary Adventurer” introduced Beach to the paper’s readers as “a Maecenas for Paris writers, poets, and bookworms,” likening her to Rome’s most famous patron for the arts, while the Tribune’s reporting on the ALP focused on its quotidian operations, such as fundraisers, holiday closures, and membership costs (3). These differing depictions of the two lending libraries—one a site for adventure, the other a familiar comfort—remain evident in the 1929 travel guide Paris Is a Woman’s Town, where Beach’s bookshop is described as “a meeting place for young intellectuals and older ones too,” and the ALP is seen as “a cozy home-like place to browse about in on dour days” (188, 167).

Despite their different reputations, the libraries shared many characteristics. Both were founded by Americans with the aim of serving Paris’s Anglophone residents and the French; both operated on slim margins, privileging readers and books over profits; both charged similar rates for borrowing privileges and allowed visitors to read on-site without paying anything; and both sought to create appealing spaces in a city still recovering from the First World War.[4] This attention to creature-comforts was on display when, just a week after opening, Beach wrote to her mother, “you needn’t be afraid of my freezing or anything—the little stove filled with ARC coal heats the place till the guests and myself are fairly red in the face” (Letter, in Wang 143). Around the same time, a reader of the Paris Herald celebrated that, at the American Library, “at this time when coal is so expensive, there are glowing fireplaces where warmth and cheer thaw the heart” (Ward 2).[5] These shared features meant that both libraries emerged as hubs of community connection as Paris’s American population swelled in the interwar years.[6]

The most concrete distinction between the two institutions was their size. Beach described her shop—a former laundry—as “two rooms, with a glass door between them, and steps leading into the one at the back” (Shakespeare and Company 17), while the dramatically larger American Library was, in its early years, spread over three floors of a “beautiful old hotel” (“Some Facts” 201). The differing scales of these physical spaces was matched by their membership numbers and holdings. In 1926, during the population peak of Paris’s American colony, the ALP claimed 4387 cardholders, while the Shakespeare and Company Project (SCP) records only 249 members at Beach’s library (fig. 1).[7] That year, the ALP reported 37,071 circulating works, while, in contrast, the SCP data has identified around 6,000 titles available for loan during Shakespeare and Company’s twenty-plus-year existence (1919–1941).[8] While Shakespeare and Company, thanks to its intimate connections to the era’s most famous writers, is the Paris-American library that has attracted the most attention, these differences in size and scale are reminders that Beach’s library represented just a fraction of the city’s exchange of English-language books.[9]

Who Belonged Where?

The membership rolls of the two libraries provide a site to consider their complementarity. Although the ALP was the significantly larger institution, it is Shakespeare and Company that has left the more detailed records. The SCP considers their list of the lending library’s members—totaling about 5,235 individuals between 1919 and 1941 and compiled from borrowing cards and Beach’s logbooks—“near-complete” (Kotin and Koeser, “Data Sets” 10). The ALP’s records, on the other hand, supply the names of only around ten percent of the Library’s borrowers, via their published annual reports on members and patrons (fig. 2).[10] These reports contain the names of the 300–400 individuals who paid for a formal membership at the library each year: leaving out monthly and bi-annual subscribers; students and teachers for whom a borrowing card was free; the staff of the many American organizations with company memberships; and all those who used the reading rooms without borrowing privileges.[11]

Despite the incomplete data, there is value in comparing these two institutions’ member lists. A comparison of names across the American Library and Shakespeare and Company’s membership rolls reveals that, out of over 900 members identified by the ALP in the 1920s and the more than 5,200 on the SCP’s spreadsheet, there are just thirty definite crossovers.[12] This would suggest wild differences in the institutions’ memberships, were one not aware of the partiality of the ALP information. The fact that there are any overlaps means we can surmise that a fuller picture of the ALP would reveal many more people who borrowed from both libraries. This conjecture, reduced to the numeric, suggests that if just ten percent of known names from the American Library yield thirty overlaps, we might expect closer to 300 repeated names if the ALP’s full list of borrowers was available.

The short list of coinciding members challenges the idea that Paris’s American community generally regarded the libraries as rivals. Two names that appear on both lists belong to members of the ALP’s governing bodies: the Comtesse de Chambrun—née Clara Eleanor Longworth in Cincinnati, Ohio—was a Shakespeare and Company member in 1923 and 1924, as well as being one of the ALP’s most stalwart supporters from its inception; and George Fleurot, who belonged to Beach’s library in 1926, was a member of the ALP’s Committee on Ways and Means in 1924. If belonging to one library was a blow to the other, it seems unlikely there would be this reciprocity among the ALP’s leaders.

There are insights to be gathered from the absences in the ALP’s records. Take, for instance, the case of Ernest Hemingway, who does not appear on the American Library’s available membership lists and was known to be an early, passionate supporter of Shakespeare and Company. If one subscribes to the idea that the libraries were rivals, one might assume that Hemingway aligned himself with Beach over the ALP. Yet Hemingway was friends with the ALP’s director W. Dawson Johnston, asserting in 1925 that “Dr Johnston is a priceless bird and his wife is the genuwind [sic]. . . . We are very fond of them” (Letters 2: 227). Hemingway also demonstrated his support for the ALP by publishing two book reviews in the American Library’s publications (Review, Chicago Tribune; Review, Ex Libris). If one of interwar Paris’s most storied writers is an unrecorded supporter of the ALP, there are likely many other familiar names absent from the ALP’s records.[13]

“DAMN the right bank pigs” Ezra Pound wrote to Beach when he read a report in the Paris Herald that the American Library had banned an issue of H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury (quoted in Fitch 62).[14] This response reflects a common desire to imagine the divide between the libraries along geographic lines—with the artistic Left Bank patronizing Beach, and the prosaic Right Bank visiting the ALP.[15] This is a distinction between the libraries’ members that is, to an extent, supported by the data. The SCP’s analysis of Beach’s membership shows that “the majority of the members of the Shakespeare and Company lending library lived on the Left Bank,” while in 1926 the ALP reported that only “3 per cent” of members lived “on the south [Left] side of the river” (McCarthy and de Sá Pereira; ALP Year Book 1926 29). But since Beach’s library was located on the Left Bank, and the ALP on the Right, might this simply be a matter of convenience for patrons, rather than a declaration of loyalty? The idea of an artistic/prosaic divide that conformed to geographic lines is challenged by the SCP’s data, which shows Right Bank addresses for members including F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Paul Valéry, Archibald and Ada MacLeish, and even James Joyce. The ability to access Anglophone literature from various places in the city likely made both libraries attractive to readers from across Paris (McCarthy and de Sá Pereira).

What Did People Read?

In addition to comparing the two libraries’ memberships, we can look at the data to provide a glimpse of members’ borrowing habits. The SCP has produced a dataset from the borrowing records for Beach’s lending library, although it has limitations: Beach preserved the lending library cards of 654 members, a fraction of Shakespeare and Company’s total users (Kotin and Koeser, “Data Sets” 6). Once again, information from the ALP is even more limited: patrons’ borrowing can only be compiled from irregular, narrative reports that librarians provided to local newspapers.[16]

Yet even this partial picture provides insight into the similarities and differences between reading choices at the two libraries, and allows these Anglophone Parisians’ tastes to be contrasted with readers’ selections in the United States. In what follows, I will compare reading habits across the libraries at three moments: on or about 1922, that annus mirabilis of modernist literature; 1927, while Paris’s American colony was at its interwar peak; and 1930–31, when the effects of the Depression were beginning to be felt, and many Americans were returning to the US.

To begin with the first of these periods: the early 1920s, not long after the launch of both libraries. The most granular data for borrowing at the American Library comes from January through March of 1922, when the Library began producing weekly columns for the Paris Herald and the Paris Tribune, which featured lists of popular titles.[17] This short-lived snapshot reveals that patrons were eager to read A. S. M. Hutchinson’s If Winter Comes (1921); John Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers (1921); the final novel in John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga, To Let (1921); Lytton Strachey’s Queen Victoria (1921); Frederick O’Brien’s travelog Mystic Isles of the South Seas (1921); and H. G. Wells’s account of post-World War I diplomacy, Washington and the Hope of Peace (1922) (New York Herald, “Latest Library Additions” 2).

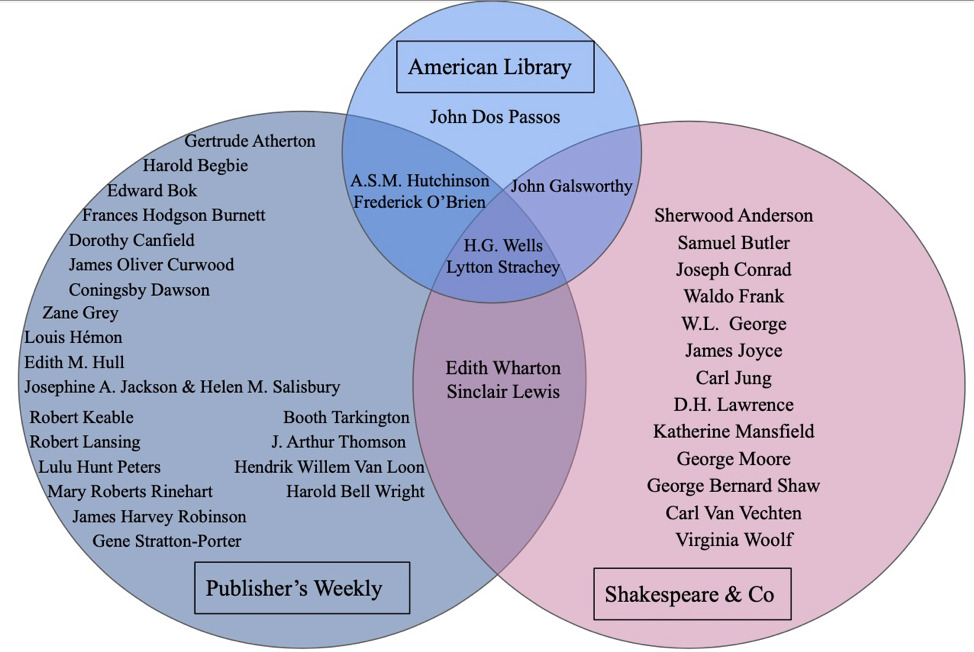

How do these titles compare to those read by Beach’s members, and to readers in the US? Some were popular across both Paris libraries—the Galsworthy, Strachey, and Wells books were borrowed repeatedly from Shakespeare and Company in 1922. Some, however, were not: the SCP records do not report copies of either Hutchinson’s or O’Brien’s books at Beach’s shop. The data for Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers is more ambiguous: Beach’s library does not have any loan events recorded until 1926, which might suggest a lack of interest among her members, or that the membership cards showing its circulation are among the many no longer extant, or that she did not acquire a copy until later. In the US, the Hutchinson, Strachey, and O’Brien books all appear on the Publisher’s Weekly bestseller lists in 1921 or 1922, but the Galsworthy, Dos Passos, and Wells do not (a different Wells work, The Outline of History [1920] is on the lists, hence his appearance on figure 3).[18] Strachey’s biography, Queen Victoria, is the only title the data shows to be popular at all three sites (fig. 3).

Many of the works on the Publisher’s Weekly lists of popular content in the US were not held by Beach’s library at all, nor were they mentioned by the ALP’s librarians: reading choices of Americans in the US clearly differed from those of visitors to the lending libraries abroad.[19] One book with a particularly notable contrast between its popularity in Paris in the early 1920s and in the US was Edith M. Hull’s romance, The Sheik (1919). Frank Luther Mott’s Golden Multitudes (1947)—which identifies bestselling books by their cumulative sales figures by 1947—names The Sheik as the only book published in the US in 1921 to have sold over a million copies, and it appears on the Publisher’s Weekly lists in both 1921 and 1922 (313).[20] However, the weekly reports on popular titles at the American Library in early 1922—when sales of The Sheik were soaring in the US—do not mention it, and only one borrow is recorded for the book at Shakespeare and Company in 1921. This single borrow, though, confounds any neat divide between modernist and middlebrow taste at the libraries: the borrower of The Sheik was none other than Gertrude Stein!

Jumping ahead to 1927, evidence shows that the preferences of readers at the two libraries in Paris had more in common with each other than with readers in the US. A headline in the Paris Herald reflecting on 1927’s borrowing habits declared “Love Story Passé; Paris’s Americans Demand Modern Detective Yarn,” naming British writers J. S. Fletcher, E. Phillips Oppenheim, and Edgar Wallace as the ALP’s most popular mystery authors (2). Beach’s records, too, show that these writers were popular: she held twenty titles by Fletcher, twelve by Oppenheim, and ten by Wallace. But in the late 1920s, none of these authors appeared on the Publisher’s Weekly lists, nor among Mott’s top cumulative sales figures. Detective fiction simply did not dominate the US bestseller lists of the period. And it wasn’t only detective fiction indicating that borrowers in Paris had preferences distinct from those in the US: the Herald article also names Theodore Dreiser’s realist An American Tragedy (1925) and Rosamond Lehmann’s romance Dusty Answer (1927) as popular at the library (“Love Story Passé” 2). Both books were frequently borrowed from Shakespeare and Company as well that year, yet neither appeared on American bestseller lists.

The third snapshot of borrowers’ tastes—the early 1930s—supplies additional evidence of a division between readers in Paris and those in the US. In 1930, ALP librarian Margaret Carmichael told the Herald that “American, French and English residents preferred books by Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis, with Joseph Hergesheimer running a close fourth…the library finds the following contemporary authors enjoy wide circulation: Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Margaret Deland, Hugh Walpole, Katherine Mansfield, and Edna Ferber” (“U. S. Tourists Scorn Fiction” 5). All of these authors were popular at Beach’s bookshop, with her library holding multiple titles by each of them. But in the US, there is no such overlap. Of these ten names, half (Lewis, Walpole, Wharton, Cather, and Ferber) produced American best sellers, while the other five (Mansfield, Dreiser, Anderson, Hergesheimer, and Deland) never made appearances on the Publisher’s Weekly lists.

As discussed, the differences between Shakespeare and Company and the ALP in the popular narrative of the two libraries are framed largely through their associations with modernist and middlebrow literature, respectively. Therefore, I would like to say a bit more about what this article’s sources reveal on this front.[21] In her memoir, Beach explained that she opened her library in Paris because “our moderns . . . were luxuries the French and my Left Bankers were not able to afford” (Shakespeare and Company 21). The ALP, on the other hand, professed no such commitment to modern literature, and the data from the two libraries’ earliest years reflects these different priorities. Figure 3, the diagram of popular authors in 1921 and 1922, includes Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, Michael Arlen, Richard Aldington, and Carl Van Vechten at Beach’s bookshop—all of whom are absent from the other lists during this period. But as the 1920s progressed, Shakespeare and Company’s distinction as the sole source for modernist texts in English diminishes: a 1931 Paris Herald headline about the ALP declared: “Readers Here Have ‘Highbrow’ Tastes” (5). As proof, the article cites popular titles that include Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928) and Gertrude Stein’s Lucy Church Amiably (1930). Joyce—already, of course, popular at Beach’s bookshop—is also included on this 1931 list from the ALP. Although the two libraries may have started by appealing to different clienteles, it appears that, by the 1930s, readers at both libraries in Paris had catholic reading habits across genres, with signs of more overlap between readers in Paris than with their compatriots at home.

Conclusion

In The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) the fictionalized Toklas reports that she and Stein first joined Beach’s library because “there was the American Library which supplied us a little, but Gertrude Stein wanted more. We investigated and we found Sylvia Beach” (195). I would like to linger on this word “more,” which seems aberrant when describing a lending library with a fraction of the members and the holdings of the ALP. What if, instead of telling a story of the libraries vying for Toklas’s and Stein’s favor, we read this “more” to suggest the two libraries complemented each other, and that, together, they provided more reading opportunities to Paris’s interwar Americans? The importance of Shakespeare and Company to the story of modernist literature and expatriate Paris is already established. Understanding Beach’s library in relation to the ALP can broaden our understanding of the era, and what these individual institutions gave to it.

How does the data from the SCP and the ALP help us better understand the relationship between the two libraries? Alongside contextual historical materials, including newspapers and reports on US book sales, it complicates neat divisions between the two libraries and diminishes an unexamined narrative of rivalry. We see overlaps in the two libraries’ membership lists, and evidence of patrons who lent their ardent support to both institutions. The data suggests that while, upon founding, Beach’s library may have offered more modernist literature than the ALP, as time progressed members at both libraries became interested in popular and avant-garde writing, and that readers in Paris had more in common with each other than with readers in the US. The data confirms that while the Left and Right bank affiliations of the two libraries have geographic merit, they lack a clear aesthetic divide. Let us stop telling a story of these two libraries as rivals, and instead better understand them as complementary nodes in the network of Paris’s interwar Anglophone community.

Acknowledgements

This research was completed with the support of the Ernest Hemingway Society and the Lewis-Reynolds-Smith Founders Fellowship. Immense gratitude is also due to Abigail Altman of the American Library in Paris.

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KYZGKH

For Shakespeare and Company project datasets, see Kotin et al., Dataset. The ALP began producing Year Books to report on the previous year’s finances and activities in 1921. See “Annual Reports.”

Among the many texts to develop the ideas of modernist collaboration and networks are Davidson; Gifford; and ed. Southworth.

The American Library launched as part of the Library War Service, funded by the American Library Association, in 1918, and transitioned to an independent institution in 1920. See Bone and Thompson.

For more on joining Beach’s library, see Kotin, “Becoming a Member.” ALP membership costs are available in ALP Year Book 1923, 36.

I have written about the ALP’s interior and its history in “‘Essentially an American Institution’” (207–225).

At its peak in the late 1920s, there were at least 40,000 Americans living in Paris. Green discusses the difficulty of obtaining an accurate count, given the transience of the community and discrepancies between American and French government records (Other Americans 17).

Based on the Year Book data, 1925 and 1926 represent dramatic highs in the number of those borrowing books from the ALP, although it is unclear how consistent the library’s methods of tallying users were across years. The Year Book report 3697 cardholders in 1921, 3500 in 1922, 2270 in 1923, 2781 in 1924, 4678 in 1925, 4387 in 1926, somewhere between 1825 and 3110 borrowers in 1927, up to 3404 members in 1928, and 3402 for 1929 (see ALP Year Book 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930*); Kotin and Koeser, “Data Sets” 4.

The ALP figure comes from ALP Year Book 1927, 42.

In addition to many personal lending libraries—such as those of Nancy Cunard and Ada “Bricktop” Smith—the other prominent Anglophone bookshops and lending libraries in the city during the period were Galignani Library, Brentano’s, and W. H. Smith and Son.

For example, the ALP claimed as many as 3404 members in 1928 but named only 391 of them in the Year Book; see ALP Year Book 1929, 27, 44, 79–86.

In 1922, memberships were priced at the following rates: to be a “Patron,” one had to give at least Fr5,000; to be a “Life Member,” Fr2000; for an annual membership, a one-time Fr100 fee, plus an additional Fr100 per year. See ALP Year Book 1922, 29.

About twice that number of names lack enough specificity to determine if they correspond.

Famed artists and writers whose names do appear on the ALP’s membership roles include Stein; Edith Wharton, a longtime supporter and sometime board member at the ALP; the sculptor Janet Scudder; the writer John Peale Bishop; the novelist Louis Bromfield; the French essayist and critic Charles du Bos; and the arts patron Otto Kahn.

Pound is responding to a report in the Herald from April 27, 1926 that said that the issue containing Mencken’s censored “Hatrack” had been banned by the library. This report was retracted in the following day’s paper, with the director, Burton Stevenson, clarifying that it was simply being kept at the magazine room’s desk to prevent theft (“‘American Mercury’”).

Benstock explores this division between the Seine’s banks extensively; see especially Women 34–35.

Although individual titles are absent from the ALP’s year books, beginning in 1926 they provide numeric details on borrowing in the following genre categories: general, philosophy/religion, sociology, literature, history, travel, biography, language, science, useful arts, fine arts, fiction, rental, periodicals, juvenile. See ALP Year Book 1926, 29–30.

These columns continued through the 1920s and into the 1930s, but the lists of popular books for the week were short-lived.

Publisher’s Weekly best seller data comes from Hackett.

The bestselling books not mentioned by the ALP nor held by Shakespeare and Company: Mary Roberts Rinehart’s A Poor Wise Man (1920); Gene Stratton’s Her Father’s Daughter (1921); Gertrude Atherton’s The Sisters-in-Law (1921); Coningsby Dawson’s The Kingdom Round the Corner (1921); and Zane Grey’s The Mysterious Rider (1920). See Hackett 43.

The Sheik was first published in the UK in 1919, and in the US in 1921.

For the purposes of this piece, I am more interested in whether an author’s reputation in contemporary scholarship groups them into one of these categories than I am in formal definitions of modernism and the middlebrow. For more on modernism and the middlebrow, see Middlebrow Moderns: Popular American Women Writers of the 1920s, ed. Lisa Botshon and Meredith Goldsmith (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003); Lise Jaillant, Modernism, Middlebrow and the Literary Canon: The Modern Library Series, 1917–1955 (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2014).