Although celebrated for its support of male modernists—James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound—Shakespeare and Company was run by and mostly for women. Sylvia Beach opened the bookshop and lending library in 1919, inspired by her romantic partner, Adrienne Monnier, who owned the French-language bookshop and lending library, La maison des amis des livres.[1] Beach’s assistants were all women: Myrsine Moschos, Margaret Newitt, Eleanor Oldenberger, Paulette Lévy, Ruth Camp—to name only a few. The majority of the lending library’s members were also women: writers, teachers, students, governesses, aristocrats, artists, tourists, homemakers. Finally, women were responsible for the majority of the lending library’s circulation—due, in part, to the borrowing activity of two voracious readers, Alice M. Killen and France Emma Raphaël.

We wrote this article to better understand the relationship between gender and taste at Shakespeare and Company. Inspired by Melanie Micir’s description of Beach’s record keeping as a “queer feminist modernist practice,” we wanted to learn more about the composition of the lending library’s holdings and the borrowing practices of its members (88).[2] What percentage of the lending library’s holdings were by women? How likely were men to read books by women, and vice versa? Did men and women prefer different authors? The datasets from the Shakespeare and Company Project promised to help address these questions.

As we conducted our research, we remained alert to the limitations of our inquiry. We were wary of overstating the importance of gender—as if a single attribute could explain the reading preferences of an entire community. We were also wary of essentializing the categories “man” and “woman”—as if a person must be one or the other. Shakespeare and Company was a community of women, but it was also a community that challenged and transformed gender norms. Finally, we were wary of misgendering individuals. The Shakespeare and Company Project datasets use first names and titles from Beach’s records to identify the gender of lending library members. The Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) identifies the gender of published writers.[3] Neither resource is perfect. With these limitations front and center, we analyzed the datasets and created an additional one of our own.

Three findings emerged from our research. First, we discovered that the vast majority of books in the library were by men. Second, we learned that women were almost twice as likely as men to borrow books by women. These findings led to a third. The female authors with the highest ratio of male to female readers constituted a recognizable canon: Agatha Christie, Emily Dickinson, Gertrude Stein, Marianne Moore. In contrast, the female authors with the highest ratio of female to male readers were much less familiar: Margaret Kennedy, E. M. Delafield, Rebecca West, Elizabeth von Arnim, Mary Borden, Kay Boyle. This third finding was startling and led to additional questions. Did the preferences of men predict or even determine the nineteenth- and twentieth-century canon, including the recovery projects that redefined it in the 1970s and 1980s? Could we use the preferences of the women at Shakespeare and Company to identify a counterfactual canon of modernism? At this stage of our research, the finding is closer to a provocation than an argument, but it challenges assumptions about the formation and reproduction of the modernist canon, and presents a new agenda for modernist studies: how would modernist studies change if we began talking about a “von Arnim Era”?

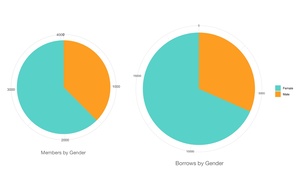

To begin our research, we used the Shakespeare and Company Project datasets to reveal the gender demographics of the lending library membership. The datasets identify the gender of 4,039 members—sixty-two percent of whom were women (Kotin et al., “Lending Library Members”).[4] Of the 20,518 borrows by members with identified genders, 16,022 were by women—over seventy percent (fig. 1). These numbers more-or-less match the findings of Joshua Kotin and Rebecca Sutton Koeser in their article about the most popular books at Shakespeare and Company, which used a previous version of the datasets.

To discover the gender distribution of the authors of the lending library holdings, we had to create our own dataset. We reconciled the author names in the Shakespeare and Company Project datasets with gender information from VIAF. We limited our analysis to single-authored books. This dataset ultimately included 5,075 books—79.5 percent of which were written by men. As we considered this number, we worried about the influence of canonical literature. When Beach began to collect books for the lending library, she visited bookshops around Paris and bought all the inexpensive English-language books she could find—mostly canonical literature. She collected 1,012 books in all, only 107 of which were by women, eleven percent (“Volumes”).[5] To mitigate the influence of these purchases—and the gender-imbalance of canonical literature in general—we identified a subset of contemporary literature: 3,684 books published between 1919 and 1941. These holdings were still dominated by men, although to a slightly lesser extent: seventy-five percent (fig. 2).

To contextualize these percentages, we examined the holdings of Princeton University Library. Princeton holds 6,757 novels published between 1919 and 1941: seventy percent were written by men and nineteen percent by women. (The authors of the remaining novels either do not have VIAF numbers or gender information in VIAF.) We also analyzed other genres—poetry, philosophy, history, psychology—and the percentages held.[6] For additional context, we compared the most popular books at Shakespeare and Company to bestseller lists from the period. Six of the top ten most frequently borrowed books at Shakespeare and Company were by men—sixty percent (Kotin and Koeser). The percentage corresponds to the percentage of books by men on the Publishers Weekly bestseller lists between 1919 and 1941. On those lists, 363 out of 549 books—sixty-six percent—were written by men.[7] By these measures, the gender demographics of the Shakespeare and Company lending library holdings were fairly conventional.[8]

Next, we focused on the borrowing practices of lending library members. How often did men read books by women? The answer is dismaying but unsurprising: not very often. Of the total borrows by men, only fifteen percent were books written by women.[9] In contrast, thirty percent of the borrows by women were of women authors—a percentage that corresponds to the gender distribution of the lending library’s holdings. Men, it seems, actively avoided reading books by women, whereas women simply didn’t seek out such books.

What about the kinds of books that men and women read? The top five female authors are the same for both men and women, although women seem to have preferred literary fiction to crime fiction, while men valued the genres equally. Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Christie are popular among both groups. Divergences begin to appear further down the lists. While men were reading Pearl S. Buck, Stein, Edith Sitwell, and George Eliot, women were reading Kennedy, Boyle, and Delafield (table 1).

To push our analysis further, we identified the most polarizing authors at Shakespeare and Company. Since the total number of borrows by women is more than twice that of men, we first had to find a fair way to compare borrowing preferences. For each author, we calculated a percentage based on the total borrows by each demographic group. For example, the 252 borrows of Woolf by women represent six percent of the total borrows by women, while the forty-three borrows of Woolf by men represent 5.2 percent of the total borrows by men. We then calculated the difference between the two percentages—the delta score—for each author. The results reveal the most polarizing authors (tables 2 and 3).

To represent these results in a visual format, we provide a chart showing the most polarizing authors. (Rebecca Sutton Koeser designed and implemented the chart.) The figure below indicates the total borrow percentage of each author for both women (on the left, in orange) and men (on the right, in turquoise). The black line traces the delta between the borrow percentages. The authors most preferred by women have positive deltas, while the authors most preferred by men have negative deltas (fig. 3).

What can we learn from these results? First, members of the lending library agreed on which men to read, but not which women. The authors with the highest deltas are almost always women. Except for Henry James (preferred by men) and Hugh Walpole (preferred by women), all the remaining authors in the top ten for both groups are women. (Interestingly, Shakespeare has a delta score near zero.) Second, male members, unlike female members, overwhelmingly preferred crime writers and women authors who eventually—belatedly—became canonical: George Eliot, Dickinson, Moore, Stein. (Christie is likely the most canonical author of genre fiction.) The only canonical female author on the list of authors preferred by women is Woolf—and she was also popular among men, as the top ten lists indicate.

These results suggest that the preferences of men at Shakespeare and Company not only predicted (and perhaps helped to determine) the canon of nineteenth and twentieth-century literature, but the recovery projects that redefined it as well. At the same time, the results offer a way to see (and read) beyond this canon: to identify a counterfactual canon that reflects the actual preferences of women readers and the influence of women authors. This counterfactual canon has the potential to inspire new recovery projects and histories of modernism.

What if we were to start reading Kennedy, Delafield, West, von Arnim, Boyle, and Borden alongside Joyce, Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, and Ernest Hemingway? How would this new canon change our understanding of modernism? What would we learn about recovery projects and their imbrication in long histories of power and oppression? How might such a canon lead to new accounts of artistic innovation?

Some accounts are already there to discover. A recent special issue of the journal Women highlights von Arnim’s invention of a new kind of “hybrid writing, which moves deftly between outright social satire, the diary form, the country-house novel, the (uneasy) romance and, occasionally, the Gothic” (Maddison et al. 3–4). The issue also describes her experiments in “autoeroticism” and her “proto-feminist . . . portrayal of women’s experience” that is at once “radical” and “pessimistic about possibilities for change” (O’Connell 22; Turner 56). Discussing Borden’s novels, Steven Biel and Lauren Kaminsky argue that her “experiments with anonymity and interchangeability—unlike more canonical modernist forays into interiority and individuation—make the Great War seem new and razor-sharp.” Writing about Boyle, Julie Goodspeed-Chadwick identifies her creation of a “feminist avant-garde” (52). What other innovations has modernist studies missed? More important: what innovations might modernist studies now identify? This is one of the most vital aspects of quantitative approaches to literary study: the ability to identify new questions and thus new research programs—programs that evade the assumptions that define established fields of study.

Acknowledgements

For feedback on earlier drafts of this article, we thank: Rachel Applebaum, Theo Davis, Yoon Sun Lee, Eli Mandel, Gage McWeeny, John Plotz, Kelly Mee Rich, Robert Spoo, and, especially, Rebecca Sutton Koeser. For the data and code used in this article: https://github.com/fed-ka/CFC-Paper.

Data repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JOKRHF

“Shakespeare and Company was built on Sylvia’s connections with other women,” Caitlin O’Keefe contends; “Her mother, Eleanor, wired Sylvia money from her savings to start her business; Monnier helped Sylvia find a location for the shop, and then helped her build her base of French readers” (O’Keefe, “Secret Feminist History”).

O’Keefe makes a similar claim, arguing that Shakespeare and Company fused Beach’s “literary and feminist visions” (O’Keefe, “Secret Feminist History”).

For a discussion of how and why the Shakespeare and Company Project identifies the gender of lending library members, see Budak, “Representing Gender.”

The dataset does not identify the gender of 1,196 lending library members; accordingly we excluded these members in our analysis. One lending library member—Claude Cahun—is identified as non-binary. For a discussion of the incompleteness of Shakespeare and Company Project data, see Koeser and LeBlanc, “Missing Data, Speculative Reading,” in this special feature.

Of the 1,012 books, 844 are single-author works by men and 107 are single-author works by women. The remaining sixty-one books are periodicals, edited collections, or co-authored volumes. We thank Eli Mandel for creating a spreadsheet with these books.

We thank Peter M. Green for supplying data from Princeton University Library. For a discussion of the gender distribution of the authors of books held by the Library of Congress, and on Amazon and Goodreads, see Ekstrand and Kluver, “Exploring Author Gender,” p. 381.

See “Publishers Weekly Lists.” Wikipedia cites Hackett and Burke, 80 Years of Bestsellers.

By other measures, the holdings were unconventional: the lending library stocked important, controversial books by women—from Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1926) to Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood (1936), and from Marie Stopes’s Married Love, or Love in Marriage (1918) to Margaret Sanger’s My Fight for Birth Control (1931).

Sieghart analyzes the numbers today: “For the top 10 bestselling female authors,” she writes, “only 19% of their readers are men.” See Sieghart, “Why.”