Booksellers speak through the books they sell, lend, or promote.

After World War II, Sylvia Beach officially retired from the profession of bookselling. Having closed the doors of Shakespeare and Company in 1941 under duress during the German Occupation, she never reopened her bookshop. Entering her sixties in the post-war years, she returned to live in the apartment above where her bookshop had been. Surrounded by her enormous archive, she continued to lend, give away, translate, and promote books and authors. Although she was no longer officially a bookseller, she continued to speak through books. In what follows, I trace the story of one of these books, the last one she is known to have shared.

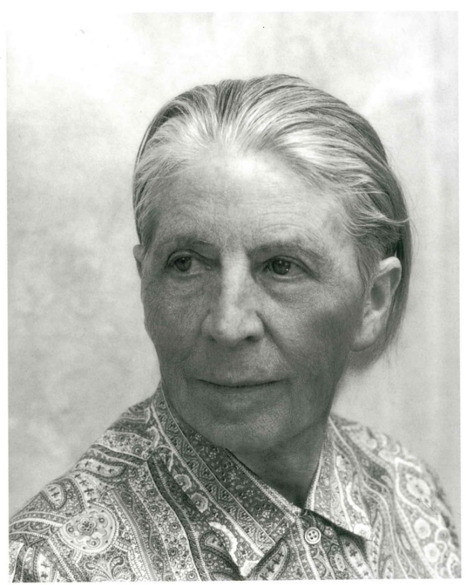

According to Beach’s records made available by the Shakespeare and Company Project, the last book she gave away was on June 28, 1962, just three months before her death. The recipient was the French writer and intellectual Jean-Dominique Rey (1926–2016), and the book was The Heart to Artemis (1962), the newly released memoir by one of Beach’s closest friends, the English writer Bryher (1894-1983) (fig. 1). Novelist, arts activist, and life partner of the American poet H.D., Bryher had been a long-time supporter of Shakespeare and Company. She was extraordinarily wealthy, the child of a shipping magnate, and she used her money to support a number of artistic and political causes. She had been instrumental in keeping Shakespeare and Company afloat during the lean years of the 1930s: in the autumn of 1935, for instance, she donated 6500 francs to help the shop’s doors stay open (Fitch 356).

Beach had been lending Bryher’s books since 1922, when records show that a copy of Bryher’s first novel, Development (1920), was returned by France Emma Raphaël. Development was Bryher’s fictionalized account of her own coddled but claustrophobic upbringing in Victorian and Edwardian England. The book included both a damning critique of the English boarding school system and an autobiographical protagonist who longs to be a sailor and regrets having been born a girl. Bryher was proud to recall that W. B. Yeats had found the novel worthwhile: she writes that he “asked me if I had written Development. . . . He said that he had also felt the educational system to be wrong and hoped that I was working on another book” (Artemis 230–232).

Beach was a champion of Bryher’s writing. Together with Adrienne Monnier, she had arranged for Bryher’s Beowulf, the story of a British tea shop during the Blitz, to be translated into French and published in the Mercure de France in 1948. The translation appeared even before the English version was published by Pantheon in 1956. Now, by giving a copy of Bryher’s memoir to a young French intellectual, she was passing on to the next generation an account of her circle that affirmed the genius and the contributions of its women, and especially its queer women.

Sylvia Beach’s careful legacy-building has not gone unnoticed. In The Passion Projects: Modernist Women, Intimate Archives, Unfinished Lives (2019), Melanie Micir considers Beach’s writing, exhibitions, and cataloging of Joyce manuscripts as acts of “curation,” rather than creation, and suggests that such acts were typical of those she calls “disenfranchised” modernist women like Beach, Alice B. Toklas, and others (85). To this list of curatorial activities, I would add Beach’s continued circulation of books, even after she closed her bookshop and lending library.

Beach’s memoir, Shakespeare and Company (1959), had appeared three years before Bryher’s The Heart to Artemis, and had provided a charming, sunny tour through nineteen-twenties Paris. Its cheerful affect rarely wavers. Still, nestled among the feel-good anecdotes are what Micir identifies as some “small but insistent notes” about the women who were subtly but surely being left out of the modernist canon, from Bryher to Gertrude Stein to Djuna Barnes to Mary Butts (Passion Projects 88). Beach’s memoir includes these writers alongside Joyce, Hemingway, and the other familiar male modernists, and pays homage to the woman who had inspired her and been her life partner, Adrienne Monnier, who founded and operated La Maison des Amis des Livres, the French bookshop across the street from Shakespeare and Company. There is a subtle but notable feminism in these inclusions.

Bryher’s memoir, on the other hand, was an avenging work, as its title invoking Artemis the huntress suggests (fig. 2). Bryher had been outraged by her depiction in Robert McAlmon’s interwar Paris memoir, Being Geniuses Together (1938). McAlmon, the American writer who drank away his talent but somewhat redeemed his reputation as the founder of Contact Editions, had been Bryher’s husband in the 1920s. At that time, he was running Contact out of Shakespeare and Company. Funded by Bryher, Contact had published Hemingway, Stein, Bryher, H.D., and other key modernists. Although the spitefulness of Being Geniuses Together makes for a juicy read from an historical distance, the memoir had bruised feelings when it first appeared. Published after Bryher and McAlmon had divorced, the book depicts Bryher as neglectful, self-absorbed, and lacking emotional intelligence.

In The Heart to Artemis, Bryher rewrites the story of these years from her own point of view, giving readers an understanding of how her passionate love for H.D. shaped her life and helped her defy her parents. She also argues that McAlmon had agreed to a marriage of convenience, and discusses her support for the Left Bank’s women of genius and her work helping refugees escape from Nazi-occupied Europe. The Heart to Artemis contains an account of Ezra Pound’s unwelcome advances: in a disconcerting scene, he puts an arm around Bryher and kisses her on the cheek while she “wondered what in the world I was supposed to do and decided to gaze at him abstractly and in silence.” Her unresponsiveness puts him off and he awkwardly shifts to other appetites, asking, “Have you no chocolates?” (Artemis 227).

The Heart to Artemis also presents a passionate celebration of Monnier, which functions as a defense against her characterization in The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams (1951). Bryher felt deeply betrayed by Williams, and in defending Monnier, she was also defending her old friend, Beach. Bryher describes how her expatriate circle had tried to help Williams get licensed to practice medicine in France, and he had “repaid this help in his Autobiography by making a number of inaccurate and derogatory statements about myself and my friends” (258). Feeling protective of Beach, Bryher objected to Williams’s homophobic depiction of Monnier:

Adrienne Monnier, a woman completely unlike Sylvia, very French, very solid, whose earthy appetites, from what she told us, made her seem to stand up to her knees in heavy loam, came in from across the street to make our acquaintance. . . . She enjoyed the thought, she said, of pigs screaming as they were being slaughtered, a contempt for the animal—a woman towards whom it was strange to see the mannishly dressed Sylvia so violently drawn. Adrienne gave no quarter to any man. Once, when Bob [Robert McAlmon] in a taxi had taken her in his arms and kissed her, she had sunk her teeth into his lips so that he expected to have a piece torn out before she released him. (Williams 193)

Bryher, in contrast, described Monnier as being “as near a saint as anyone whom I have known” (Artemis 258). Bryher also reports that her lawyers had to dissuade her from suing Williams, and that she had come to regret being dissuaded! She ends the section on Williams by reminding readers of the high stakes of their current moment, one in which unreliable anecdotes about the interwar years were at risk of being inscribed as history: “All the survivors from the [Latin] Quarter should have joined together to refute his charges in open court. There is the danger otherwise that future historians of the period may believe them after we are dead” (258).

Although Beach would likely have celebrated and circulated Bryher’s work no matter what, the section of The Heart to Artemis that pays tribute to Monnier gave Beach a particularly compelling reason to pass along the book, especially to Rey who was proving to be a tastemaker for the next generation. When Monnier died in 1955, she was the subject of a special issue of the Mercure de France that celebrated her contributions as bookseller, writer, and cultural force. Beach and Bryher wanted to do more to secure Monnier’s place in the literary history of the period. (In 1964, Violette Leduc’s La Bâtarde would contain another unflattering portrait of Monnier—but Beach did not live to see it.)

In addition to championing Monnier, Bryher’s narrative also gives the male modernists shorter shrift than Beach’s memoir. In their place, she provides readers with effusive appreciations of various literary women of the Left Bank, including an extended description of a day on which she and McAlmon ran into Gertrude Stein on a small Paris street, and a vision of Stein driving “off in her famous Ford, a jolly little dinosaur riding down the sands of time” (249).

But Bryher saved her greatest affection for Beach and Monnier and their facing bookshops and lending libraries on the rue de l’Odéon:

There was only one street in Paris for me, the rue de l’Odéon. . . . It meant naturally Sylvia and Adrienne and the happy hours that I spent in their libraries. . . . We changed, the city altered, but after an absence we always found Sylvia waiting for us, her arms full of new books, and often a writer whom we wanted to meet, standing beside her in the corner. . . .

Number seven, on the opposite side of the rue de l’Odéon, was also a cave full of treasures. . . . I see Adrienne coming towards me as I open the door of number seven, with her arms full of yellow, paper-covered books. . . . She taught us with a humility born from great pride, not in her own gifts though this would have been perfectly legitimate, but because we were all privileged to put vision above ignorance.

In her own home it is the delicious smells that I remember, herbs, a chicken roasting, the polish on the wood, these and the murmur of talk. I met Romains there and Michaux later, but this belongs to the thirties, Schlumberger, Prévost, and Chamson. It was a unique experience, first to eat the dinner because she cooked better than anyone whom I have ever known, and then to listen to the conversation of some of the finest minds in France. . . .

I took Adrienne’s kindness too much for granted and lost the chance to learn much of what she would willingly have taught me. She knew me inside out. . . .When the time came she showed us how to die and hardly a day passes now when I do not miss her. (246–248)

Rey was an appropriate person to whom to pass along this testimony. He was a connector of circles, an enthusiast, and a curator, like Beach herself. As a descendent of the Impressionist painter Henri Rouart, he had a privileged start in life. Serious childhood illness deepened his appreciation for art and literature. For a time, he had studied poetry with Paul Valéry at the Collège de France, an affiliation that aligned him with Monnier’s circle; he had also been a student of architecture (his father’s profession) at l’École des Beaux-Arts. He was a sometime-Surrealist (having crossed paths with the group in the 1940s) and an avid moviegoer who frequented Paris’s post-war ciné-clubs. After World War II, he became a prominent member of the generation of the New Wave and the New Novel, and, increasingly, of those moving beyond existentialism into structuralist and post-structuralist thought. In 1953, he married the photographer (and beekeeper) Christiane Meurisse and they had two daughters.

By the time that Beach gave Rey the memoir, he had succeeded in transforming himself from dilettante to cultural influencer. After a youth of multiple enthusiasms, toggling between the art world where he was a pedigreed insider to the literary world where he was a wide-eyed aspirant, Rey, in his mid-thirties, had found his niche as an editor (fig. 3). At the publishing house Plon, he had helped shepherd Michel Foucault’s first book, Histoire de la folie (The History of Madness), into print in 1961. The following year, he joined Éditions Mazenod as an art editor and befriended the artist and writer Henri Michaux, whose A Barbarian in Asia (first published as Un barbare en Asie in 1933) Beach translated in 1949. Michaux’s friendship helped encourage Rey to follow his interests in Eastern religions and mysticism.

Beach gave Rey a copy of The Heart to Artemis on June 28, 1962, just a few months before she died in early October in her Paris apartment above where Shakespeare and Company had once been. Rey would go on to a thirty-year tenure at Mazenod, producing numerous monographs on art, novels, and studies of literature. He would go to Argentina to research a book on Guillermo Roux and meet Jorge Luis Borges. He would publish articles in George Bataille’s journal Critique, and mingle with Claude Lévi-Strauss. Rey’s career spanned many decades: later in life he co-founded a Surrealist journal, Supérieur Inconnu (1995–2001), curated an exhibition on his ancestor Henri Rouart, and wrote a book about Michaux. As a connector of generations, movements, and disciplines, he exerted a kind of influence that was similar to Beach’s own. Perhaps it was Rey’s potential to carry on Monnier’s intellectual tradition that most inclined Beach to give him Bryher’s book.

In their later years, many of the women of modernism saw themselves being written out of the story, or consigned to background roles. By ending her career as a distributor of books by sharing a copy of Bryher’s account of modernist Paris, Beach expressed her desire to be remembered, and for her circle of queer women to be remembered, as seen through their own eyes (fig. 4).